On Your Radar: Highlights From the Art World

Faith Ringgold: American People

Recognition for some is like being in the center of a floodlight, instantaneous and often too bright to withstand for long. For others, fame can feel like a lucky penny, found in the sidewalk crack after a long rest.

For artist Faith Ringgold, there was no rest. If she was under the radar for many, she kept creating, drawing from personal autobiography and collective histories to both document her life and to illustrate the struggles for social justice and equity.

“Faith Ringgold: American People” at NYC’s New Museum is the most comprehensive exhibition to date of this groundbreaking artist’s vision. And for this visitor, it was an eye-opening revelation. From bold, politically charged paintings in a graphic style she called “super realism” to her famed and inflammatory story quilts, she has remained an unstoppable force of nature.

In 1963, when Ringgold began her American People series, her idea was to make art about what was happening to Black people at the time. Between Friends, the first in the series, represents a Black and white woman, inspired by liberal-minded women she met on Martha’s Vineyard. The narrow space suggests a close but tense intimacy. Delicacy has no place in this stark dramatic portraiture.

Also on view is her U.S. Postage Stamp Commemorating the Advent of Black Power. In this repetitious grid, she has concealed “Black Power” and “White Power” amidst the tiled Black faces. When this, along with other murals was shown at the Spectrum Gallery in 1967, it was her first exhibition outside of Harlem. Ringgold was the first Black artist on the roster.

But Ringgold was not content to put her spin on America alone. Traveling to Paris as a single mother, she placed an uncompromising eye on the male painters who had risen to the heights of the public pantheon. In this first full presentation of her French collection in decades, viewers can delight in picking out Picasso himself in her revisionist take on his Les Frommes Demoiselles d’Avignon masterwork.

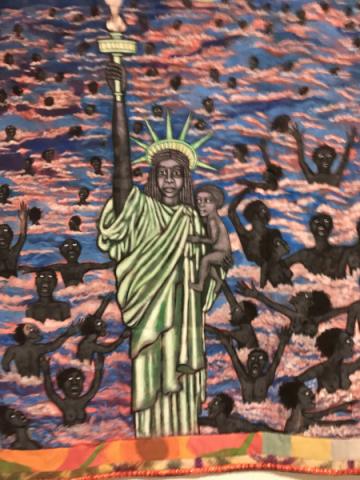

The first in her American Collection series of story quilts from 1997, We Came to America #1, the Statue of Liberty stands with a naked child in her arms. Surrounded by flailing Black slaves from a burning ship, it puts front and center her version in response to a more polite and purist take on our turbulent history.

Jean-Michel Basquiat: King Pleasure

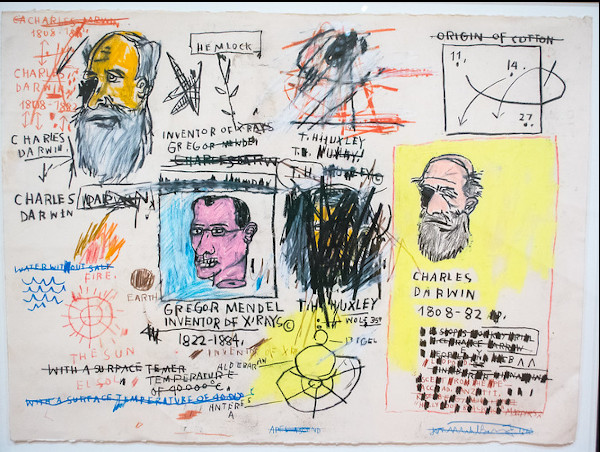

To say that Basquiat’s rise to fame was meteoric is an understatement. This Black Pop culture icon, dead at 27 from a heroin overdose, was catapulted to fame in the 1980s by his version of rap, punk street art, coupled with a nascent talent to perfectly interpret his times. Befriended by media star Andy Warhol, he was his own man in that glittery firmament. According to his younger sister Lisane, he was “huge energy entering this world.”

The current exhibition, curated by sisters Lisane Basquiat and Jeanine Heriveaux, is an over-the-top, rich pastiche of the artist’s brief life. Housed in the Starret-Lehigh building in Chelsea, it features over 200 artworks and artifacts from the artist’s estate – 177 of which have never been seen before. It was five years in the making, and though the sisters are admittedly not curators in the traditional sense, they have given the public an amazingly detailed, close-up glimpse of his life.

Ambling through the 15,000 square-foot space, the viewer encounters a scrapbook redolent of domestic life in Brooklyn (spice racks and fish platters notwithstanding); his studio at 57 Great Jones Street and the Michael Todd VIP room at the Palladium, complete with mirrors and candelabras. Soundtracks add their own ambiance, with “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough” by Diana Ross to entertain you during your wanderings. I’ll leave it to the visitor to decide whether these kitschy environments are clues to the explosive artistic output Basquiat left behind.

The artworks are definitely capable of speaking for themselves. The 41-foot-wide Nu-Nile, created for the Palladium nightclub in 1985 will certainly bring in millions for the estate, managed by the two sisters and their stepmother, Nora Fitzpatrick. Though exhibit offerings are not for sale, Phillips has a $70 million auction price set for a “Devil” painting from 1982, and his skull painting sold in 2017 for a record-shattering $10.5 million. The Broad Museum in Los Angeles and the Orlando Museum of Art both have exhibitions running concurrently.

Profit clearly plays its hand with $45 timed tickets sold online and a King Pleasure Emporium where leather goods, athletic wear, and housewares are available for sale. But make no mistake: Jean-Michel Basquiat was an avatar of his generation and will probably continue to be for decades to come.

Our Selves: Photographs by Women Artists

Carrie Mae Weems, one of the more celebrated women photographers in MOMA’s current exhibition, challenges the viewer with the following question: “In one way or another, my work endlessly explodes the limits of tradition. I’m determined to find new models to live by. Aren’t you?”

The truth is, women photographers have been exploding expectations for decades. Their work has simply been under the radar for far too long. This exhibition, through Helen Kornblum’s generous gift, proves that women can carry the demands and diversity of the profession. From portraiture, photojournalism, social documentary, avant-garde experimentation, advertising, and performance, the proof is here in every image encountered.

Portraiture, both timeless in intent as well as in contemporary in-your-face style, is immediately evident. Sharon Lockhart’s untitled chromogenic print from 2010, gives us a young woman absorbed in the puzzle before her. It is reminiscent of a Dutch Renaissance masterwork. The serenity and beauty of the composition appeared at my viewing to have a magnetic draw on onlookers.

Mary Ellen Mark’s Tiny, Halloween, Seattle, (1983) combines insolence and innocence. This is an adolescent who will not just “sit pretty” for the camera. Mark’s mastery in capturing ordinary Americans could stand beside Robert Frank’s iconic fifties portraiture any day. There are other examples that resonate, such as Catherine Opie’s Angela Scheirl (1993). The subject we are told is a member of Opie’s LGBTQ community—confident in her male attire; confident as well in her act of becoming her new moniker, Hans. Hullea J. Tinsinhnahjinnie is a Native-born Navajo artist who has chosen to reinterpret images of Native peoples. In Vanna Brown, Azteca style (1990) she has surrealistically recast the Wheel of Fortune game show hostess Vanna White as an indigenous woman shining forth from a TV screen.

In this writer’s opinion, the power of black and white, and the countless shades of gray that lay between the ends of the spectrum are the greatest challenges in photographic art. It can also provide the greatest awards to those who persist. A lesser-known photographer, Consuelo Kanaga, gives us a little Black girl in profile. Immersed in her thoughts, the whiteness of her uniform blouse and her wide-brimmed straw hat contrasting with her small dark limbs, speaks volumes about her silent isolation.

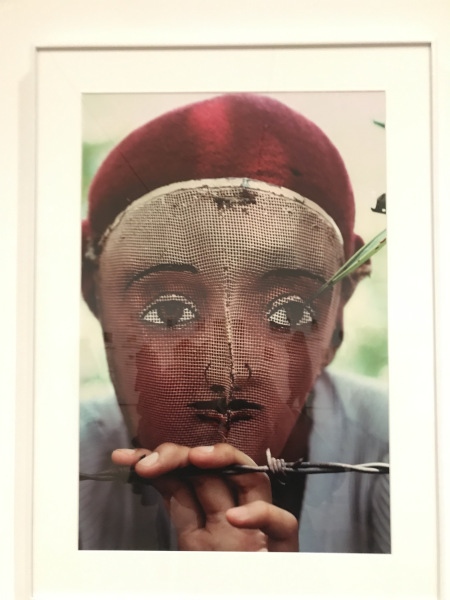

There are many others, such as the great Dorothea Lange, who shows up her great portraiture in one of the vitrines of letters and publications on display. Susan Meiselas, an intrepid photographer of foreign shores, gives us a traditional mask used in the Popular Insurrection, Monimbo, Nicaragua from 1978. Both these photographers have shown that a social conscience is often inherent in the female gaze.

Author Bio:

Sandra Bertrand is Highbrow Magazine’s chief art critic.

For Highbrow Magazine

Image Sources:

--Sandra Bertrand

--Tim Evanson (Flickr, Creative Commons)

--Rocor (Flickr, Creative Commons)