Burkhard Bilger’s Discovery of a War Criminal in the Family in ‘Fatherland’

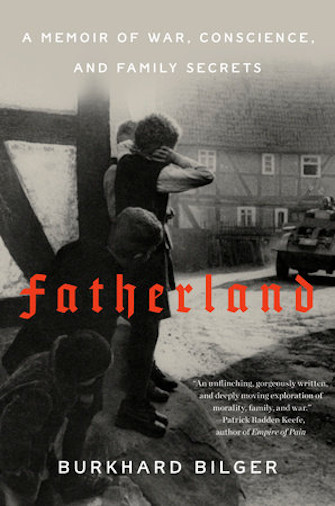

Fatherland: A Memoir of War, Consciences, and Family Secrets

By Burkhard Bilger

Random House

314 pages

“I was twenty-eight years old when my mother first told me that her father had been imprisoned as a war criminal.”

So Burkhard Bilger, a staff writer for The New Yorker, tells us in the early pages of his new memoir, Fatherland. Bilger’s maternal grandfather, Karl Gönner, served as a school principal, responsible for “re-educating” local children on behalf of the Third Reich. He was later named Nazi Party chief in the French province of Alsace, a region between France and Germany hotly disputed for centuries.

Some inhabitants of the border town of Bartenheim recalled Gönner as a man who intervened on behalf of villagers, saving them from Nazi persecution. But when the war ended, he stood accused of ordering the murder of a local man. (Gönner was eventually acquitted of this charge, though suspicions lingered.)

Many years after learning about his grandfather, Bilger decides the time has come to get at the truth buried in the past. He travels to the region, conducting both archival research and interviews with a few remaining survivors. This prompts ruminations on the nature of memory and the past:

“The further events recede from view, the more we flatten and simplify them in our minds, till history is just a series of cautionary tales: crime and punishment, heroes and villains.”

The opening chapters of Fatherland proceed at a leisurely pace. In a lengthy genealogical preamble, we learn in some detail about Bilger’s extended family and their upbringing before, during, and after the Nazis took power. There are long stretches about his grandfather’s personal history, most importantly his military service in the First World War. This seems notable mainly for cataloguing the severe injuries he sustained in combat; less compelling are authorial digressions such as a description of the all-Black 369th Infantry Regiment of the U.S. Army, known as the Harlem Hellfighters. Why this material is included is hard to say. We get more than a third of the way into Fatherland before delving into the Nazi years.

Soon after the liberation of France, Karl Gönner (called “Karl” throughout the book) was charged with ordering the execution of a villager aligned with the Resistance. A series of investigations followed, leading—many years later—to Karl’s official exoneration (though even that label was later rescinded by a German investigative committee, noting tersely “the above facts do not suffice to classify [Karl Gönner] as exonerated.”)

The horrors of the Second World War lived on for years. In the 1950s, German children enjoyed romping in long-vacated tunnels behind a church:

“Scampering through them after school, they found old rifles and bayonets, spades, human skulls, and unexploded shells … Old tanks became truck chassis, bayonets became screwdrivers, rifle barrels became garden stakes for tomato plants.”

At one point, Bilger happens upon a boisterous oom-pah band in the town of Aulfingen—“a few hundred half-drunk Germans” celebrating a crafts and music fair. This happy crowd, he writes, is “unconcerned by history,” caring little, it seems, that “Hitler and Goebbels reveled in the same country garb.”

Near the end of this somber, thoughtful memoir, the author makes an uneasy peace with his grandfather’s legacy. We find ourselves in difficult times, he concludes, all too eager to pass judgment on others and “fix” the past. “But the guilt that drives us can reach beyond penance or restitution to a conviction that something in us, or in our culture, is broken beyond repair. That our history is irredeemable.”

To his credit, Burkhard Bilger immediately adds, “I have never believed that.”

Author Bio:

Lee Polevoi, Highbrow Magazine’s chief book critic, is the author of a new novel, The Confessions of Gabriel Ash.

For Highbrow Magazine

Photo credits:

--Bundesarchiv, Bild 119-0289 / Unknown author (Wikimedia, Creative Commons)

-- Unknown author (Wikimedia, Creative Commons)

--Random House