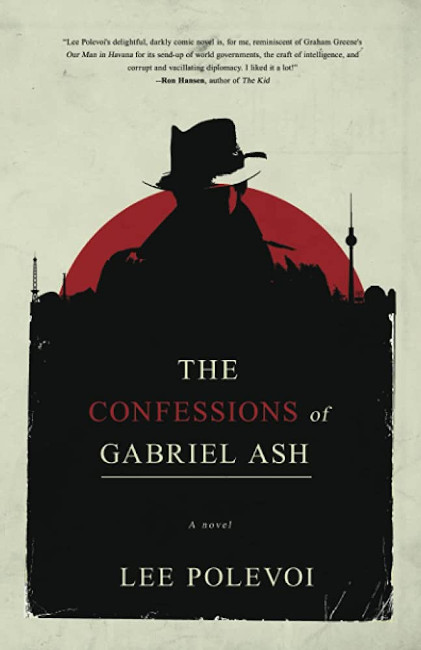

New Novel Weaves a Tale of International Intrigue

1982. Gabriel Ash serves as United Nations chief delegate for the fictional East European nation of Keshnev. As war rages in the Falklands, a series of scandalous incidents in New York—some self-inflicted, some not—prompts the Minister for State Security to recall Gabriel back to his adopted homeland, deep behind the Iron Curtain.

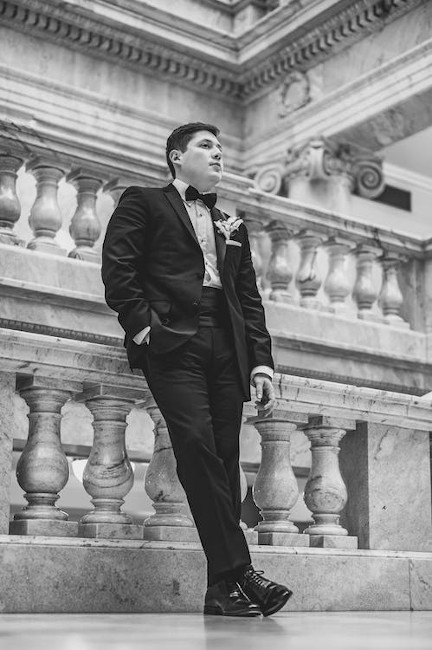

Two days after my arrival in Keshnev, the bellhop delivered a printed invitation to a state dinner at the Foreign Ministry. A tailor conducted a personal fitting and, three hours later, a sleek, custom-made tuxedo appeared—this, in a country where it takes weeks to buy a loaf of bread. “That’s more like it,” I said, tipping the elated bellhop an extra 30 klei.

My euphoria lasted only until the limousine ride through the city. The notorious Planz Quarter was once the haunt of art smugglers and fallen European playboys; now I saw row after row of crumbling block towers. Old men gazed out of broken windows. Feral dogs clashed over the spoils of an overturned trash can. From my backseat window, I saw two men roughing up a third man in an alley. The assailants raised their tombstone faces as the limo passed, then resumed pummeling their victim.

Oh, Keshnev!

Nausea rose in my gut, stomach-wrenching revulsion at what had become of the old country. I hated Petrescu for ordering my return, hated the secret police eavesdropping on my hotel room, hated even the man under siege in the alley. The sooner I could plead my case and expedite passage home, the better.

Government buildings loomed up on every corner, each structure with its own hideous pillars and statuary. Klieg lights installed on the roof of the Foreign Ministry building—itself, a bleak ten-story monolith—beamed down on arriving guests. I fell in with a crowd of cigar-puffing apparatchiks and their brawny wives, all of us moving down a herringbone-parquet hallway into a stately ballroom. The mincing waiter led me to a table in the rear, far from the podium and head table, around which the evening’s festivities would revolve.

I sat alone, simmering. Too many ups and downs for my dignity. First my unheralded crossing the border into Keshnev, then the surprise VIP treatment at the Metropole, and now at an elegant state dinner, this ridiculous seating arrangement. Would I ever receive a proper welcome home, or had I become persona non grata? It seemed the powers that be couldn’t make up their minds.

Eventually, two couples and a single woman—small-boned, with dusty blonde hair, in her mid-thirties—joined me at the table. Of the husbands and wives, I registered little beyond ample waistlines and boisterous high spirits. Vera, as the blonde woman introduced herself, held far more interest for me. She had an appealing smile, but something in her voice, the slight tilt of her head, and the way the chandelier light caught her face suggested some underlying sorrow. A self-described lowly morgue technician, Vera was only attending tonight’s dinner because her sick boss couldn’t make it. In a green, low-cut dress, she charmed us all with tales of berserk mourners and cadavers gone missing.

“Is true what they say?” One husband, a beefy gent with eyebrows like furry caterpillars, pumped his fist up and down in a universally obscene gesture. “Men come to morgue, make yaki-yaki with dead bodies?”

The wives roared with laughter; they’d come tonight to be entertained, and by God, this was entertaining. I watched Vera fiddle with a gold band on her finger.

Dinner was being served at other tables, notably those nearest the podium. As for the rest of us, the plates of scrawny chicken breasts drowning in turnip sauce would arrive on the waiter’s timetable, not ours. In Manhattan, I would have loudly complained about this appalling lack of customer service. The others around the table seemed grateful just to be here.

And there was wine.

Upon discovering a diplomat in their midst, talk among the couples turned to conflict in the Falklands. The husband with squiggly eyebrows had strong feelings about the war, as did his drinking buddy, a middle-aged man so tightly cossetted into a rented tuxedo that his eyes bulged like a frog’s. Why? these men and their wives wanted to know. Why did England go to war in the first place? Why not welcome the junta’s willingness to take the colony off their hands?

“Two bald men,” I replied.

They gawped at me, witless as cows.

“Someone far wiser than I am said, the war is like two bald men fighting over a comb.”

Vera's laugh cued the others and briefly, hilarity reigned. Swept up in anti-Western fever, Eyebrows pounded his big Communist fist on the table. “Screw England! Screw Margret Thatcher!” His pal Frog Eyes agreed. “Screw Iron Lady!”

The wives guffawed, nearly in tears. Vera sighed and turned her button-nose profile elsewhere.

“You tell Iron Lady, OK?” Frog Eyes said. “Tell her for us, Screw you.”

“Sure,” I said. “Anything else?”

“America, too!” he shouted. “Tell all of them, Screw you.”

I took a sip of the disastrously inferior wine, sensing Vera’s embarrassment on my behalf. “At the UN, I serve as the voice of the People,” I told the couples. “Therefore, I serve as your voice.”

Excited murmurs swept through the ballroom. Curtains opened, admitting a pair of white-haired commissars in shiny tuxedos slowly heading towards the podium. A third man followed, wearing a gray field uniform and black hobnail boots. All eyes fixed on him as he and the commissars settled at the main table. Even from this polar distance, I knew who I was looking at. Thicker and stockier than I remembered, and still sporting an implausible full head of black hair.

Minister Petrescu, in the flesh.

The ballroom grew deathly silent, as quiet as Vera’s morgue, until someone remembered to applaud. This triggered an ovation sounding much more supplicatory than heartfelt. Across the ballroom, a trio of musicians in lederhosen and Tyrolean hats struck up a lively polka. The two couples at the table, resigned to dinner not coming anytime soon, headed for the dance-floor.

“These people, I apologize for,” Vera said. “Probably they are drinking before they come here.” She noticed my sickened gaze at Petrescu. “The Minister … Do you know him?”

“From long ago.”

“Old friends! But why are you so much away at the table?”

I smiled, unable to choose from among my countless infelicities. I touched her hand, the one with the gold wedding band. “May I have this dance?”

The Tyrolean band played a lilting Alpine melody, as guests in their once-a-year evening wear waltzed across the dance floor. Holding a woman for the first time in weeks felt revelatory—the clean smell of Vera’s neck, her breasts in the cocktail dress pressed against me, the exquisite nestling of her hip and my loins, a sort of carnal joint-and-beam arrangement.

“Why didn’t your husband join you this evening?”

Vera raised her head from my shoulder. “What? Oh—no husband. The ring is a … convenience.”

“Deceitful, too.”

She laughed, did a quick twirl on the dance floor. “Sometimes I like to be with the living!”

A short man came to his feet at a table nearest the podium and began addressing the guests. His bowtie was askew, his tux wilted from sweat. In a booming voice, he introduced himself as mayor of Trevya, a factory town in the southern provinces. The mayor lifted his wine-glass and made a slurred toast to the people of Keshnev, combining praise for their national fortitude with a drunken, weepy account of misfortunes in his personal life. The commissars glared in silence, while Minister Petrescu’s attention seemed locked in on a bowl of borscht set in front of him. A merciful waiter finally took the sniveling mayor by the arm and guided him away.

The music resumed, a jaunty Polonaise that got guests dancing again, though now with spirits considerably subdued. Vera and I drew closer, a newfound intimacy borne out of this awful, shared experience.

“You do not talk much about what you do,” she said. “For a man, this is strange.”

“What would you like to know?”

“Why you are here in Olt, not at UN.”

“I’ve been recalled.”

“‘Re-called’? What is that?”

From the dance floor I had a clear view of the Minister, still looking down and contemplating his borscht. Probably he had no idea I was even here.

“Some bad things happened in New York,” I said. “You could say I’ve come back to atone for my sins.”

Vera’s face went white. “Atone to … him?”

“Don’t worry. It’ll be no more than a scolding.”

“No,” she whispered, clutching my hand as we danced. “Here can be so much worse.”

I smiled, feeling as stupidly sentimental about life as the mayor of Trevya. “Vera, are you concerned about me?”

She looked up—wounded blue eyes, an almost unwilling smile—as if the two of us shared the same thought. Tonight didn’t turn out so badly after all. I leaned in and kissed her.

“Ne valusca,” I said. “No more sadness.”

Moments later—after bidding farewell to the inebriated couples at our table—Vera and I stood outside on the steps of the Ministry building. The klieg lights on the roof had shut down, casting the ten-story structure into darkness. Only a few cars were visible on Strata Leniniskii, even fewer people. Vera drew her coat tight against the evening chill, her gaze on me eager and acquisitive—Your place or mine?—and we kissed again, more urgently than before.

Suddenly a hand clamped on my shoulder and spun me around. I faced a burly man in a trench coat and a black fedora. A second man, dressed like his partner minus the hat, took hold of Vera’s elbow and led her towards a waiting car. Vera struggled. The hatless man slapped her hard across the face.

“Hey!” I cried.

I took a step forward but arms thick as cordwood enveloped my chest from behind, a python grip steadily cutting off my oxygen supply. Before I was about to pass out, I saw the hatless man shove Vera into the car and, as it sped away, her bruised, mascara-streaked face pressed to the window. The hatless man signaled his partner to release me.

“What—” I gulped air. “What the hell is going on?”

“This is to inform you,” the man with the fedora said. “You are under arrest.”

Over my protests, the two men bundled me back inside the Ministry building, down a hallway and into a metal-grille elevator cage. No one spoke during our interminable ascent, and I kept my trembling hands by my sides, certain they could hear every thump of my jackhammer heart. Who were these men? What did they want? The elevator opened on the top floor to an empty corridor reeking of urine and garbage. The hatless man unlocked a door at the end of the corridor and pushed me up steps to yet another door.

Then we were on the roof.

Copyright © 2023 Lee Polevoi.

The Confessions of Gabriel Ash, a new novel by Highbrow Magazine chief book critic Lee Polevoi, will be published this month. This excerpt, "The State Dinner," is published by permission of Running Wild Press.

Image Sources:

--Whiteghost.ink (Wikimedia, Creative Commons)

--David Guerrero (Pexels, Creative Commons)

--Anaterate (Pixabay, Creative Commons)

--Maxpixel (Creative Commons)

--Succo (Pixabay, Creative Commons)