‘Labyrinth of Forms’: The Whitney Pays Homage to Women Abstractionists

Like any relationship, achieving harmony comes with its challenges. In the Whitney Museum’s exhibition, Labyrinth of Forms: Women and Abstraction, 1930-1950, 26 artists, many who remain overlooked, met the challenge head-on – pushing the evolution of abstract art in this country into the public consciousness.

Twenty-six artists and 35 works, primarily drawn from the Whitney’s permanent collection, highlight the achievements of these artists, exploring ways in which works on paper, in particular, were vital ways to experiment with a new visual language. Often relegated to the sidelines of the Abstract Expressionism movement as it grew into prominence, these women were determined to play in the big boys’ sandbox in whatever form it took.

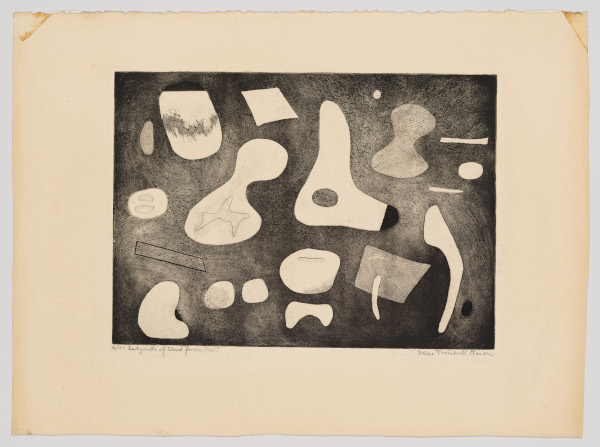

Labyrinth of Forms, a title drawn from an Alice Trumbull Mason work for this exhibition, refers to the various and innovative ways these experiments took. And Mason’s work is a good place to start. Descended from renowned history painter John Trumbull through her father, she traveled throughout Europe as a young woman, absorbing influences from Arshile Gorky’s work and support from Gertrude Stein. In late 1936, she was instrumental in founding the Association of Abstract Artists with one-fourth of its membership women.

The actual title of her etching, Labyrinth of Closed Forms (1945), belies the free-floating spirit of shapes on display. They may be “closed” in their contour but they are free-wheeling in the composition.

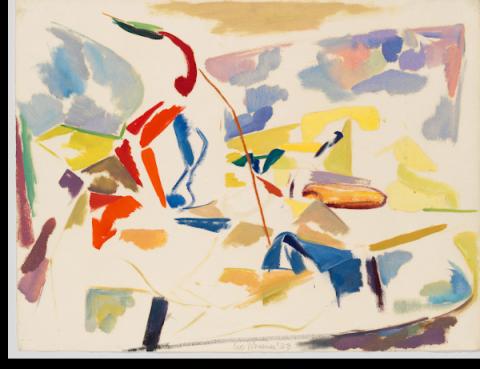

Another show inclusion that reflects the same spirit is Lee Krasner’s Still Life (1938). The influence of Hans Hoffman, the renowned early teacher and modern artist, is undeniable. He stretched the importance of negative space. Colors swirl, speeding in all directions at once in this work. The same could be said about Untitled (1942), from Charmion von Wiegand, a less celebrated painter. It’s a riotously colorful playpen of shapes, a chaotic universe but a happy one nevertheless.

Some of the early abstractionists navigated a thin line between the recognizable and the non-objective. In Anne Ryan’s Figures in a Yellow Room (1946), one can’t help but be intrigued by the setup – abstraction morphing into an imagined reality or vice versa. Her title has provided the onlooker with a closed space and the suggested relationship between her geometric shapes. Is one figure with what appear to be feet turning away while another stands awkwardly frozen in space? The artist tempts the viewer to guess.

Puerto (1947), another woodcut by this artist, makes the task of finding a doorknob in the squares, rectangles and circles irrelevant. The work is a beautifully realized composition of muted sea greens and crimsons and black strokes that may or may not delineate her subject.

In Mina Citron’s Death of a Mirror (1946), one finds a mastery of black, gray. and white shapes fighting for dominance with patches of squiggling lines suggesting shattered glass.

Some titles invariably challenge us to find the defining subject. Conversely, others challenge us if not to find credence in the words, to reject them altogether. Certainly, the Surrealists, even if figurative in approach, flung nonsensical titles every which way, defying a rational response.

A vital gathering place for printmaking was Atelier 17, the avant-garde studio that flourished in New York City between 1940 and 1955. It facilitated women artists’ exposure to modernist styles and a sisterhood of networking decades before the women’s art movement of the 1970s.

Two artists in the exhibit who benefited from their association with the Atelier were Norma Morgan, one of two Black women to show there, and Teresa D’Amico Fourporne. Morgan’s Turning Forms (1950) employed color engraving and aquatint. Fourporne emigrated in 1941 from Brazil to study at the Art Students League. After joining Atelier 17, she created Braco e Negro (1945), a work made by using intaglio, a process in which lines and shapes are incised into metal plates

Irene Rice Pereira was a Spanish emigrant whose works, such as Abstract Composition (1938), were based on pure form and not derived from the real world—in an effort to “create new forms to express the new age.” Inspired by theories of perception, psychology and physics, she interwove rectilinear shapes, suggesting a continuous movement within the picture plane. In 1953, Pereira became the first woman to have a retrospective at the Whitney Museum.

West Coast artists were hardly unaware of these new and revolutionary inventions in printmaking. Ray Kaiser from Sacramento is presented by an offset lithograph, Untitled (1937), which combines distorted figures in a boldly erotic work. Dorr Bothwell, a San Francisco native, was an early feminist and a world traveler. Her screenprint, Corsica (1950), invites the viewer to make visceral associations with the country in question. The red is a vibrant yet muted choice, bordered by muted greens and blues with a school of fish that streak across the upper part of the canvas. A cross hatching of black lines seem to say “stay away” in this watery world of total abstraction.

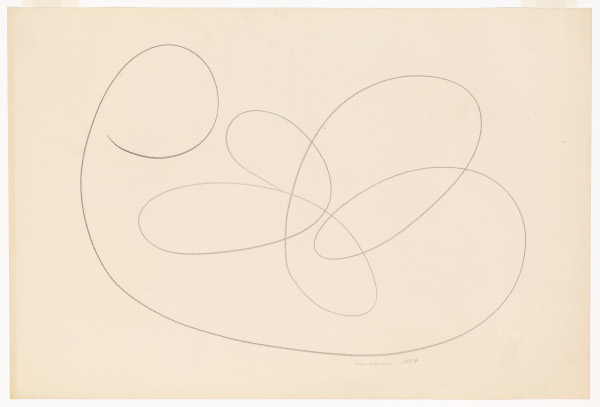

The most prominent artist in the bunch is Louise Nevelson, a legendary sculptress born in Ukraine, but an American icon of originality. Here she is represented by a graphite sketch, Untitled (1935), that looks as if it was done offhandedly, an afterthought of automatic drawing. In one seemingly continuous loop, she suggests the form of a reclining woman.

Even in this small exhibit for the Whitney, there are standout works of excellence. Most importantly, it shows that these early- to midcentury artists were determined to form a beautiful friendship with abstraction and make their mark on history.

Labyrinth of Forms: Women and Abstraction, 1930-1950, runs through March 13, 2022.

Author Bio:

Sandra Bertrand is Highbrow Magazine’s chief art critic.

For Highbrow Magazine

Image Sources:

--The Whitney Museum:

(1) Lee Krasner, Still Life (1938)

(2) Alice Trumbull Mason, Labyrinth of Closed Forms (1945)

(3) Charmion von Wiegand, Untitled (1942)

(4) Sue Fuller, Lancelot and Guinevere (1944)

(5) Louise Nevelson, Untitled (1934)