Exploring the Significance of Ecological Art

Early in the fall of 1971, I stuffed my two big dogs into my VW Beetle and drove 80 miles an hour up the California coast under a vivid blue sky, past vast blurs of brilliant color, from San Diego to CalArts in Santa Clarita. Our trip had a dreamlike quality. Shiva, my neurotic black Belgian shepherd, and Rosa, my white German shepherd, were excited about the heady scents they inhaled through the window. We were passing fields of commercial flower farms, which have long since vanished under housing developments.

I was becoming interested in the ecological idea that the heart of a system depends on its periphery. The biological edges we were passing seemed to parallel contemporaneous discussions about social and psychological boundaries.

Ecologically, vulnerability at the edges is important for several reasons. First, the edges of any habitat are crucial to its integrity. Fragmentation can be dangerous because of its impact on ecotones, which are the subtle transitions from one nuance of habitat to another. Ecotones can be as rich in subtlety as human relationships. Ecotone microhabitats act as filters and bulwarks to support larger systems. An intact ecotone system is where animals migrate between food sources or for water, shelter, and mating. Edges are also an insurance policy to provide resilience to disruptions. Resilience allows species and peoples to sustain communities in equilibrium.

Finally, ecologists speak of biological redundancy as natural engineering to protect systems. Any edge is, in effect, a pool of many small variations on biological functions in case any species in the core habitat is threatened or weakened. These subtle complexities reinforce ecotones. That wider impact from the periphery to the heart is the rub. In our age of climate change, unless we intervene in fragmentation, nothing will be left to mitigate the disaster of maximum warming.

That day in 1971, as my dogs and I approached and then left Los Angeles behind, we traversed the futuristic concrete highway complexes that the historian and urban critic Lewis Mumford had identified as the greatest public artworks of the 20th century. We encountered scant traffic. My destination was a meeting with the artist Allan Kaprow a week before fall classes began at CalArts.

I had with me a slim black portfolio of typed-up performance scores to show Allan.

When the dogs and I pulled into the CalArts parking lot, the dogs tumbled out and set off racing over the then-empty hills surrounding the campus until I called them back to my car. My goal as I walked into the large, newly built, shiny, industrial-looking building was to ask for a job.

I never got that far.

I found my way to the office of the School of Art, where Allan was the vice chair. We sat across from each other alongside a desk and exchanged greetings. I handed him my portfolio. He quickly scanned through it. Before I had a chance to ask for a job, Allan turned his head and yelled across the room to the painter Paul Brach, then chair of the School of Art, who was standing not far away.

“I want her as my student!”

Paul smiled slightly, nodded laconically, and just like that, I began to work with Allan. I thought that was better than a teaching job. Allan became my mentor. He got me a job and a scholarship and made me his assistant the following year, when I started graduate school.

Change was in the air. The first green parties would be established in 1972 in Tasmania, Australia, and New Zealand. Despite my challenges in San Diego, I was sure that new possibilities would emerge from formal ideas based in artmaking about social dynamics, such as I had discussed with Herbert Marcuse, when I had audited classes at University of California San Diego.

Ecoart, or ecological art, as a distinct genre has evolved as a hybrid form from people like me who couldn’t accept silos. Where land artists such as Robert Smithson were using sculptural techniques to stamp their own philosophical comments on the Earth, as my father had, ecoartists are driven by the sense that the Earth desperately requires healing much more than stamping.

It was at this time that I produced Physical Education, a performance art piece that involved ritualized direction that could be enacted by performers with or without formal training. I thought Physical Education was both explicit and elegant exploration of how we manage water that included a nod to ecofeminism.

These were the exact instructions for each performer in Physical Education:

1. Take a plastic baggie and a plastic spoon. Go to a water fountain or sink in an institution. Fill the baggie half full of freshwater and seal it. Drive to the ocean. Stop four times en route. At each stop, take a teaspoon of earth and put it in the baggie with the institutional water and leave behind a teaspoon of the freshwater at each site. Reseal the baggie each time.

2. At the beach, get out of the car and find some very dry sand. Pour out the earth and water mixture into the dry sand. Walk to the water, refill the baggie half full with seawater, and seal it. Return to the car. Drive back to the original institution, stopping four times en route to leave behind a teaspoon of seawater and gather a teaspoon of earth to replace it.

3. On returning, take the baggie to a toilet. The remaining seawater and arable soil mixture are then poured down the toilet. Flush the toilet. If the spoon is plastic, discard it.

Variation: Use a special spoon to transfer the mixtures of earth and water. Keep the spoon.

Today this work still interests me, both as a study in paying attention to ecotones and as a subtle political statement. It ritualized the incremental transactions between an institution, a human, and the ecotones of transition from land to sea and back to built infrastructure. Water and the ocean were common ecofeminist iconographies. The toilet was likened to a vagina. Flushing the water down the toilet was how I saw us squandering the natural world.

Author Bio:

Aviva Rahmani is the author of Divining Chaos: The Autobiography of an Idea. She is a pioneering ecological artist who has worked at the cutting-edge of the avant-garde since she committed to her career in art at the age of 19. Rahmani is an affiliate of the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research at the University of Colorado at Boulder. She earned her Ph.D. from the University of Plymouth, U.K., and received her BFA and MFA at the California Institute of the Arts.

This is an excerpt from Divining Chaos. It’s published here with permission.

Highbrow Magazine

Images:

Portrait of the Artist Mother Egg tempera on wood 44”x36” 1979

Portrait of the Artist's Father oil on linen 36”x36” 1987

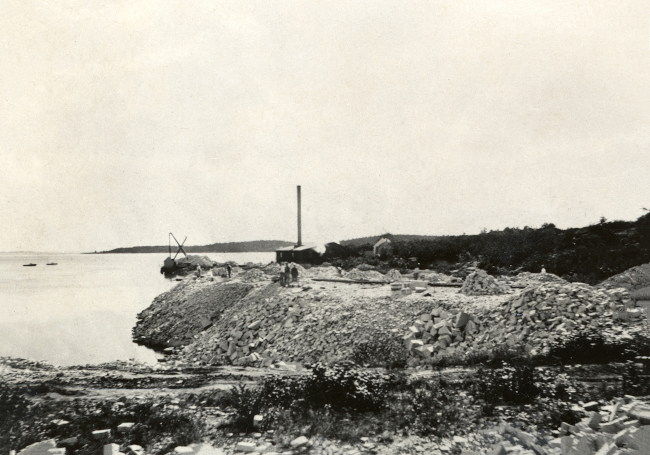

Ghost Nets site 1930 courtesy of The Vinalhaven Historical Society

Ghost Nets excavation work, photograph by Ben Magro 1997

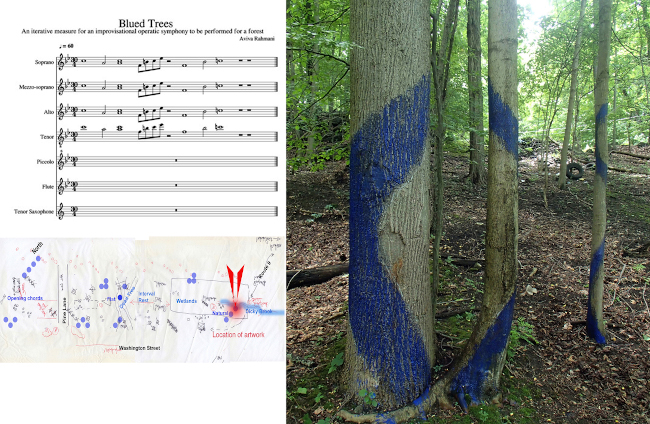

Elements for copyright of The Blued Trees Symphony 2015