Environmental Collapse and the Future of the Planet Hang in the Balance in ‘Orphans of Canland’

It’s sunny, the sky’s vibrating like it can’t wait, and AB’s face is split with laughter. Then the clouds move in and AB’s laughter turns to shaking worry. The yellow light turns white and AB starts to cry. Their tears become rain. The light dies. I put my face to theirs so they’re all I see. Their face is pressed against mine, and they’re calm like a baby. I try to speak, to apologize, but I have no voice. They start to pull away, their face happy, then unhappy. So I wake up. It’s like something has slipped from my grasp, a word I can’t recall.

I get up. I put on two pairs of socks and two wool sweaters and pop my teeth in and then without thinking, walk through the near-total darkness to my door, somehow not knocking anything over. I have no idea what time it is. The whole house is dark, but the path from the hall to the front door is easy because there’s nothing in the way.

It’s strange—walking through our house, without entering his room, you’d never know that Dylan lived here. There are no shoes by the door, no book on the couch, no uncleared plate on the table. We once shared my room, when Michael used Dylan’s current room exclusively as his office. Dylan and I slept in separate beds against opposite walls, and he’d talk to me until I fell asleep, asking me what I liked and thought and wanted, and telling me that one day he would invent a new species of plant through cross-pollination and genetic modification that needs no water and grows quickly and is edible to humans and poisonous to vermin, and makes Canland’s ecosystem utterly incorruptible. When he got kicked out of school, and Michael started teaching him, Dylan spent all his time in what’s now his room, and he never slept in mine again.

It’s cold out, as usual, in the desert night. I sit on the front step. I rarely go outside after dark. The sky’s full of stars that make visible silhouettes of everything—the tall, tall eucalyptus trees across the road, showing night between their leaves, soughing in a light wind that, before the trees were here to cut it up, howled tempestuously; the jagged sierras, sculptures made by ice and heat and unthinkable pressure, like stacked bones of beasts buried in the Earth; and above those peaks, a full huge pale stony moon hangs like a clock, in perpetual motion relative to us so it only ever shows one face to the Earth, a likelihood so infinitesimal that I wonder for a moment, as Michael might, who placed it there just so. Maybe scientific singularity is an argument for god, and that’s why ancient civilizations worshipped the cosmos.

![]()

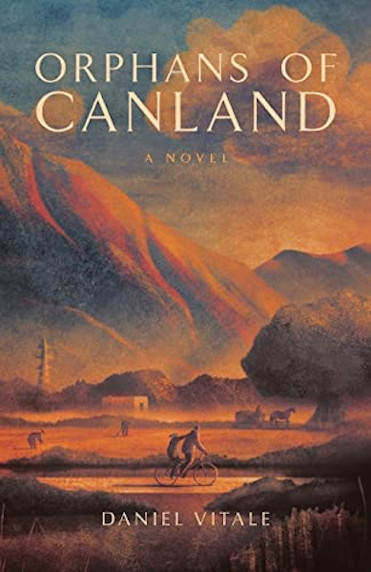

This is an excerpt from Daniel Vitale’s new book, Orphans of Canland (Strij Publishing). It’s published here with permission.

Highbrow Magazine

Image Sources:

--the Author

--Strij Publishing

--Bitmatrix (Pixabay, Creative Commons)

--Foto Rabe (Pixabay, Creative Commons)