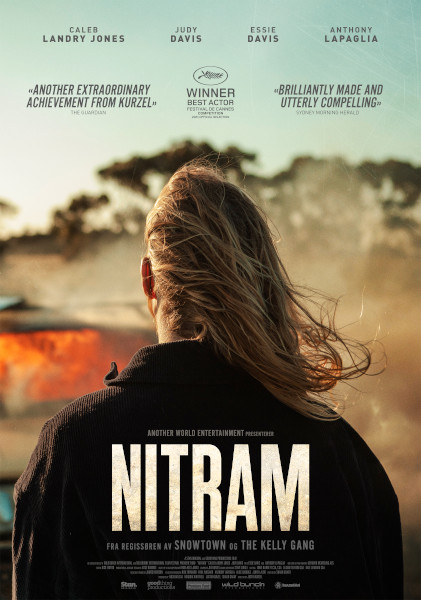

‘Nitram’ Is a Devastating Portrait of Isolation and Violence

In 2011, writer Shaun Grant and director Justin Kurzel made Snowtown, a nightmarish tale of ennui and brutality to rival Michael Haneke in its bleak conception of human nature. A decade later, Grant and Kurzel return to familiar territory with Nitram, which also draws on actual events to unearth something horrific in the quotidian. Nitram details the events leading up to the 1996 mass shooting that took the lives of 35 people in Port Arthur, Tasmania; though it opts not to use the perpetrator’s real name, instead using an old schoolyard epithet.

Nitram (Caleb Landy Jones) was badly burned as a child while playing with firecrackers. Now in his late 20s, we see Nitram setting off fireworks, and annoying the neighbors, in the back garden of the suburban home where he lives with his unnamed parents (Anthony LaPaglia and Judy Davis). Nitram’s dad has his hopes pinned on setting up a bed-and-breakfast, which he will run with his son. Nitram’s mum grows suspicious when her son declares that he is moving out to live with his new friend, Helen (Essie Davis), an heiress and former singer in her 50s who owns a large, ramshackle house overrun with cats and dogs. Nitram becomes the latest stray Helen takes in, but this alliance of outsiders is cut dramatically short.

What is so chilling about Nitram is the flatness of its pitch. Kurzel offers no dramatic signposts; we traverse a steady continuum of events, mimicking the alienation of its characters, who recognize but never express their presentiment. Nitram draws its power from this inevitability; the everyday events we see are leant a grim significance; we are riding with the characters on a set of tracks towards devastation. Like Jed Kurzel’s score of sustained notes interrupted by bursts of discord, when the final violence does erupt, it is all the more disturbing for emerging out of the shallow depth of field that cinematographer Germain McMicking maintains.

There is an effulgence to the photography that makes what is captured all the more unsettling, harnessing the lambent light of the location to disquieting effect. Kurzel uses the landscape in the same way that directors like Nicolas Roeg, Peter Weir, and Ted Kotcheff did; its breadth and brightness speak to a well of cruelty that bubbles beneath the manicured lawns. Nitram’s realism is twisted through a skewed viewpoint; everything appears off-kilter; life is viewed at disconcerting angles that speak to a medicated perspective, placing us in an uneasy position of complicity as we share the layer of distance separating Nitram from the world.

This stylistic estrangement mirrors the detachment with which the crime is carried out. It is an act that resists proximity -- its implications are too overwhelming to process, and to lavish it with technique would reduce it to spectacle. Instead, the violence assumes a methodical quality, taking its cues from Alan Clarke’s Elephant (1989) in its attempt to uncover the monstrosity of the act by anchoring it to banality. The eerie naturalism of Gus Van Sant’s ‘death trilogy’ is another touchstone; speaking to the steady accumulation of Nitram’s death drive as he toys with the possibility of his destruction, seeing the terminus at every point of contact, locked into deleterious patterns that assume the weight of identity as they become entrenched.

Nitram is distinguished by three outstanding but contrasting central performances. Jones has become a screen presence who evinces vulnerability and unease in equal measure, and he is sensational here. Jones conveys an inner world of rage and confusion with tremendous subtlety, lending a tragic gloss to Nitram’s childlike simplicity and blundering attempts at social engagement. It is a frank and fearless portrayal of mental illness left to its own devices. Jones is attuned to a different frequency here, his countenance drifting towards opacity; the less of Nitram’s inner life Jones allows us to see, the more terrifying his presence becomes.

Davis and LaPaglia share the audience’s foreboding, but embody different forms of despair. Davis wields a discreet power as the family’s psychological tyrant, but the role requires her to chart her waning influence within the limitations of her character’s forbidding demeanor, a task to which she is equal. LaPaglia brilliantly evokes the strain and incomprehension of seeing who his son is becoming. But rather than present an implacable front, he slips inwards, teetering on his narrow ledge of optimism with a stunning display of apprehension and emotional collapse. Both Davis and LaPaglia struggle with the implications of what they have created.

A confluence of rejections, thwarted hopes, and missed opportunities feed into the quiet desperation Davis and LaPaglia communicate with such force. They channel their failures into defensive postures, but Nitram projects his rage onto the world. Nitram complains that “I’m the one no one listens to,” and he demands to finally be seen, heard, respected, and feared. In seeing a character struggle with so much that he cannot adequately express, seethe with troubling impulses that go unchecked, and fail to find a way to channel his energies healthily, one can’t help but see parallels to the lost souls sucked into the darkest recesses of the Web.

What Nitram makes clear is that this rage has always been there, and will find whatever vessel it can. Nitram recognizes echoes of his own dislocation in the media; he reifies his final act by recording it on his camcorder, lending it social weight, ratifying it in the eyes of the world.

As we watch Nitram’s options gradually narrow, as the frame tightens, we understand that there were points of exit, but they got lost in the ominous glow that bathes everything in the unforgiving light of loneliness and revenge, leaving us to bear helpless witness.

Author Bio:

D.M. Palmer is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.

For Highbrow Magazine