‘Bros’ and the Legacy of Gay Cowboy Movies

Opinion:

I have a confession to make: I don’t like Billy Eichner. As a New Yorker and a homosexual, I understand this may be akin to sacrilege. There is no specific reason for my derision, either; or perhaps there are too many tiny ones that they all just evade me and I don’t have the wherewithal or desire to try and find them. It’s the same way that people seem to dislike Anne Hathaway. She’s never done anything remotely cancelable, and Mr. Eichner has never wronged me in any way, but here we are.

Eichner is measurably funny, his political views probably align with mine, and he loves musical theater. By all accounts, he should be one of my favorite celebrities. He even just co-wrote and starred in a historic queer movie: Bros, the first gay rom-com produced and distributed by a major American studio released in theaters.

But indulge me, for here is a quick and unbiased review of Bros by a casual moviegoer: the movie is fine. It’s pretty good, actually. Its title is silly and uninspired, but it is uproariously funny at times; sweet and moving at others. As a rom-com, it delivers exactly what it promises: a funny meet-cute, a journey of romance with hijinks in the mix, and a happy ending. What wasn’t so good was the movie’s attempt to paint itself as the pinnacle of queer cinema, or at least as the obvious endpoint after a long history of failed, straightwashed past gay movies in the mainstream.

Bros worked best when it leaned into the parody of queerness. One of the subplots revolves around the upcoming opening of an LGBT history museum in New York City. Jim Rash’s character calls for an absurd hall of bisexuals from throughout history to be part of the museum, complete with animatronics. Miss Lawrence’s Wanda speaks in empty platitudes about finding space for others, seeing them and understanding them, with solemn eagerness and conviction. Bowen Yang demands a ride be built at the museum that takes passengers through the stages of queer trauma, cackling evil laughter and all. This is when the comedy of the movie feels like it was made with a wink for its queer audience. It knows the ins and outs of queer experiences, the rainbows of personalities and values that pervade throughout the community, and it’s making fun of them because, well, it’s a comedy and it needs to make us laugh. When it does this, the movie laughs with us rather than at us. I mean, the movie invents a gay dating app called Zellweger for gays who want to talk about actresses and go to bed, which is utterly, stereotypically ridiculous and that’s why it’s hilarious.

But during the times that it takes itself too seriously, trying to prove that it can be a comedy and a romance and a commentary on rainbow capitalism all at once, the movie fails to make any observation that is poignant or even funny, like when it constantly calls out the failures of queer cinema past. This is mainly due because the only commentary it seeks to make on its predecessors is that they were all, supposedly, somehow less queer than Bros. It just comes across as mean-spirited then, or like it missed the point of that queer cinema history it tries so hard to troll, however flawed and ugly that history may be.

There’s a running gag in Bros about gay cowboy movies. There’s even a fictional gay cowboy movie currently playing in theaters in the Bros universe, one that’s critically acclaimed and movie buffs and snobs are pouring into the multiplexes to see (the irony of this in hindsight is not lost, considering Bros performed poorly at the box office). Perhaps this is the point the movie was trying to make, evidently trying to draw parallels from what it considers less queer and straightwashed gay cowboy movies that appear to have overtaken queer cinema, and the gay sex rumpus that is Bros with its mostly LGBT+ cast as a movie that is, you know, not “fake queer.”

But, undoubtedly, there are several direct lines we can draw that will connect Bros to different annals of queer film history. Like from the decidedly non-queer movies that have since been claimed, such as horror films spanning from the monster flicks of the 1930s, through the suspiciously glossy vampires of the 90s and aughts, right in the middle of the Chucky and Hellraiser franchises, to the indie spooks the likes of Hereditary.

There are also, of course, the explicitly queer movies that have been around since before Eichner had even been born. The Detective, for example, is one of the first movies to have confronted taboo subjects in mainstream media, where Frank Sinatra plays the titular sleuth caught up in a case in the seedy homosexual underworld of New York City. Arguably archaic by today’s standards, and even a bit overdramatic with its depiction of homosexual stereotypes, the film nevertheless brought forth to the mainstream the concept of homosexuals as, basically, just another type of people that exist. This was a year before the Stonewall riots. (Interestingly, the books The Detective was based on would span the widely successful and testosterone-fueled Die Hard films. There is a gay joke in there somewhere about a man walking around a high-rise barefoot and in a tight tank top). Or there are films more in the vein of Bros, like Parting Glances, a bittersweet rom-com about a man looking after his dying ex-boyfriend while his current boyfriend plans to take a job across the world.

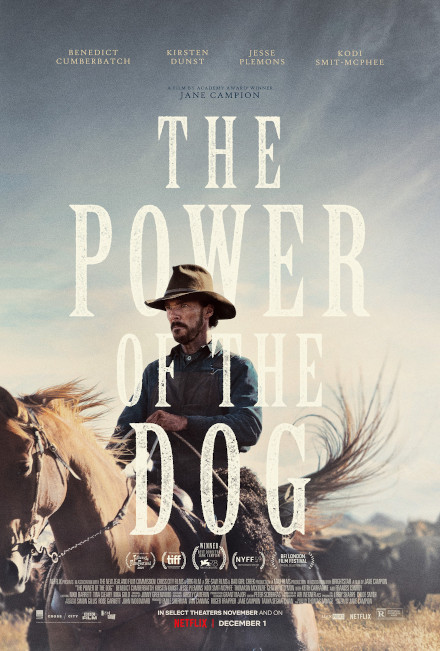

And unfortunately for Eichner, no modern queer movie can go untethered to the much-maligned genre that Bros scorns: the gay cowboys movie. Certainly, to call it a “genre” is an exaggeration, hard as Bros may try to have us believe that we are inundated by gay cowboys (wouldn’t that be nice?). The movie appears to take aim at the two best-known cowboy movies that feature a queer theme: Brokeback Mountain and the more recent The Power of the Dog. Though the latter makes the characters’ queerness clear within the subtext, it doesn’t actually feature any same-sex affection. Besides, assessing it by the same standards with which Bros marketed itself, The Power of the Dog wouldn’t even count as a major release, since it was made and distributed by the indie, obscure arthouse known in movie circles as Netflix. While Brokeback Mountain, whether we like it or not, was a floodgate that opened the way for modern queer cinema and changed the landscape for independent American filmmaking.

That said, there is a veritable tradition of queer visibility in cowboy movies since the inception of the westerns. It makes sense. The signifiers of manhood that westerns profess lend themselves neatly to subversive readings, be it of masculinity or gender roles or sexual desires. There’s also something inherently homoerotic about the rugged manliness in display, awash in buckskins and muddy shirts with open collars and the need for release. Like in football. Or wrestling. And other contact sports that favor bigness, with body parts constantly pulsing and pushing against each other and codpieces in full-on spectacle. All characteristically manly things. It’s the kind of subversion that Andy Warhol satirized in 1968’s Lonesome Cowboys.

Some westerns were made queer, almost certainly, by accident. Or at least with no explicit intention of making them gay. This is true of the gold standard of westerns Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Led by two of the handsomest men of the era, the sexual tension between the titular characters both with each other and with Etta, the female lead, makes any queer person watching the movie patiently wait for Butch and Harry to walk off into the distance holding hands while taking turns kissing Etta, because this was 100 percent a polyamorous lovefest. In a way, we get a bit of that sexual release in the final shootout, when Butch and Harry pull their guns out and then leave us in suspense with that freeze frame.

Others were made with a more tongue-in-cheek gaiety. Like Calamity Jane, with Doris Day singing about her secret love while frolicking around the grass in a bow-tied button-down. Or Johnny Guitar, with lesbian undertones to rival the sexual tension of Butch Cassidy. Directed by bisexual director Nicholas Ray, Johnny Guitar sees Joan Crawford genre-bending the westerns by playing “a woman who was more of a man” caught up in a rivalry with Mercedes McCambridge. (Ray would go on to direct Rebel Without a Cause, a bisexual cult favorite). And all the way back in the 40s, critically beloved Red River saw John Wayne opposite Montgomery Clift in his film debut. Clift—one of the most beautiful men to have graced our screens, in my humble opinion—in a now infamous scene, whips out his gun to compare it with John Ireland’s, feeling the weight of each other’s piece and singing each other’s praises as to how well they shoot. The imagery is unmistakable. In many ways, it’s even joyful and courageous, considering that Clift, notoriously secretive and ambiguous about his private life, was homosexual and had long-term relationships with men throughout his life, though we only learned about his homosexuality after his death.

All this may be what is often lost when approaching queer cinema history with a single-lens focus on superficiality, like Bros does. The context of who made these films and within what circumstances is all part of what ends up on the screen. We can look at the choices filmmakers and artists made in the past and see how, whether through coding or allegory, they depicted a queer experience that was still easily deciphered by queer audiences watching.

Nicholas Ray couldn’t explicitly depict a same-sex romance on screen at the time Rebel Without a Cause was made and released, but the bisexual subtext that permeates throughout the film would not have been seen as anything other than that by today’s critics. Meanwhile, Hitchcock coded the infamous Mrs. Danvers as a grief-stricken lover lamenting the loss of the titular character in the 1940 classic Rebecca, whether to paint her as villainous or to provide depth to her suffering character (though more likely the former; in fact, Hitchcock employed this tool of queer subtext in several of his movies to depict villainy).

When Gore Vidal wrote Ben-Hur, he infused it with queer love within the subtext of one of the movie’s core relationships between the titular character and Messala, his childhood best friend who eventually betrays him. This caused a bit of stir when, decades later, Vidal himself confirmed that the character of Messala had indeed been written to suggest a prior sexual relationship between the two men; and that Messala, in fact, was likely still in love with Ben-Hur when they reunite in the movie. To queer audiences who watched the movie, this wasn’t a shocking admission as much as it was a redundant confirmation of what was so clear on the screen. The imagery and the underlying theme of Ben-Hur and Messala’s relationship was crystal clear as an allegory to those who understood the code. The 2016 remake of the epic was devoid of this queer undertone. When asked about it, the actor playing Messala replied that it was understandable that the famous 1959 version included that queer subtext between the men, as it was the only way that a queer voice could be somewhat represented in those times, but that we have since moved on from that and no longer need that kind of esoteric representation, presumably because we can now have “real,” explicit representation. Blindness to the actual state of things aside, it was a nice sentiment. But it misses the point.

Because of this long and grand tradition of queering movies since movies have existed, queer subtext is just another type of film language. Just as there are ways, for example, to hit certain narrative points or use a specific archetype character to indicate that we’re watching an action movie, or a noir thriller, or a romantic comedy, so too exists a way to create a queer language in a film. And just like any film language, this is meant to be more subliminal than explicit, with the use of lighting and sound and narrative points and tropes and queer signifiers to instill the audience with feelings or vague understandings of what we’re watching: not quite out of grasp, but more like trying to grasp at smoke. Filmmakers know how to do this because queer subtext in films has an extensive and rich history, all the way from Dracula’s Daughter in the 30s to last year’s The Power of the Dog.

When done well and with intent, the film language of queerness can be used for effective messaging and a wink to a queer audience. This is why many would posit that A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge is a much gayer movie than, say, The Imitation Game. The latter was a sanitized snapshot of a gay man’s life devoid of any actual gayness; and any homosexual subtext that existed was to make him a weird and off-putting oddball like all geniuses must be, not to actually make him seem gay. Seed of Chucky probably has a more honest, albeit gory, take on non-binary gender roles and transgenderism than the movie musical Rent. In fact, the murderous doll created by Don Mancini, a gay man, has long been a queer ally.

This is not meant to give movies that eschew representation an all-out pass. Instead, while all the subliminal representation in the queer subtexts should be celebrated, identified, and continued to be claimed when it is done as a form of film language, it can also be used to be a roadmap that traces all the queer landmarks that have come before, from the breadcrumbs to the lighthouses: we needed Cat on a Hot Tin Roof with its very dampened queer subtext to get to Parting Glances.

Yes, Parting Glances dealt with AIDS and that can be a downer (another AIDS movie!?). But Parting Glances had the incredible bravery of existing in the mid-80s, having a frank depiction of AIDS and its effect at the height of the pandemic and in the face of the Reagan administration’s inaction: only five months prior to its release, Reagan finally said the acronym AIDS. It’s a bittersweet rom-com gorgeously written and directed by Bill Sherwood, a gay man himself who would die of AIDS before he could make another film. We cannot separate AIDS from this movie, and yet it is a romantic comedy.

“Robert was moving to Africa,” says the steely-voiced narrator in the movie’s deliciously 80s trailer. “Michael was hating him for it. And Nick was dying of AIDS.” Very casual. The movie is witty and sad and superbly funny all at once. And truth be told, straight and all, Steve Buscemi was the absolute perfect casting choice. An up-and-coming unknown then, he plays Nick, the hapless, dying ex-boyfriend. Nick is a firecracker, droll and snarky and kind. Dealing with his illness while still living his life. The movie’s portrayal of everything that was awful then, told through the unconventional concept of comedy for this topic, is brilliantly realized. It’s outrageous and courageous, and so very queer.

We needed Parting Glances to trek over to Philadelphia (yes, yes, yet another AIDS movie). Philadelphia shies away from depicting homosexual affection, even though gay sex must be a central theme of the movie. It explicitly cowers from showing signs of homosexual love, almost certainly to try to not alienate straight audiences, and there is not a single openly queer main actor in sight. But Philadelphia did give us Tom Hanks. Straight, dependable, respectable, universally beloved Tom Hank playing a gay man. This may not have been ideal, but it was important and necessary. It’s one of the pitstops we needed to make to eventually, finally make it to the watershed that was Brokeback Mountain.

I have another confession to make: I love Brokeback Mountain. As a film in itself, it is gorgeously filmed, well-acted, and heart-wrenching in a way only a movie can be. I’m not blind to its flaws. It’s led by two straight actors, directed by a straight man, and for all intents and purposes made with a straight audience in mind. It doesn’t have a happy ending, and queer violence is an important plot point. I don’t even like Jake Gyllenhaal (after some introspection, it appears that no logical reason exists for this either). But Brokeback was also the first queer movie that I watched and that I understood was the beginning of something, even if I didn’t fully grasp the enormity of it. Because the truth of the matter is that Brokeback Mountain did begin a new legacy for queer filmmaking.

Interestingly, Lee Daniels, of Monster’s Ball and Precious fame and a gay man himself, was slated to direct Brokeback Mountain at first but could not find a way to fund it. He later said that he was unable to watch the movie for many years because he had his own vision for it that he couldn’t shake. He acknowledges, once he’d seen it, that Ang Lee made a good movie even if the movie was made through a straight lens, and also concedes that this was probably, for better or worse, a good thing. The film needed the star power of Gyllenhaal and Heath Ledger, and the poignant performances of Michelle Williams and Anne Hathaway. It needed to be a mainstream vehicle to reach a wider audience and an indie awards darling. And perhaps above all, it needed to be a universal story; a good ol’ story of forbidden love in trying times. This isn’t necessarily a good thing now. The universal appeal served its purpose when the times required it. And now we can have stories that are not heterocentric – which is to say, stories that don’t place heteronormativity as the center of origin from which everything else branches out. Bros actually makes an admirable attempt at this. It’s a by-the-numbers rom-com, sure, but it’s not just a remake of myriad straight romantic comedies that merely swaps its female lead with a hunky/sensitive lawyer. It tries to layer it with shades of queerness that can only exist in a non-heteronormative story.

Yet, all this doesn’t make Brokeback Mountain a “fake” queer movie. The book The Power of the Dog was based on was written by a homosexual man who was closeted at the time. With this knowledge, it’s impossible not to see and appreciate the subliminal messages in The Power of the Dog that deal with suppressed sexuality during a time and place when rigid signifiers of manliness was the norm and expected. Annie Proulx was directly influenced by The Power of the Dog when she wrote the short story that would become the landmark movie that Brokeback Mountain turned out to be.

And it’s almost certainly thanks to Brokeback that we have myriad of new queer classics now. From Love, Simon, to Carol, to Happiest Season, to the recent Fire Island. Bros may mistakenly consider these films somehow lesser. This, even though Happiest Season was actually meant to be the first gay rom-com produced by a major studio and released in theaters before it was moved to streaming because of the breakout of COVID; and even though calling Hulu or Netflix minor studios at this point is dubious at best. But they are all just trying to be the next Brokeback Mountain. As they all well should. Because to be sure, there will come a time when a newer, fresher, better, mainstream queer film—from a “major” studio because let’s not forget that the cultural milestone that was Moonlight already exists—takes its mantle, and when that happens, it will be a time for celebration. Bros tried it too, and its attempt was commendable. It’s too bad that the film is just not it, even though I can be and am glad that Bros exists.

Author Bio:

Angelo Franco is Highbrow Magazine’s chief features writer.

For Highbrow Magazine