Judy Chicago’s Story and More than 80 Others at the New Museum

Judy Chicago gets the bigger picture. The current exhibit Judy Chicago: Herstory at the New Museum is a testament that existence is never simply about the self, no matter how star-studded one’s role in society.

In Lauren O’Neill Butler’s excellent publication Let’s Have a Talk: Conversations with Women in Art and Culture, Chicago sustained herself by “understanding where I am and where we are in history. This isn’t about giving white middle-class career women more rights. This is about a fundamental change on our planet. And art is part of this larger struggle.”

This is a show of moving parts – the creative, ever-changing cycles of a restive, never totally satisfied artist with her successes. Through a constant exploration of mediums, she embodies the classic example of “going out on a limb” to achieve one’s aims.

After completing her B.A. in 1962 and M.F.A. in 1964 at UCLA, she enrolled in auto-body school, not surprisingly the only woman among 250 male students. The series Hoods (1964-65) shows what real talent can do with aerosolized pigments. Her embellishments included hearts, genitals, ovaries, and butterflies, to name a few. These objects became her own fender-benders to the Minimalist movement of the day.

Worth noting was her decision upon the opening of her 1970 solo exhibition at California State College, Fullerton, to change her name from Judy Gerowitz (her first husband’s) to Chicago (the city of her birth). No subtlety in this subjective switch to divest herself of names imposed through male dominance. A series of luminous round shapes, Pasadena Lifesavers in blue, red, and yellow express a growing female iconography in her work. Don’t be fooled by the titular suggestion. For Chicago, they represented the dissolving sensation of female orgasm.

Her mastery of auto-body spraying wasn’t the only male-dominated practice she embraced. Upon entering the gallery room of pyrotechnic imagery, the viewer is assailed by a series of performance works (Atmospheres 1968-74) -- photographs and films carried out using smoke machines, road flares, and the like across the Southern California landscape. In one example, Goddess with Flares, the artist has no qualms about playing with fire to reach her creative aims.

To address the marginalization in art schools many women felt, Chicago established the Feminist Art Program at Fresno State College in 1970. When it was moved to the California Institute of the Arts in Valencia, one of its groundbreaking offshoots was “Womanhouse” set in a dilapidated Hollywood mansion combining performance installation and craft techniques to express women’s experiences. A growing visual vocabulary began emerging, which is exemplified in her Through the Flower series. These acrylic sprayed canvases are stunning, boldly fashioned works that pull the viewer inside a whirling vortex of imagery. A term was developed by the group apropos of these biomorphic shapes: “central core.”

The Creation (1984) and Earth Birth (1983) are eye-catching examples of the use of fabric in quilting and weaving to achieve her ends. These were collaborations with skilled artisans to achieve the magnitude of her ends.

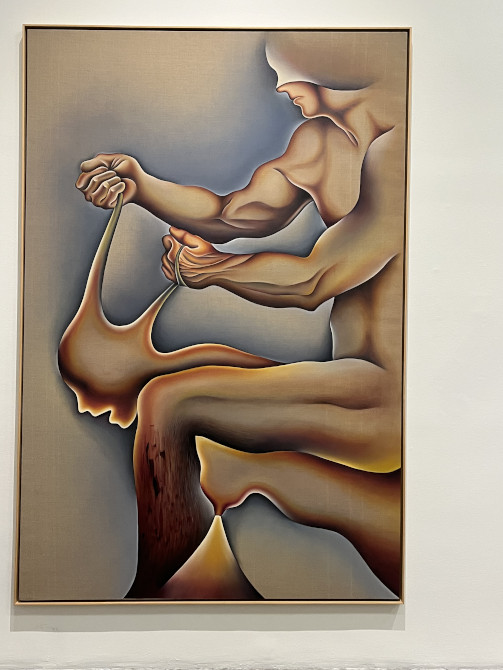

In her Power Play series, the issue of masculinity as a destructive social construct is explored. Chicago had traveled to Italy in 1982 and drawing from Renaissance nude painting, she formed a technique of acrylic underpainting topped by oil on Belgian linen, which puts her fury at male subjugation of women in full play.

If anger plays its part in some of Chicago’s most blatant imagery, the Extinction suite puts her compassion for the death of entire species front and center. Her eco-feminist view demands a close look at the brutality against nonhuman life. This is no better exemplified than in The End, a sculpture centerpiece that seems to embody mammals and sea creatures sinking into the abyss.

Such an output of subjective, yet socially conscious works seems to indicate that Judy Chicago wanted to take on the world through her art. And that’s pretty accurate. We mustn’t forget that this is the same woman who debuted The Dinner Party at the San Francisco Museum of Art in 1979. This massive triangular table of 39 place settings, each representing a historical female figure from Sappho to Sojourner Truth, created an explosive debate across the entire modern art landscape. For some critics, these vulvic painted plates were labeled as “porn” and “kitsch,” outraging the sensibilities of its time. (After decades of petitioning by legions of feminists, plus the efforts of Elizabeth Sackler and the Brooklyn Museum trustees, the work found a permanent home at that institution.)

You remember I said this was an exhibition of moving parts. No better example is this cosmos of artworks, documents, and objects from the multitude of women artists down the ages who have inspired Chicago. She has said, “If you bring Judy Chicago into the museum, you bring women’s history into the museum.” And the New Museum has done just that. Its fourth-floor exhibition space is given over to “The City of Ladies.” Many of the names need little explanation; others will be encountered for the first time. A handy pamphlet with a rollcall of bios is a take-home bonus.

In addition to an installation featuring Chicago’s own embroideries, sculptures, drawings, and carpet designs, archival materials from more than 80 women artists, writers, and cultural figures abound. From Artemisia Gentileschi to Hilma af Klimt, Emily Dickenson, Kathe Kollwitz, Remedio Varos, Djuna Barnes, Martha Graham, Simone de Beauvoir, Frida Kahlo, Augusta Savage, and Georgia O’Keeffe, the list goes on and on -- an homage to the lives of those who left an indelible mark on a Midwest girl from Chicago, a woman who has become an indisputable force for artists everywhere.

The takeaway for this reviewer is simply that this show is greater in its display of female artistic genius than the sum of its parts.

Judy Chicago: Herstory is on view at the New Museum through March 3, 2024.

Author Bio:

Sandra Bertrand is Highbrow Magazine’s chief art critic.

For Highbrow Magazine

Photo credits: Sandra Bertrand; Donald Woodman (Wikipedia, Creative Commons).