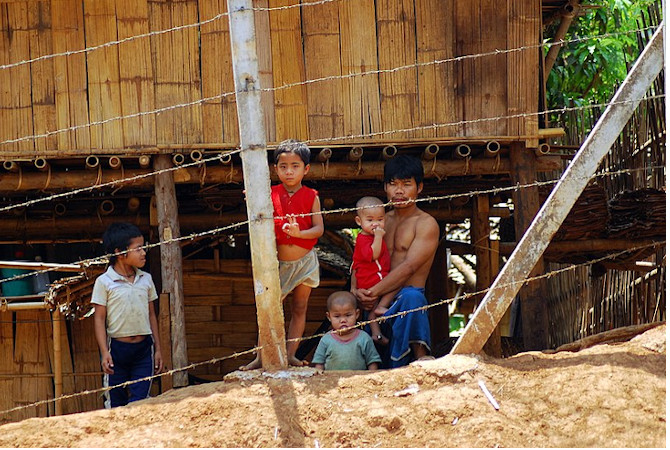

Myanmar’s Ethnic Minorities Are Forced to Fight, Resist, or Flee

Last October marked a significant shift in the longstanding conflict in Myanmar, the world's oldest ongoing war. Several ethnic resistance armies joined forces, initiating a campaign of coordinated attacks that are succeeding in pushing the Tatmadaw (Myanmar government army) out of the ethnic states. Previously, it appeared that each anti-government militia and armed group fought independently. However, there's been a notable change as an increasing number of them rally behind the National Unity Government. Ethnic leaders are unified in their goal to overthrow the military junta, which seized power in a 2021 coup, and establish a federal democracy modeled after the United States.

Such is the depth of hatred towards the regime that entire units of the Tatmadaw, the Myanmar Army, have either surrendered, deserted, or defected to the rebel side. With the tide shifting against them, the military leaders in Myanmar are growing increasingly desperate. To bolster their dwindling ranks, they've resorted to forced military conscription. According to the junta's estimates, among the nation's 56 million citizens, approximately 6.3 million men and 7.7 million women are deemed eligible for conscription, and the Tatmadaw is adamant about drafting them all.

The strict enforcement of the law, with its harsh measures, like scooping young people up off the street and forcing them into the army, not only worsens the refugee crisis in Thailand but also backfires on the junta. Instead of obeying, young individuals are choosing to risk their lives by leaving the country or joining the resistance.

Twenty-one-year-old Sai Su Thamma from Lashio, Northern Shan State, sought refuge in a camp in Northern Thailand upon learning about the conscription. “I heard the Burm[ese] army’s new law that everyone from the age of 18 to 45 must serve in the army for three years. If anyone disobeys the law, the punishment [will be to] go to jail for five years,” he said.

While recruitment and coercive measures are already underway, the full enforcement of the law, including punishment and pressure on families of those who refuse to serve, is scheduled to commence at the end of March.

Sai Su Thamma expresses that the Tatmadaw's policy is unjust: “This policy is not right. And I don’t want to join any army. As they just want to maintain their power. Moreover, I don’t want to fight and kill people in the same country, or my own people."

This sentiment underscores a significant issue for ethnic minorities who already endure government oppression and war on the frontlines. If drafted by the Myanmar military, they would be compelled to kill their own people.

Two siblings, Sai Pandawa, aged 22, and his sister, Nang Sing, aged 19, hailing from Laikha township in Southern Shan State, recounted their ordeal. Their father received a letter demanding their enlistment into the army two years ago. Despite his efforts to plead for their exemption, the general remained unmoved. The general warned that any attempt to escape or aid the children in their escape would result in the seizure of the family’s property.

Sai Pandawa spoke of his father’s courageous act of love. “My father came back home and decided to let them take whatever they want, and we moved.” The family surrendered their village property and resettled in the city, where Sai Pandawa became a monk and pursued studies in the temple, while his sister Nang Sing enrolled in medical school. It's common for Shan boys to receive education in monasteries, typically exempting them from military service. The family believed they had found a solution, but the new conscription law caught up with them, disregarding their monkhood and student status, and the army demanded both of the children.

Sai Pandawa said, "My younger sister [and I]…we don’t want to be in any army, as we know we have to fight and kill each other." Consequently, their father made the decision to send them to Thailand. Presently, Nang Sing, formerly a medical student, works as a house cleaner, while Sai Pandawa, compelled to abandon his monkhood to support himself, is employed as a construction worker.

Thaw Reh Est, a 47-year-old male and Secretary Number Two in the Karenni National Progressive Party (KNPP), the government in exile of the Karenni ethnic group, clarified that due to the control of villages by the Karenni resistance armies, the Tatmadaw faces difficulties enforcing conscription. Nevertheless, Karenni youths who have migrated to cities for study or work remain at risk of being apprehended.

He elaborated on how the conscription law was unfolding: “Some flee to revolution areas” joining the resistance. “Some try to find their own way to Thailand. Some young people will be caught and conscripted to the army. And some will run away." He smiled a sad, ironic smile and remarked, "But the military is also smart enough, perhaps, not to equip them with weapons.”

Tragically, he concluded that some ethnic conscripts “mixing with the others will have no option.” The Tatmadaw, he emphasized, would not permit their escape. “They have no will to fight with their brothers, but they are forced to stay in the camp.”

Author Bio:

Antonio Graceffo, a Highbrow Magazine contributor, is a Ph.D. and also holds a China-MBA from Shanghai Jiaotong University. He works as an economics professor and China economics analyst, writing for various international media. Some of his books include: The Wrestler’s Dissertation, Warrior Odyssey, Beyond the Belt and Road: China’s Global Economic Expansion, and A Short Course on the Chinese Economy.

For Highbrow Magazine

Photo Credits: Depositphotos.com; Mikhail Esteves (Wikipedia Commons); Trocaire (Wikimedia Commons); Ecrusized (Wikipedia Commons)