James Van Der Zee: A Portrait of the Harlem Renaissance

In the 1920s and ‘30s, something extraordinary was happening in the Black neighborhood of New York City, Harlem.

This newly-minted “Renaissance” in African American culture was bursting at the seams. Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Bessie Smith, Fats Waller, and Bill “Bojangles” Robinson were blowing off the rooftops and floorboards of music halls with their music and tap dancing. And that was only the tip of the iceberg. By 1920, some 300,000 Blacks from the South had moved North, making Harlem the most popular of destinations. Somebody had to record it for prosperity.

That somebody was James Van Der Zee, a Black photographer who not only knew how to snap the picture, but turn it into a portrait of respectable, highly visible, middle-class culture. The National Gallery of Art’s current exhibition, James Van Der Zee’s Photographs: A Portrait of Harlem, illustrates in 40 images from their collection how Van der Zee managed to transform his subjects.

Celebrities such as Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. and Marcus Garvey found their way easily enough into his studio, but most of his work was of the straightforward commercial studio variety—weddings and funerals (including portraits of the dead for the grieving families), teams, clubs, shopgirls, and that burgeoning class that wanted to show off its finery. Props, costumes, and other background paraphernalia became the norm.

Portrait of a Young Woman (1930) is a perfect example of the photographer’s ability to pose his subject, putting her enough at ease that she shines in all her black-and-white glory as any debutante at her coming out party should. The pale coloration of flowers and fern may be icing on the cake of his composition, but the finishing touches of a master.

This was, after all, the age of retouching, and Van der Zee was a talented manipulator. Some might even have called him a magician of sorts.

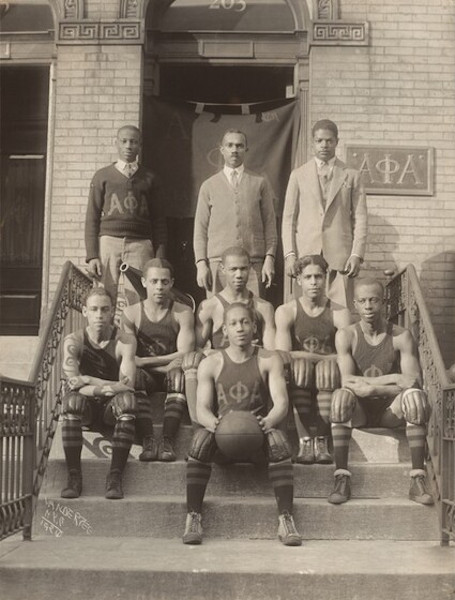

In Alpha Phi Alpha Basketball Team (1926), Van der Zee retouched under the eyes of the men and at the sides of their noses to smooth out shadows and wrinkles and erased shadows caused by heavy sunlight. This was likely achieved by drawing on the negative with an opaque graphite pencil. Those pencil lines blocked some of the light passing through the negative when it was used to make a print. And the less light that strikes an area when a photograph is printed, the lighter that area will appear. So, graphite lines in a negative create light or white lines in a photograph.

If the young women who posed in Blumstein’s Sales Girls (1930) wanted the rings their paychecks couldn’t deliver, Van der Zee complied by drawing the desired ring on a willing finger. A microscope image at 15x magnification revealed the ring that he created directly onto the negative.

No image was too difficult for this talented trickster. In one image, a 1920 photograph titled "Future Expectations (Wedding Day)," a young couple is presented in bride and groom finery, with a ghostly, transparent image of a child at their feet.

Perhaps the most iconic image in the exhibit is Couple, Harlem, (1932). There’s glamour here in the handsome couple, the woman wrapped in furs, standing alongside a shiny Cadillac; the man inside self-assured in his success. Journalist and musician Celeste Headlee, commenting on the image in her podcast hears Lenox Avenue, a main street in Harlem that her grandfather William Grant Still (known as the Dean of Black American composers) used as his inspiration for the eponymous suite he created.

The onlooker of this parade of Harlem’s finest, as well as its striving wannabees, can only wonder who was James Van Der Zee? How did the silver-lining images he created for his clients color his own life?

Born June 29, 1886, in Lenox, Massachusetts, the second of six siblings, he showed an early aptitude for the arts, playing piano and violin at an early age, followed in high school by a passion for photography. After a short stint of odd jobs in Harlem, he moved to Virginia as a newlywed, continuing photography work and teaching music. Yet Harlem still held sway over his ambitions, and by 1916, he had opened his own studio, shedding new light on his Black compatriots. A second marriage followed, along with his growing success.

For Van der Zee, his early Harlem success had time limits. When Prohibition ended, the demand for bootlegged liquor abruptly terminated for the white populace. Uptown commerce dwindled. For years he maintained an alternative business in image restoration and mail-order sales, but it wasn’t until the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1969 mounted an exhibition featuring Van der Zee’s Harlem on My Mind, that his work received the attention he craved.

When his second wife died in 1976, his life took a downward spiral until gallery director Donna Mussenden took on his cause, becoming his third wife and helping to bring new celebrities like Lou Rawls, Cicely Tyson, and Jean-Michel Basquiat into his life. (In later years, he would partially reclaim over 50,000 images from the Studio Museum of Harlem that he had signed away while destitute.) Before his death from a heart attack in 1983 at 96, he was given the Living Legacy Award from President Jimmy Carter and an honorary doctorate from Howard University.

The takeaway for this reviewer in studying Van der Zee’s subjects, even within the limitations of the images on display, is his ability to turn a photograph into a portrait. The portrait itself might be a lie, built on the expectations of his subject and his own creative manipulation. But the end result arrives at a work of art, and perhaps, a greater truth.

Author Bio:

Sandra Bertrand is Highbrow Magazine’s chief art critic.

For Highbrow Magazine

Images: Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art.

James Van Der Zee, Couple, Harlem, 1932, printed 1974, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund © 1969 Van Der Zee.

James Van Der Zee, Marcus Garvey (right) with George O. Marke (left) and Prince Kojo Tovalou-Houénou, 1924, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Avalon Fund © 1969 Van Der Zee.

James Van Der Zee, “Beautiful Bride,” c. 1930, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund © 1969 Van Der Zee.

James Van Der Zee, Alpha Phi Alpha Basketball Team, 1926, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (The Evans-Tibbs Collection, Gift of Thurlow Evans Tibbs, Jr.) © 1969 Van Der Zee.