Edward Hopper’s New York: A Study in Isolation at the Whitney

“Sometimes talking with Eddie is just like dropping a stone in a well, except that it doesn’t thump when it hits bottom.”

That quote, by Edward Hopper’s artist wife Jo, sums up not only the mystery of the man with whom she was to share her life, but the mystery of the artwork itself. Perhaps no other realist American artist of the 20th century has continued to perplex, mystify and haunt museum-goers as much as Hopper. And visitors to the Whitney Museum’s current retrospective, Edward Hopper’s New York, will not be disappointed.

Will this collection of 200 works on display, spanning over six decades of his life, solve the mystery of its power over us? Hardly. But then, all great art poses more questions than answers about life’s mysteries.

Hopper was born in Nyack, New York, in 1882, but his heart quickened early to the city some 37 miles to the south. From 1908 to 1915, before settling into the modest apartment on New York City’s Washington Square North that would remain home base for the rest of his life, he lived first on West 14th Street and East 59th. True to his nature as an American flaneur, he roamed the streets and rode the elevated trains when not studying at the New York School of Art and Design (later becoming the Parsons School of Design). Many of these strolls became the groundwork for Hopper, a solitary witness discovering men and women living out their lives behind city apartment windows; late-night café habitués and loners—an anonymous urban populace of strangers that would people so many of his canvases.

The Whitney is ground zero for promoting and preserving the legacy of this iconic genius. Its holdings comprise 3,100 works and represent 10 percent of the entire collection. The first painting purchased was Early Sunday Morning (1930). It is a study in isolated storefronts, a horizontal view where a barber pole and a fire hydrant seem to be stand-ins for an absent populace. It’s as good a place as any to begin our journey to understand his obsession with the city. Alfred Barr, the Museum of Modern Art’s founder, was stunned by Hopper’s indifference to skyscrapers. After all, the Chrysler Building, towering over Manhattan’s skies, was built the same year of the Whitney’s purchase.

But such monolithic structures were not to be fodder for Hopper’s brush. The artist instead was drawn to the unsung structures and hidden corners, the paradoxes of the new confronting the old. The people he depicted were placed as if on a stage set, gazing inward or outward, inscrutable and reticent to share their often solitary and muted lives with the onlooker.

In one of the few instances that Hopper expressed the importance of figuration in his works for publication, he also let loose on his rejection of abstraction:

"Great art is the outward expression of an inner life in the artist, and this inner life will result in his personal vision of the world. No amount of skillful invention can replace the essential element of imagination. One of the weaknesses of much abstract painting is the attempt to substitute the inventions of the human intellect for a private imaginative conception. The inner life of a human being is a vast and varied realm and does not concern itself alone with stimulating arrangements of color, form and design."

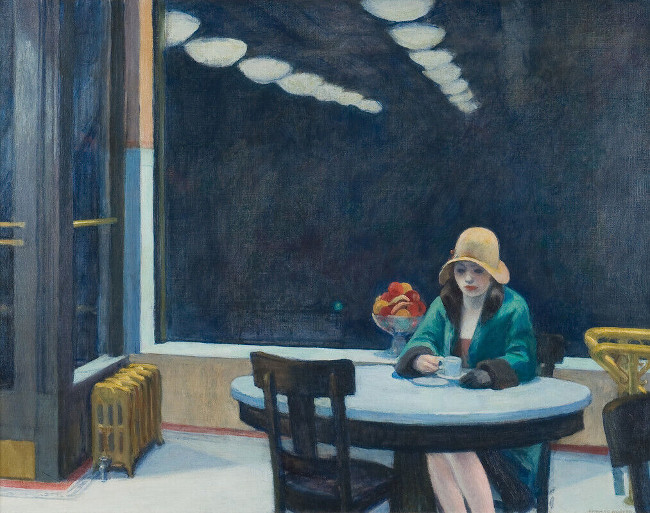

Some crowd draws would have to include the Automat (1928). A young woman sits with a coffee cup after dark. A glare of fluorescent lights complete the scene. Room in New York (1932) reveals a couple playing out a moment of separation in their apartment. He is hunched over his newspaper while she toys at an upright piano, a table defining the space between them. Office at Night (1940) depicts a typical office scene. The preoccupied boss and his secretary—a familiar scene. She observes him at work but does not intrude.

One of this reviewer’s favorites is New York Movie (1939). The usherette depicted in the painting was none other than Hopper’s artist wife Jo, Josephine Verstille Nivison, a former art-school classmate who shared his intrinsic devotion to New York. Like Hopper, in 1923 she was spending the summer painting outdoors. The two married the following year—he, 42; she, 41—and they lived and worked together at 3 Washington Square North for the rest of their lives, alternating with a home they built on Cape Cod.

No fewer than 53 sketches comprised his preparatory work for New York Movie. Film and theater were major players in the lives of this couple and the Whitney has given such ephemera ample space. One room has been given over to archival footage of plays projected on a wall that they attended. An accompanying vitrine holds rows of theater ticket stubs they religiously kept. The takeaway of this obsession is in Hopper’s own oeuvre, where his human landscape can act as a springboard for a story he leaves the onlooker to complete.

A recent generous bequest to the Whitney from the Sanborn Hopper Archive has brought to light correspondence, photographs, and journals that together inspire new insights into Hopper’s life in the city.

Early signs of the artist’s solitary leanings can be found in his first etchings. Night Shadows (1921) depicts a dark aerial view of a lone figure, the city building rising behind him, dwarfing his role in the composition. And what are we to make of his self-portrait from 1903-06? A serious young man peers over his shoulder at the viewer, emerging from a dark interior, giving little or no clue to his thoughts. A later self-portrait from 1925-30 shows a similar confrontation, but here a hat completes the picture, throwing his gaze into shadow.

Whatever legacy Hopper has left in his pictorial journey, it would be amiss not to mention his mastery of light and shadow. One of the best examples of this is Morning Sun (1952). A single woman basks in the light that pours into her bedroom, as integral a part of the scene as the subject herself.

This major retrospective is organized by Kim Conaty, Steven and Ann Ames Curator of Drawings and Prints, with Melinda Lang, Senior Curatorial Assistant. Obviously curated with great attention and love, the result is both tantalizing and instructive, leaving it to the viewer to form his or her own answers or questions about who the man and artist called Edward Hopper really was.

Edward Hopper’s New York at the Whitney Museum of American Art is on view through March 5, 2023.

Author Bio:

Sandra Bertrand is Highbrow Magazine’s chief art critic.

For Highbrow Magazine

All images courtesy of the Whitney Museum:

- Room in New York (1932)

- Automat (1927)

- Sunlight in a Cafeteria (1958)

- New York Movie (1939)

- Early Sunday Morning (1930)

- Office in a Small City (1953)