Families Break Apart Amidst Raging Conflict in Gripping WWII Novel

(Photo credit: Depositphotos.com)

Families kept piling in. One after another. The area the Japanese had cordoned off for the internment camp didn’t have enough space for the number of people who kept arriving.

On the march, she’d seen the Slingerland family and the Van der Hurk family, but she didn’t know where they had ended up. The guard led Mary and her family to a small house with a yard and fence, then ushered them toward the house. One side of the yard was dug out for a garden, although it looked as if it had been trampled recently. The house was a decent size for a family home, but not for the masses of women and children crowding inside the camp. With her family, Mary lugged their belongings up the steps of the veranda then stepped inside.

Chaos ensued, with people staking their claim to rooms or spots on the floor. Two women argued over one of the bedrooms. Tie moved quickly ahead with her single suitcase, not stopping to help Mary with the rest of their stuff. She stared at the place in disbelief. The home had probably once been functional, but the belongings had been gutted, and it was crammed with a mishmash of people and things.

“Leave the windows open,” a woman called out as another woman shut the windows in the kitchen.

The second woman said something in a much quieter voice, and the first woman said, “Air and heat is better than no air at all.”

“Come on, children,” Mary muttered. She maneuvered their cot along the hallway until they reached a small room that might have once been a study. There was a desk and chair shoved into the corner, and two beds. A bookcase stood in the corner, and on one shelf was a worn pile of books. Otherwise, it was empty of memorabilia that might have once been stashed there. The door was missing to the study, and to all the other rooms as well. That wouldn’t afford much privacy.

“Let’s take it,” Oma said. “There might not be anything better.”

Mary entered the room, and they all set to work. Even though her hands were busy, her mind worried. At least they had given their names when they’d arrived at this place. That meant there would be a record of them, and George could find them when he returned. Right?

She and Oma set up the cot. Little Georgie was already looking tired enough for a nap.

“Oh, here you are.” Tie walked in and stashed her suitcase in the corner. Then she disappeared into the hallway without another word.

Mary had no idea what to expect next, so she focused on the here and now. She opened her suitcase and told everyone to unpack and settle in. Then she made up the bed for Georgie. She turned to her mother, who looked tired as well. Her fair skin had burned in the sun, and Mary guessed they were all a little sunburnt. “Ma, can you stay with him while I go find out where we can buy food for our meals?”

“Of course,” Oma gathered Georgie close. His eyes were dropping, and he leaned his blonde head against Oma’s shoulder.

Mary hesitated, wondering whether or not to take Rita, but finally, she grasped her daughter’s hand and headed out of their room. They would check out their immediate surroundings, then find out what they were supposed to be doing and helping with.

They passed by the Vos family, who’d found a portion of dining room to share with another family.

“Do you need any help?” Mary asked.

“We’re fine,” Claudia said, with a wave of her hand. “Thank you.”

Mary nodded, then headed to the front door with Rita. They stepped onto the veranda. Johan had tied up Kells outside by the gate with a rope. Other dogs were out there, and a few people had brought cats in carriers. Mary had stayed out of the arguments of whether or not cats should allowed in the house since some people had allergies.

(Photo credit: Depositphotos.com)

Her attention was caught by a cluster of Japanese soldiers who’d gathered at the gate to the yard. They were gesturing toward a couple of boys who looked about 13 or 14, not much older than the Vos children.

One of the boy’s mothers was crying.

“What’s going on?” Claudia asked, stepping onto the veranda too, with Johan and Greta—or Willy now—at her side.

“It looks like those boys are being separated from their mothers,” Mary said.

Claudia put an arm about Johan’s shoulders and pulled him closer.

Sure enough, the soldiers led away the teenage boys, and it was then that Mary noticed the truck on the other side of the road. Several other teen boys were in the back, being guarded by the Japanese.

When the crying woman and the other mother came toward the veranda, Mary asked, “What’s happening? Where are your boys going?”

The woman with tears in her eyes looked up. “They’re taking them to a men’s camp with the other older boys. They said that our camp will be only for women, girls, and younger children.”

Mary frowned after the truck as it pulled away and headed toward the gates. More families were being torn apart. The men had already been captured and sent to camps, but who knew if the boys would be in the same camps as their fathers.

Rita tugged on her hand, and Mary looked down.

“What about Johan?” Rita asked, glancing over at her friend. “Will he have to leave our camp?”

“No, Ita.” Mary drew her daughter away from the grieving women. It wasn’t like Mary could shield her children from what was happening around them, out in the open, but she wanted a bit of a reprieve from this hard day.

Claudia followed Mary. “Let’s find out if there’s a place to get food and where we’re supposed to cook.”

Mary couldn’t imagine so many people all sharing the same kitchen in one house. There wasn’t room, and food preparation would have to be done around the clock.

In every house and yard they passed, women and children worked to settle in.

(Photo credit: Depositphotos.com)

Some had left bags and suitcases stacked outside against the houses because they’d run out of space inside. Despite all the shifting of lives, groups of kids ran around together as if their lives hadn’t been upended in the past few hours.

Mary stopped to speak with Mrs. Slingerland and asked if she needed help with her young ones. “You take care of yourself, my dear,” Mrs. Slingerland said in a silver-spoon voice, hands on her hips. “We all have our plates full. But it looks like we’re a couple of houses apart.”

Mrs. Van der Hurk joined them at the edge of the yard. At least the two women would be housemates. “Is this a dream or a nightmare?” Mrs. Van der Hurk commented. No one had an answer. She looked down at Rita. “Come play with Corrie any time.”

Rita smiled but clung more tightly to Mary’s hand. They moved on, mostly gazing about at the unbelievable situation they found themselves in. Claudia voiced several questions as they walked, but her children remained silent. Even Johan, who was usually a fountain of information or questions. His blue eyes looked about as wide as saucers as he took everything in. His sunburnt nose was close to blistering. Greta, or Willy, was naturally quiet, so her silence wasn’t anything different.

“Mary!” someone called, and she turned to see Mrs. Venema.

“Where are you staying?” Mrs. Venema asked, joining them on the road. Her youngest daughter, Ina, walked out with her.

“We’re both three houses that way,” Mary explained. “Tie is with us too.”

“Oh, that’s nice your sister-in-law is close,” Mrs. Venema said. “This camp is too small for all these people, yes?”

Mary couldn’t agree more. “I wonder how many more people they’ll allow in?”

Mrs. Venema sighed. “I’ve been told that the eastern boundary is the drainage canal, the northern is where the marshes are, and the southwest boundary is the railway line.”

“So the camp is shaped like a triangle?” Claudia interjected.

“Correct,” Mrs. Venema said. “Be grateful we’re not assigned to the northwestern portion of the camp.”

She didn’t need to say more. All the women knew its reputation for being a red-light district.

Then Mrs. Venema peered at Greta. Her brows lifted as she put two and two together. “Haircut?”

“This is my son Willy,” Claudia stated.

Greta’s face flushed, and Ina stared, questions in her eyes.

“Ah, I understand,” Mrs. Venema said. “I won’t say a thing.”

Claudia gave a stiff nod.

Mary wondered if Mrs. Venema thought Claudia had taken drastic action about her daughter, but even so, the Venema girls were older, and it would be much harder to hide their gender. To change the focus, she said, “We’re going to find out what the food situation is.”

“Why don’t you go with them, Ina,” Mrs. Venema said. “Report back here. I’ll finish setting our things up.”

Ina joined their group as they continued down the road. She and Greta walked toward the back, talking quietly.

Mary scanned those they passed along the way. More refugees kept coming, led by Japanese soldiers who took them to where they’d have to set up. There were no Dutch men in sight.

“Not all soldiers are Japanese,” Johan said suddenly.

It was true, Mary had observed. Some Indonesians were mixed in.

“Some are Korean,” Johan said. “I heard it on the radio report.”

“Ah, it would make sense,” Claudia said. Japan had colonized Korea in 1910, so the Koreans had been assimilated into the Japanese army.

They were nearly to the large gates at the entrance of the camp now, and Mary paused. Trucks were coming in and out, and when they did, the refugees were stopped by soldiers to let them pass. One truck was in the process of being unloaded, and the contents looked like bags of rice.

“I wonder if there’s a central kitchen?” Claudia asked, echoing Mary’s own question.

Someone yelled, a man’s voice, and Mary looked toward the gate. A family was being separated. Older sons from their mother and younger siblings.

Before Mary could usher Rita away, one of the soldiers struck one of the boys. The mother screamed.

Mary tugged Rita along with her, back the way they’d come, back to their cramped house.

Claudia hurried right alongside them.

They were all too numb to speak about what they’d just seen.

(Photo credit: Aaron Visuals, Pexels, Creative Commons)

When the houses became more familiar, Mary felt relieved to be closer. At the moment she was supremely grateful her children were young. Ina and Greta had fallen silent. When Ina broke off from the group as they reached her house, she waved, then ran off.

Even though the sun was bright and the sky a clear blue, a heaviness had settled over Mary. The reality of their situation was all around them. As they neared their assigned house, Tie hurried out and headed across the yard toward them before they reached the walkway to the veranda.

“Mary, there you are.” Tie said in a rush, sweat staining her blouse. They were all hot from the day’s procession and unpacking. It was now the time of afternoon when most people stayed inside, where it was cooler.

“When the siren sounds, it means we have to go to roll call,” Tie said. “Our house has been assigned to a specific sector.”

“Roll call?” Claudia echoed.

“The Japanese officer spoke to me—the one who speaks Dutch,” Tie said, her breathing starting to calm. “They’re visiting each home and giving out the instructions for roll call. It’s in one hour. Where did you go?”

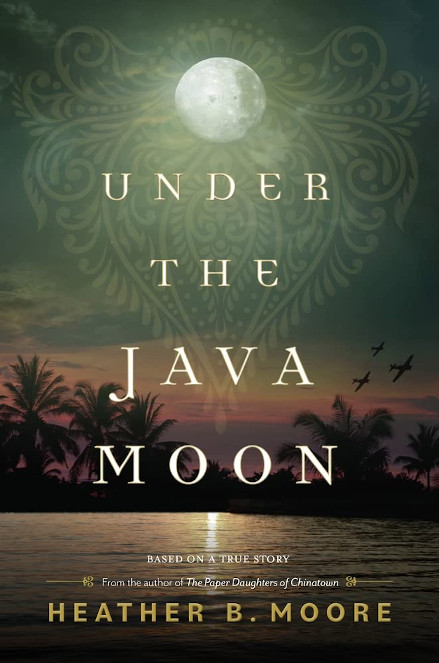

This excerpt is adapted with permission from the new book Under the Java Moon by Heather B. Moore.

Highbrow Magazine

Image Sources:

--Aaron Visuals (Pexels, Creative Commons)