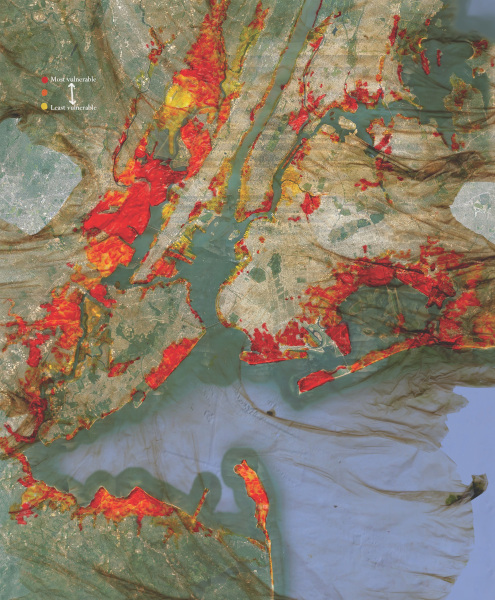

Mega-Cities Face Peril as Climate Change Intensifies

Like people, cities demonstrate their essential character when responding to a crisis. As a collection of islands and one-time swamps where the Hudson and East Rivers meet the Atlantic Ocean, New York was reminded of its basic geography in 2012, when Hurricane Sandy’s catastrophic surge brought an extra three meters (10 feet) of seawater into the estuary. Initially, Sandy was thought to be a rare event that occurs only every seven hundred to one thousand years.

But researchers at Columbia University found that the return period for a Sandy-size storm is just 103. With the one meter of sea-level rise predicted by later this century, such inundations may occur as often as every twenty-eight years, with smaller but substantial floods interspersed. Coastal megacities are in for an especially difficult journey as seas rise and storms become more intense.

In his major post-storm speech, Mayor Michael Bloomberg noted that in 2050, one-quarter of the city’s land and 800,000 residents would be within the one-hundred-year flood zone. But instead of talking about the devastation as an opportunity to reshape the city’s shoreline to better reflect future sea levels and more frequent storm surges, he doubled down. “As New Yorkers, we cannot and will not abandon our waterfront. It’s one of our greatest assets. We must protect it, not retreat from it,” he said. He pledged $20 billion in new fortifications, promoted huge luxury developments in the flood plain like Hudson Yards, and suggested creating more infilled land beyond the city’s current shoreline.

New York’s state government took a different post-Sandy approach, buying out some homeowners in Staten Island, demolishing their houses, and not permitting any future development. A federally funded design competition, Rebuild by Design, generated half a dozen innovative projects to improve rather than merely replace what had been there before, such as oyster beds to absorb wave intensity off southern Staten Island. One of the projects, a massive sea wall around the tip of lower Manhattan, is currently under construction and will, in fact, make these neighborhoods safer and more desirable—which will then encourage more growth and higher rents. It will also refract future storm surges onto the shorelines of Brooklyn, Jersey City, and Hoboken, which are already more vulnerable than Manhattan in both topography and demography.

But funding and bureaucracy pared down and slowed their construction. “Everyone was working at cross purposes,” according to Liz Koslov, an expert on post-Sandy recovery at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Bloomberg’s successor, Bill de Blasio, took long-range planning a step further by creating a Resiliency Office to coordinate upgrades to the city’s infrastructure and zoning rules and to oversee the reduction of city emissions by 80 percent, from 2005 levels, by the year 2050. However, he shares his predecessor’s basic assumption that New York’s footprint is simply too important to question or change. So the city continues to reinforce its historic economic and development priorities, relying on modest changes to land-use policies and building codes to keep people safe. People are not demanding change, so “there is no real desire to reverse course,” says Koslov.

Some recent adaptation plans have taken a more comprehensive approach, but even these efforts aren’t solving for the long term. The Resilient Edgemere plan will spend $100 million to improve a small, neglected community on Jamaica Bay in Queens with new low-income housing and infrastructure, conversion of a few flood-prone residential blocks into a park, a voluntary home buyout program, and an earthen berm to protect against thirty inches of sea-level rise. Yet the plan acknowledges that average sea levels will be higher than this in just a few decades—not including any unusually large storms or tides. So, expensive half measures are taking the place of difficult conversations and unpopular zoning changes. “No one is building for the 500-year storm,” says Lynn Englum of Rebuild for Design.

New York does have its share of truth tellers who are trying to get the attention of politicians and the public. “Sandy may not happen again like it did,” according to J. Andrew Martin, acting chief of the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) risk-analysis branch in New York, “but there will be something very similar, and it’s not that far off.”

Klaus Jacob, of the Earth Institute at Columbia University, has warned, “Sea-level rise is the ultimate fate of the city. . . . It can adapt. [New York] can be a totally lively city without [storm] barriers. We are lucky. We have high ground within our boundaries. We just have to move together on higher ground.” A city that has grown weary of disasters could begin investing in the future now.

At the federal level, the Army Corps of Engineers, which holds national responsibility for building and maintaining flood defenses, is studying several options to protect the greater metropolitan area, including a $119 billion moveable storm barrier reaching across the Verrazano Narrows. According to environmental watchdogs, this would be a catastrophe for the region’s water quality and aquatic life, while the more modest and affordable options would provide less protection. But none of these visions address the unyielding reality of sea-level rise, which is predicted to rise one to two meters (three to six feet) this century. Through “strong local voices” make a big difference in the Corps’ ultimate decision-making process, according to Brigadier General Peter Helmlinger, there is still little public debate on how to prepare for the inevitable.

Another major federal player is the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), which sells mandatory insurance to property owners in the one-hundred-year flood zone. Its rates are only half what the market rate would be for similar insurance, which encourages overdevelopment in risky areas. And its benefits flow disproportionately to upper-income people and homes that flood repeatedly; 3 percent of the claims soak up 30 percent of the budget, and the program is in unsustainable debt. More troubling, the NFIP’s flood maps are based only on historic flood risk, not the projected risks of anthropogenic sea-level rise, so they paint too optimistic a picture of what’s to come. In 2015 FEMA developed new, more accurate maps for New York, but there was such an outcry at the more realistic projections that the city had to negotiate a compromise with the agency. The new maps show future risk, but only require insurance for people at “current risk”—data that will be out of date all too soon. Eighty percent of properties damaged by Sandy were above the one-hundred-year-flood line.

New York’s goal is zero displacement of people from a Sandy-size storm by midcentury, which city officials think they can achieve, according to Daniel Zarrilli, Mayor de Blasio’s chief climate adviser. Zarrilli places his hope in Flexible Adaptation Pathways, a planning approach that keeps more future choices open. For example, spending a little more now to build levees that can be added on to later is preferable to having to start from scratch in a flooded future.

But with 520 miles of shoreline, there is no combination of engineering works that can protect all of the city’s existing perimeter. Difficult as it is to make expensive changes before the storm strikes, New Yorkers need to get in front of future disasters. With “zero federal planning” or funding coming from Congress, Zarrilli acknowledges that New York is on its own.

This is an excerpt from The Atlas of Disappearing Places by Christina Conklin and Marina Psaros (The New Press). It’s published here with permission.

Highbrow Magazine

Image Sources:

--The New Press

--Alex Azabache (Pexels, Creative Commons)