The Unsettling Banality of Evil in ‘The Zone of Interest’

I never thought of myself as Jewish—if anything, I was culturally Jewish. I never practiced Judaism growing up, besides going to Hanukkah and Passover every year to pay respect to my grandparents and my heritage. Yet, the world sees me as Jewish. Maybe it is my last name, my curly hair, my big nose, or my Woody Allen-like mannerism, but my heritage is easy to guess.

Thus, to the world, I’m Jewish. Which means that, as a film critic, I now have a responsibility to seek out movies about the Holocaust and Jewish suffering. Inevitably, family members, friends, or colleagues will ask my thoughts on the film, and if there’s a new movie about the Holocaust, we all know what movie I will be fielding questions about. Sometimes people share anecdotes of how much it moved them, and ask what I thought. Best case, I nod politely and say, “Yeah it’s a harrowing story.” Worst-case scenario, maybe they ask me about how I viewed this film given everything going on in Israel and Palestine (a question far too complicated to explore, especially, as I’m just trying to enjoy my brunch). In reality, I often find myself wanting to respond: “Here we go again, another Holocaust movie.”

That sounds terrible to admit out loud and admittedly is probably politically incorrect of me to say, but it’s the truth. This is not to say that I believe artists are creatively bankrupt when they choose to tell a story centered around the Holocaust. Far from it. Wonderful filmmakers have broached the subject to great achievements. But for every Schindler’s List, there exists The Reader -- movies that are so shallow in their approach and worldview that they use the backdrop of genocide to elicit tears from viewers, often in the hopes of a successful Academy Award’s FYC campaign. I love Kate Winslet but did she really need to win her Oscar for a movie in which she plays a sympathetic Nazi who falls in love with a teenage Jewish boy? So, when I started hearing critics rave about the Oscar-nominated film, The Zone of Interest, which is centered around a Nazi family trying to build a perfect suburban life, all while living next door to Auschwitz, I must admit I was dreading the experience.

Ninety-nine out of 100 times, The Zone of Interest is a disaster waiting to happen and derail any director’s career. The premise alone is enough to turn off a majority of the audience and leave the remaining viewers apprehensive. I mean, a family drama about Nazis? That’s a tough sell.

Watching the movie, it became clear right away that any apprehension I had was replaced with sheer horror. Not a horror, brought about by discomfort in narrative focus, but rather the director’s truthfulness. Most period pieces try to replicate an aesthetic, but Glazer wisely chooses to replicate an atmosphere. In this world, the sound of a train signifies the loss of hope and the air one breathes consists of the ashes of the dead. Glazer forces the audience to experience Hell on Earth, and in doing so reveals a horrifying reality: If one lives in Hell long enough, one becomes indifferent to Hell.

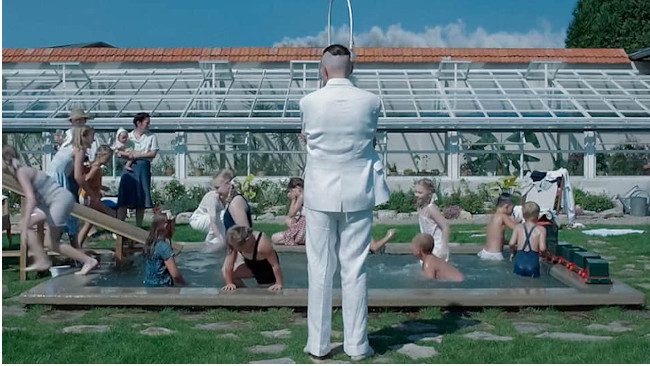

The film follows Rudolf and Hedwig Höss, a married couple with five children who live their idyllic middle- class suburban fantasy full of laughter and love in a beautiful home, with a picture-perfect backyard. A good father, Rudolf takes the kids on outdoor activities like swimming and fishing, while Hedwig stays at home and tends to the garden and prepares the meals. All the while, in this wonderful dream home that borders the wall of Auschwitz concentration camp, the sounds of gunshots, screams, trains, and furnaces serve as white noise for Rudolph, the Nazi commander, and his family.

Technically speaking, little happens within Glazer’s story, besides Rudolph working on a new crematorium, which he believes will increase productivity, all while trying to get a promotion to better support his family. Yet, the film rarely speaks about the intent of the crematorium. In fact, any variation of the word “Jewish” is missing from the character’s vocabulary. Rather, the language of genocide becomes statistical, so as to best increase efficiency, and in doing so, strip the prisoners of identity.

Everyone knows the feeling of hatred and being hated. It is a human emotion; thus, when Jonathan Glazer strips hate from the Nazi’s motivation, something feels disconcerting. Bigotry is easy to grasp. Racism comes from a place of stupidity. In The Zone of Interest, I never was under the impression that these Nazis hated Jews. I’m sure they did, but propaganda, offensive stereotypes, and bitterness never seemed to drive these characters. Rather, their appearance was that of indifference— indifference to suffering, indifference to humanity, indifference to the lives of Jewish people. In the eyes of the Höss family, they simply did not exist.

Watching the movie, I was waiting for an angry outburst from Rudolf and Hedwig where they parrot Hitler’s rhetoric, lies, and propaganda. It would have come as such a relief because I could compartmentalize their hatred and understand it as stupidity. Yet that outburst never comes to fruition, leaving me distraught. I had no answers as to how and why this family could lack passion in the killing of my people. Simply put, how could someone be a part of genocide of this magnitude without being overtly, comically, over-the-top racist? Hitler was a screaming maniac. Joseph Mengele, a mad scientist. Heinrich Himmler was a calculated, cold, military leader. In The Zone of Interest, Rudolf and Hedwig seem normal. They could be my neighbors, and I would never think twice about them.

What differentiates The Zone of Interest from other lesser films centered around the Holocaust is its refusal to engage in the tropes. The atrocities of the Nazis are so inhumane that filmmakers humanize these characters. Whether it is Winslet in The Reader falling in love with a boy, all while “accidentally” committing genocide due to her inability to read, or Tom Cruise in Valkyrie playing a real- life German soldier who conspired to kill Hitler. Even films that I love, such as Taika Waititi’s Jojo Rabbit, portray Sam Rockwell’s character, a Nazi officer disheartened by Hitler’s war. These portrayals of Nazis signify a belief in the artist that some form of humanity must have existed within some of those committing war crimes. After all, 8.5 million people were deemed members of the Nazi Party in 1945. They couldn’t all be perpetrators of genocide, could they?

The brilliance of Glazer’s direction and screenplay is its refusal to answer this question. We want to believe that the cruelty humans inflict on each other is explainable. Instead, The Zone of Interest forces audiences to sit with the psychological torment that evil is often inexplicable. Jewish people know this reality to be true. In some way or another, every Jewish person has some connection to the Holocaust. It’s unavoidable. Even if we didn’t lose relatives, our Jewish identity makes us synonymous with the 6 million Jews killed between 1941-1945.

I myself have heard countless times the concept of “the banality of evil” in my studies of the Holocaust. However, to understand is not the same as to accept. Maybe it was my naivete. Maybe deep down, I wished the truth to not be as simple as indifference towards my existence and the existence of my ancestors was the reason for the death of 6 million-plus people. To see it played out on screen was horrifying. I wept the entire runtime. I wept for the lives lost in the Holocaust. I wept in horror of the inhumanity on display. I wept in mourning to my Jewish identity that I may never fully understand.

Author Bio:

Ben Friedman is a freelance film journalist and a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine. For more of his reviews, visit bentothemovies.com, his podcast Ben and Bran See a Movie, or follow him on Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube: The Beniverse.

For Highbrow Magazine