Kay WalkingStick: A Native-American Artist for the Ages

History has shown that being an artist and a woman is no easy task. And being a woman and an artist and of biracial Cherokee-Scottish heritage is a mountainous undertaking on the road to success. Lucky for us, at 88, Kay WalkingStick is still up to the challenge—she has proven she can move mountains and seas and everything in between with the stroke of a brush.

The current exhibition at the New York Historical Society, Kay WalkingStick/Hudson River School, puts contemporary paintings from WalkingStick’s six-decade career in a vital and lively conversation with the museum’s signature landscapes by Cole, Bierstadt, Durand, and John Frederick Kensett, among others.

Such a dialogue can be both harmonious and divergent. Wendy Nalani E. Ikemoto, the museum’s senior curator of American art and a Native Hawaiian, has said that she wanted to see their collection of Hudson River School paintings through WalkingStick’s own eyes.

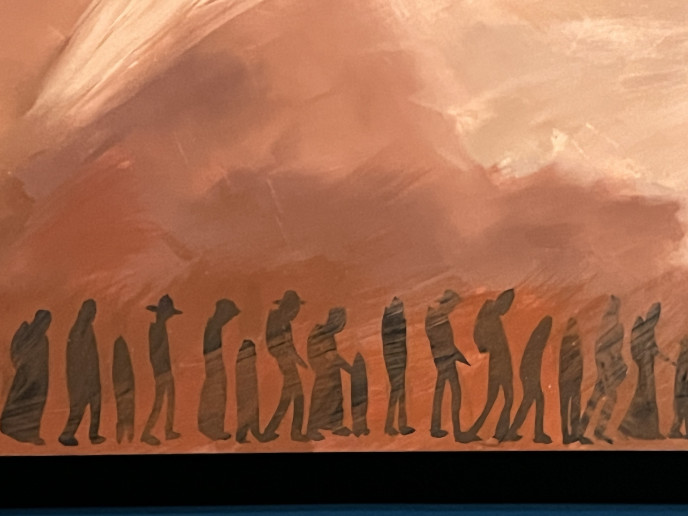

One of the most moving and majestic paintings of the artist’s is Farewell to the Smokies (Trail of Tears) 2007. It is a powerful diptych with a bare-bones depiction of monolithic peaks, contrasted with the departing hordes of the “five civilized tribes,” the human element in smaller scale across the bottom of the canvas. The predominating colors of the land are lush browns and greens, but the figures are almost invisible in their gray and ghostly shades.

The accompanying wall notes reveal that the artist, though born and raised in New York, felt the pull of her Cherokee ancestral land the first time she drove through the present-day Carolinas and Tennessee. In WalkingStick’s words, “It’s about the traumatic experience of leaving home—leaving this beautiful home.” The Trail of Tears is a reference to approximately 60,000 Native Americans that were forcibly exiled from their homeland after the Indian Removal Act in 1830.

A welcome inclusion in the exhibit is Four Portraits of North American Indians (1859) by Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902). Known for his expansively rendered landscapes, these oil sketches are sensitively done during a trip he made through what was then Nebraska and Oregon territory. The belief at the time was that these indigenous cultures would disappear from the earth as a result of the white man’s Manifest Destiny.

Jesse Talbot’s Indian on a Cliff (ca 1840s) is another rare portrait wherein the artist manages to idealize his subject—an iconic Native figure gazing across the vastness of his territory. Talbot was a member of the Foreign Missionary Society, which opposed the government’s Indian Removal policies.

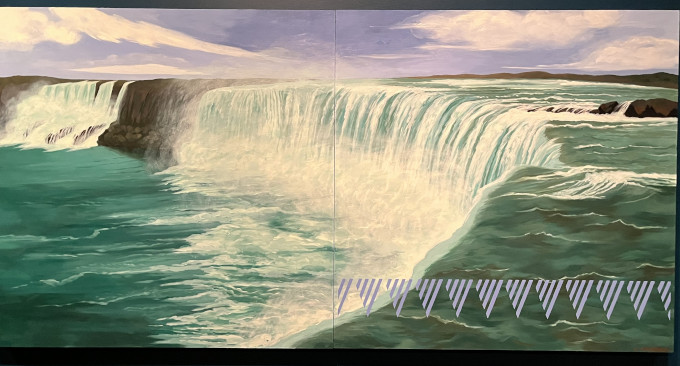

A crowd-pleaser central to the exhibit is WalkingStick’s Niagara (2022). Here, the artist puts the viewer at the brink of the falls, the water spilling across the twin panels, as much a majestic interpretation in its modernism as the earlier famed Realistic School. The Haudenosaunee pattern she imposes celebrates the original inhabitants. It would be hard to find a landscape more celebrated by white artists as “America,” but Walkingstick reclaims it with her indigenous markings.

What is the deeper reasoning behind these patterns upon landscape paintings that could well stand on their own? The explanation is simple. The artist is merely reasserting an indigenous presence, long erased in European settlers’ depictions of North America as a pristine and unpopulated wilderness. An informative and striking addition to the exhibit is a stoneware jar by Mohawk potter Steve Smith. Its Haudenosaunee pattern inspired the design WalkingStick used in Niagara.

A Louisa Davis Minot painting from 1818 is dotted by miniscule indigenous figures as identity markers hovering about the borders of the falls in her interpretation, but WalkingStick has replaced such stereotypes in her panels with the Haudenosaunee pattern.

In Saint Mary’s Mountain (2011), a geometric pattern prevails, inspired by Northen Cheyenne beadwork over the base of the mountain in present-day Montana. The pattern cleverly echoes the white-bordered lavender band running across the upswept mountain ridges, becoming an integral part of the composition.

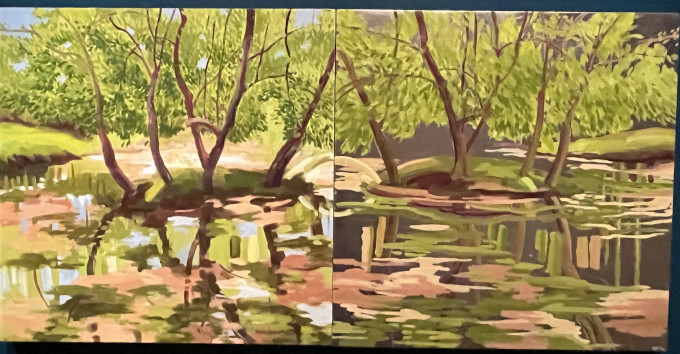

In July Low Water (2010), WalkingStick gives equal weight to each portion of the picture plane, resulting in a certain flatness that rejects depth in favor of a happy, geometric pattern of color.

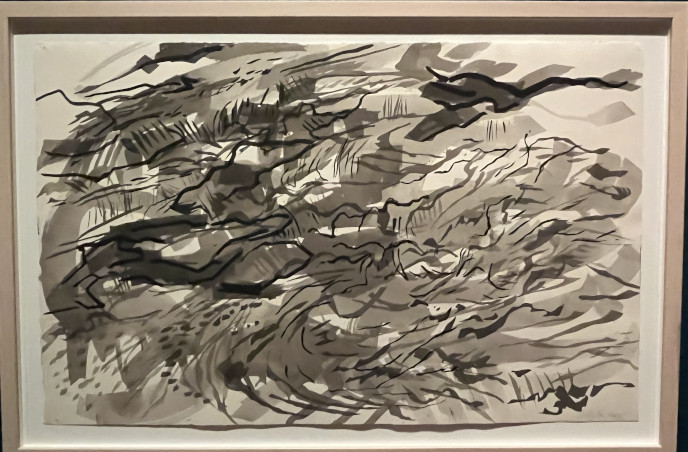

These mature landscape depictions hardly belie a mastery of other artistic forms. With Vermont Studio Center Creek III (1995), a striking abstraction on display, the artist sat in the middle of the river and mixed its water with sumi ink, replicating the rhythmic flow of her subject. Nearby, Asher B. Durand’s Catskill Study, NY (ca 1870) is a plein air work capturing the Northeastern region but with the objective of representing faithfully the subject, not “merely resembling it” in his words.

With such a rich panoply of artworks on display, it’s easy to be distracted from the long and impressive artistic trail of WalkingStick that precedes this single exhibition. Admittedly, this “dialogue” between the centuries is an illuminating effort, but it is WalkingStick’s own commitment to the natural world and affinity to her racial heritage in her art that stands out.

Discouraged from showing with other Native artists by an early dealer, WalkingStick disregarded the advice, continuing to paint. In 1973, at age 38, she started commuting to graduate school at Pratt in New York, where she shifted to painting abstractly and began to reconcile her biracial identity. She has shown consistently in group and gallery exhibitions, while neglected by powerhouse institutions -- until recently.

The major breakthrough changed in her eighth decade, with the opening of her career retrospective in 2015 at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. “I had to come to terms with this idea that I am as much my father’s daughter as my mother’s,” she has said.

Many of the country’s major art and cultural institutions have been rethinking their collections in an ongoing effort of reclamation of our diversified roots. This exhibition stands rather as a conversation between earlier depictions of the country’s arcadian wonderland from a white perspective and a contemporary Native American’s masterly and mature works. It’s an overdue exemplary tribute, and one that surpasses a merely “woke” nod to another indigenous artist.

According to WalkingStick, “I hope viewers will leave the museum with a renewed sense of how beautiful and precious our planet is . . . [and] with the realization that those of us living in the Western Hemisphere are all living on Indian Territory.”

This exhibit is on view at the New York Historical Society through April 14, 2024.

Author Bio:

Sandra Bertrand is Highbrow Magazine’s chief art critic.

For Highbrow Magazine

Image Credits: Sandra Bertrand