Conspiracies and Trauma Take Flight in 'Cosmic Dawn'

Jefferson Moneo’s offbeat genre piece signals something bigger to come.

It is never a good sign when cults become an object of fascination. It may be that recruitment is much easier than it used to be, but people are reaching for solutions in the strangest of places right now, trying to explain instability by looking for the great clarifying figure who will make sense of everything. There is something approaching nostalgia for the certainties that cult membership affords, a fixed identity with a solid set of precepts. Cosmic Dawn marries two current media obsessions by situating its cult activity within the world of alien visitation.

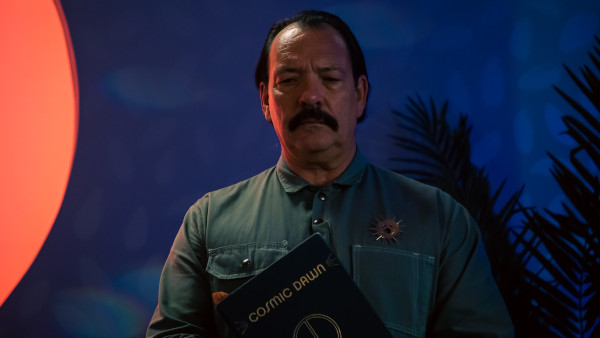

Aurora (Camille Rowe) is struggling to process the death of her mother when she was a child; she maintains that her mother didn’t die, but was abducted by an alien craft. At a low ebb, and looking for something to buttress her assertion, Aurora meets Natalie (Emmanuelle Chiriqui), who introduces her to the Cosmic Dawn, a UFO cult led by the ‘visionary’ Elyse (Antonia Zegers). Aurora is told by Elyse that she has been chosen as a vessel, and the Cosmic Dawn prepare for the blood moon that will see the cult’s prophecy fulfilled. Cosmic Dawn flits between timeframes, detailing Aurora’s initiation, and the ramifications of her departure.

Moneo’s second feature is a sly piece that manages to encompass a variety of tones, textures and topics within its ostensibly genre housing. Stylistically, it evokes the VHS hallucinations of Panos Cosmatos and Peter Strickland’s uncanny artifice, yet there is also a ‘90s indie sensibility at play which brings to mind the likes of the Zellner brothers and Joel Potrykus – a comparison bolstered by the presence of Potrykus regular Joshua Burge as Natalie’s sardonic husband, Tom. Cosmic Dawn is clearly not ashamed of its schlocky lineage – the ‘80s TV sci-fi aesthetic of the production design makes the cult’s compound all the more unsettling – but Moneo inserts elements that raise it above the standard exploitation fare.

Music is an integral part of Cosmic Dawn’s success; Andrew VanWyngarden’s score blends seamlessly with the songs from his band, MGMT, to create a sonic space that is both nostalgic and otherworldly, echoing the techno pulse and vaporwave vistas of Oneohtrix Point Never. It is music that triggers a keen sense of loss for something that may never have been experienced, a lost ideal that has been handed down.

Vlad Horodinca’s photography offers a contrast between the Day-Glo palpability of Josh Marr’s visual effects and the washed-out palette of the everyday world; the camerawork tightens in a barely perceptible way, signaling the contraction of its subjects’ choices, the frame admitting little room for manoeuvre.

The film’s fractured narrative structure increases a feeling of disorientation; past and present selves run parallel to underscore that these planes of existence are inextricable; this has all been preordained; the story has already been told, and Aurora is merely moving toward her fate.

Dialogue is delivered with a consciously unnatural cadence, which brings tension to every exchange, as if there is a subtext to every word which has to be deciphered. The result is to chip away at the certainties of the self, which is exactly what cults endeavour to do. Cosmic Dawn stands alongside films like Sound of My Voice (2011) and Brigsby Bear (2017) in capturing the irrational codes and critical lapses that a hermetic lifestyle can engender.

Rowe delivers a performance that conveys the perplexity of the world Aurora inhabits within and without the Cosmic Dawn; her actions have a medicated sheen, betraying an unwillingness to confront life on its own terms. We see the world of Cosmic Dawn through Aurora’s bewildered gaze. Burge begins as another rudderless soul evincing an amiable lassitude, but he subtly adjusts his characterisation of Tom in line with Aurora’s shifting perception of him; it is a perfectly weighted performance, which manages to be substantial without being showy. Zegers is mesmeric as a bird of prey who is at peace with her capacity to claw at the fabric of reality. Elyse is majestic yet minatory; her threat is manifest yet never articulated; and Zegers skillfully invokes a shuddering unease in her soothing locutions and beatific demeanour.

The most pertinent point of comparison for Cosmic Dawn would be Jeremy Saulnier’s Blue Ruin (2013); it is a sophomore genre film that manages to be bigger than its genre trappings. It traces a kind of retro-futurism, a past vision of an unfulfilled future, with enough self-awareness to stave off campiness. Moneo’s screenplay draws on previous cults for some of its lore – most notably Heaven’s Gate – but its tarnished utopia feels distressingly close to anyone who has delved into the darkest recesses of the internet, and come back to tell the tale.

Watching Aurora get lost in the halls of arcane, seeking the definitive truth that will release her from her pain, it’s not hard to see countless others who have fallen down similar rabbit holes. Moneo flags up the line between the ridiculous and the deadly, which so many of these movements tread; how absurdity overlaps with the gravest designs; emotion and nostalgia are leveraged against the adherents, until they understand who they are serving. Seeing the real-world impact of the cult’s activities, it is not hard to draw contemporary comparisons. Trauma animates many such movements, and whether one chooses to approach Cosmic Dawn literally or figuratively, it deftly examines the lengths to which grief and loss can drive a person.

Author Bio:

D. M. Palmer is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.

For Highbrow Magazine