Georgia O’Keeffe at MoMA: A Closer Look at Greatness

--All images of artworks are courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art Press Office (see here.) Top image: Georgia O’Keeffe. Evening Star No.III, 1917. Watercolor on paper mounted on board. 8 7/8 x 11 7/8″ (22.7 x 30.4 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Mr. and Mrs. Donald B. Straus Fund, 1958. © 2022 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Defining greatness can be a dangerous thing. The public likes its celebrities—whether in the art world or the concert stage—signed, sealed, and delivered, the glossier the package the better. In O’Keeffe’s case, we get artist as hermit, a female legend who weathered well in the New Mexico sun over her 98 years, giving us cow skulls and closeups of erotically suggestive flowers that if they didn’t calcify her fame, cemented her reputation for all time.

Thanks to the current MoMA exhibition, there’s another O’Keeffe worth considering. This one is spirited, intuitive and filled with a wanderlust that serves her burgeoning young talents well. From her early days on Wisconsin farmland—a high school stint in Virginia, followed by the Art Institute of Chicago and the Art Students League of New York, and a summer at Lake George, camping trips in Appalachia, and teaching stints in Texas and South Carolina--she was endlessly experimenting.

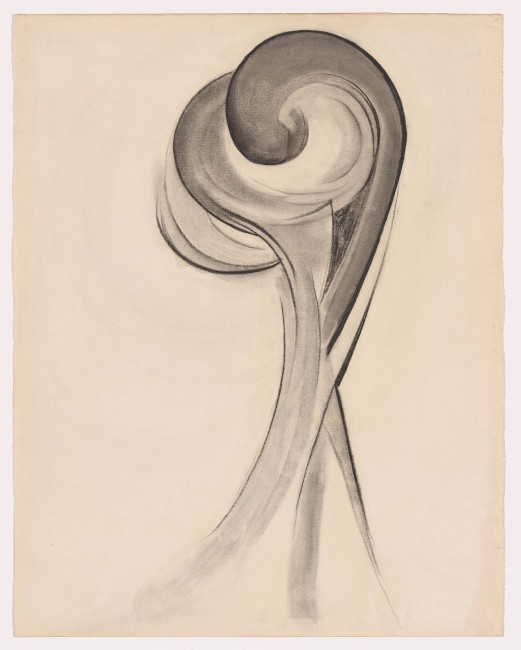

Georgia O’Keeffe. No. 12 Special, 1916. Charcoal on paper. 24 x 19″ (61 x 48.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation, 1995. © 2022 The Museum of Modern Art / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Over 120 works, including examples from MoMA’s collection, demonstrate the ways in which O’Keeffe developed, repeated, and changed motifs that blur the boundary between observation and abstraction. And many of these works were completed by 1917, the year this fledgling artist turned 30.

Primarily works in graphite, charcoal, pastel, and watercolor dazzle the eye and demand a closer look. O’Keeffe was a natural colorist and Red and Blue No. 1 (1916) demonstrates a clash of color, the shocking prominence of shape confronting the viewer. No subtle depiction of subject here.

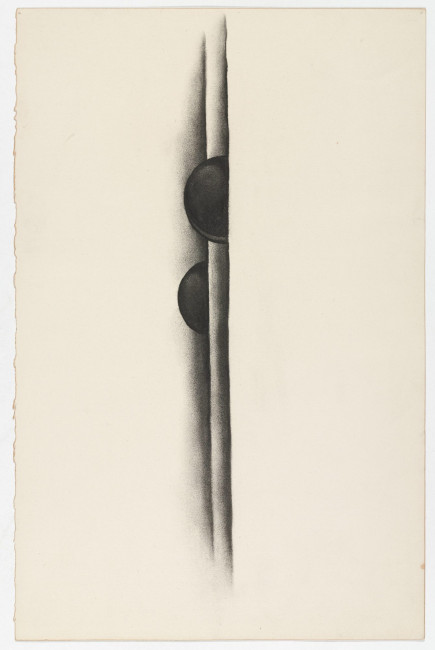

Georgia O’Keeffe. Special No.39, 1919. Charcoal on paper. 19 5/8 x 12 3/4″ (49.8 x 32.4 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation, 1995. © 2022 The Museum of Modern Art / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The same year, she exhibited at Alfred Stieglitz’s gallery “291” that became a paeon to modernism. One critic said he had never seen “a women expressing herself so frankly on paper. Her “burning watercolors” from Texas wowed the other members of the Stieglitz circle. Stieglitz named her the “spirit of 291” and fellow members Arthur Dove, John Marin, and Marsden Hartley were quick to agree.

The shifts in her moods played out in an almost lyrical sensuality. Special No. 9 (1915), charcoal on cream paper, is titled Drawing of a Headache. One can feel the persistent tension, the onslaught of pain, like punctures in the brain. A series created during a camping trip, Tent Door at Night demonstrates an early obsession with detail that meets abstraction on its own terms. What exactly are we seeing?

Georgia O’Keeffe. It Was Yellow and Pink III, 1960. Oil on canvas, 40 × 30″ (101.6 × 76.2 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. Alfred Stieglitz Collection, bequest of Georgia O’Keeffe. © 2023 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Composition, scale, and color have equal play in House with Tree-Green from 1918. It’s a hypnotic image, demonstrating an almost childlike treatment of her subject. The oversimplification of subject matter did not go unrecognized by Stieglitz as mentor and later husband. He was enthralled by what he saw as her unconscious, given full play in her art, and saw her persona, for better or worse, as exemplifying the woman-child. These “songs of herself” she saw as being “as much yours as mine.” But it was a complicated union. Hers was a special power of sight enriched by her own womanly eroticism -- a pure, natural sexuality opposed to bourgeois repression.

Music played an ever-present role in her creations. “Words and I are not good friends at all,” she admitted, so she said she slaved away at the violin instead, trying to find its voice. Early teachers encouraged her to listen to music while composing her drawings, and she was receptive to that advice.

Georgia O’Keeffe. Over Blue, 1918. Pastel on paper, 28 × 22″ (71.1 × 55.9 cm). Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester. Bequest of Anne G. Whitman. © 2023 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Her mastery of watercolor is on display in a series of nude self-portraits from 1917. The spontaneity and pooling of paint is remarkably fresh, especially considering she was alternately twisting herself about to get what she said she couldn’t get any other way.

There are examples of her pastel work from 1922 that dramatize her fascination with nature at its most compelling. Lightning at Sea is filled with the gorgeous starkness she brings to her subject, admitting that “the skin is wearing off my fingers from rubbing.”

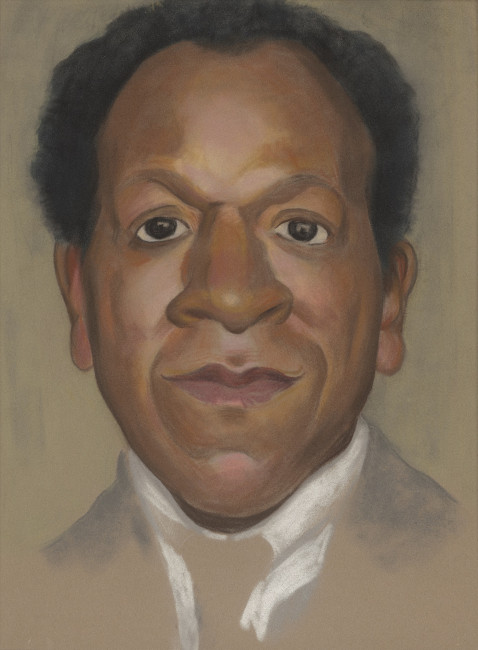

Georgia O’Keeffe. Beauford Delaney, 1943. Pastel on paper, 15 1/4 × 11 1/2″ (38.7 × 29.2 cm). Myron Kunin Collection of American Art, Minneapolis. © 2023 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Portraiture was not her strong suit, but her head portraits of her friend Beauford Delaney show an adeptness at creating such images if she was sufficiently persuaded.

Moving permanently to New Mexico in 1949 after 20 years of summering in her chosen home, she still felt the stirrings of wanderlust. Peru beckoned in 1956 and a trip around the world in 1959. These shifting perspectives of being in the air and on the ground appeared in later works, such as It was Yellow and Pink II (1959).

Georgia O’Keeffe will undoubtedly continue to fascinate her viewers. Perhaps this exhibition will help her audiences recognize the importance of not pigeon-holing, such a prominent American painter recognized for her most popular images, but to look instead at the richness and diversity of a work of a lifetime.

Georgia O’Keeffe. Seated Nude XI, 1917. Watercolor on paper. 11 7/8 × 8 7/8″ (30.2 × 22.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Purchase, Mr. and Mrs. Milton Petrie Gift, 1981. © 2023 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

--Cover photo of Georgia O'Keeffe: Source: Phillips. Author: Alfred Stieglitz (Wikimedia.org, Creative Commons)

Author Bio:

Sandra Bertrand is Highbrow Magazine’s chief art critic.

For Highbrow Magazine