Marta Minujin Is a Tsunami of the Art World

Marta Minujín in Paris, with her first multicolored mattresses, 1963. Marta Minujín Archive. © Marta Minujín, courtesy of Henrique Faria, New York and Herlitzka & Co., Buenos Aires.

Some artists make a splash from their first entrance. With enough talent, timing, and tenaciousness it’s almost a given. In the case of Argentinian-born Marta Minujin, she possesses all those attributes and more. Over a six-decade career that embraced soft post-war soft sculptures, large-scale fluorescent paintings, psychedelic drawings, and pioneering pop art performances, she has collided head-on with her critics. She was and remains, without exaggeration, a human tsunami of the art world.

Thanks to impeccable timing and foresight, the Jewish Museum has mounted the first major survey exhibition of this Latin American artist. Marta Minujin: Arte! Arte! Arte! includes nearly 100 works drawn from the artist’s archives in Buenos Aires as well as private and institutional collections. With eye-popping precision, the exhibit charts not only her early experiments and ephemeral happenings in her home country but time spent in Paris, New York, and Washington, D.C. It’s a whirling kaleidoscope of delight.

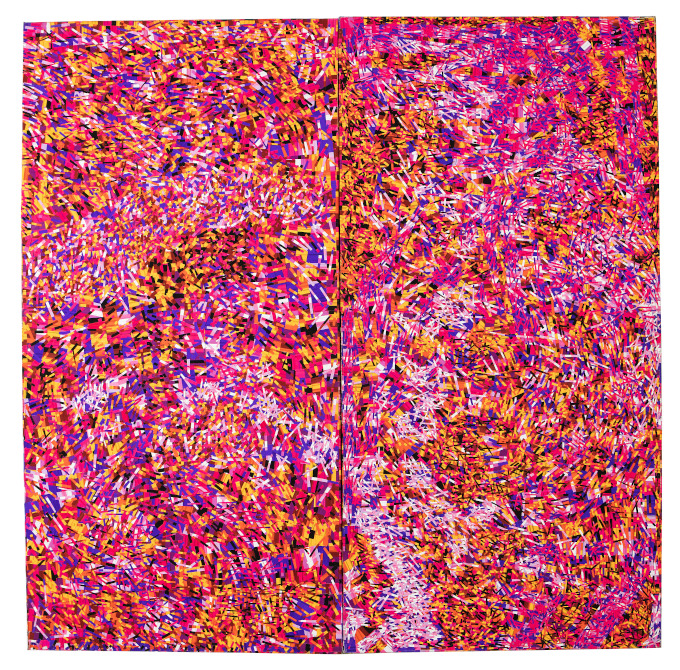

Marta Minujín, AMANACER EN PATAGONIA (SUNRISE IN PATAGONIA). 2012. Acrylic and tempera on hand-cut mattress fabric strips glued with vinyl adhesive on canvas. 94½ × 94½ in. (240 × 240 cm). Collection of the artist. © Marta Minujín, courtesy of Henrique Faria, New York and Herlitzka & Co., Buenos Aires.

Born in 1943, her indomitable spirit and irreverent in-your-face response to authority was shaped early on as her native Argentina seesawed between democracy and dictatorship. By the time she was 25—despite a brutal military junta that held sway until 1983—she was caught up in an explosion of arts in the culture. Her cry of “Arte! Arte! Arte!” resounded across continents.

One of the earliest works on display is a vibrant abstract painting inspired by Vivaldi’s Four Seasons (1959). One of three such works based on classical music, Minujin soon moved away from painting’s formalism, only to return later with the vibrancy of color as a signature element.

Marta Minujín, Colchón (Mattress), 1964, restored in 1985, acrylic, tempera, and lacquer on mattress fabric with foam rubber, 59 × 34¼ × 21¼ in. (150 × 87 × 54 cm). Collection of Jorge and Marion Helft, Buenos Aires. © Marta Minujín, courtesy of Henrique Faria, New York and Herlitzka & Co., Buenos Aires.

An early ‘60s example of the use of color is evidenced in her mattresses. Fluorescent stripes cover foam-rubber biomorphic shapes. Her core interest in mattresses is explicit in this quote from the exhibit: “Half of your life takes place on a mattress. You are born, you die, you make love, you can get killed on the mattress. That’s why mattresses are so important.” The medium has remained an obsession with such works as Soft Maze from 2010, the fabric splayed with neon bars.

Her Paris years became the site of inflammatory performances where the ephemerality of her creations was the whole idea. With The Destruction, fellow artists like Niki de Saint Phalle and others were invited to cut and manipulate her shapes that were then set on fire so they would not end up in “cultural cemeteries.” A digital slideshow reproduces one of these events. The counter-culture movement in the mid-60s in New York inspired her to return to Buenos Aires, introducing the music of Jim Hendrix and Janis Joplin, along with psychedelic projections and black lights, to the uninitiated.

Marta Minujín inside Implosion!, Pinacoteca de São Paulo, 2023. Photograph by Beto Assem. Courtesy Marta Minujín Archive.

Another series of photos pairs the artist with Andy Warhol in a playful vignette, wherein the two sit surrounded by ears of corn, “the Latin American Gold” to symbolize the means whereby Argentina could repay its loans to the U.S. Another later performance piece, performed in New York City in 1977, uses boxes of grapefruits strewn about the space by bucket-headed actors. Under a heading of “Agricultural Art in Action,” it raises the age-old question, “But Is It Art?” It is fairly certain that such issues were of little or no concern to the artist then or now.

Rejection was second nature to Minujin. While living in Washington in the early ‘70s, her paintings resurfaced in a Frozen Sex series using a pink, red, and violet palette. Though her giant semi-abstract shapes seem harmless by today’s standards, in Argentina, the same exhibit was shut down by the police three hours after its opening.

Marta Minujín, Sin título (Untitled), 1974, from the series Frozen Sex, 1973–75, acrylic on canvas, 50 × 50 in. (127 x 127 cm). Collection of Ama Amoedo. © Marta Minujín, courtesy of Henrique Faria, New York and Herlitzka & Co., Buenos Aires.

If rejection was one thing, risk taking with expansive public installations was another one entirely. After the fall of Argentina’s dictatorship, she installed The Parthenon of Books in the heart of Buenos Aires, comprising more than 20,000 publications banned by the military, and redistributed to the public at the exhibit’s close. In 2017, on the original site of a Nazi book burning in Kassel, Germany, she restaged the work. On the back wall of this exhibit, rows of banned books are on display as a reminder of such consequences to the culture.

In a more philosophical turn, toppling public monuments on their side was another way to diminish the power of the vertical in architecture. Bronze reproductions of the Statue of Liberty, a fragmented Venus de Milo and even Big Ben came under her scrutiny. In 2021 a half-size horizontal replica made of books called Big Ben Lying Down was exhibited in Piccadilly Gardens, Manchester. Once again, visitors were allowed to destroy the sculpture by taking away the books.

Marta Minujín, La Torre de Babel con libros de todo el mundo (The Tower of Babel with Books from All over the World), Buenos Aires, 2011. Photograph. Marta Minujín Archive. © Marta Minujín, courtesy of Henrique Faria, New York and Herlitzka & Co., Buenos Aires.

A separate lighthearted installation pulls the viewer inside an enclosure tent, where psychedelic colors assault the senses on walls, floor, and ceiling. This total immersion is a dizzying experience for the older set but during my visit, a young boy, accompanied by his mother, seemed totally at home in this Alice in Wonderland world.

A video from the artist’s performances in her studio demonstrate the same irreverence and sense of fun. During the Covid quarantine, she donned various masks, human and animal, as well as one of her familiar jumpsuits, cavorting in front of the camera for her Instagram fans.

Marta Minujín and Andy Warhol, El pago de la deuda externa argentina con maíz, “el oro latinoamericano” (Paying Off the Argentine Foreign Debt with Corn, “the Latin American Gold”), the Factory, New York, 1985 / 2011, Chromogenic color print, 36 3/8 × 39 1/4 in. (92.4 x 99.7 cm). Collection of the artist. © Marta Minujín, courtesy of Henrique Faria, New York and Herlitzka & Co., Buenos Aires.

Fearlessness remains a byword for artists like Minujin. She and other contemporaries like Judy Chicago and the Serbian performance artist Marina Abramovic make no apologies for where their artistic journeys may take them. Minujin’s maxim that “Everything is art” has sustained her well. Whether her audience embraces such an egalitarian philosophy or not is hardly the point. She wakes us up from a comfortable sleep, like that insistent rooster in the farmyard, and isn’t that what it’s all about?

Marta Minujín, Untitled drawing from the X×Y series, 2019-23, marker and pencil, 16 9/10 x 22 2/5 in. (43 x 57 cm). Collection of the artist. © Marta Minujín, courtesy of Henrique Faria, New York and Herlitzka & Co., Buenos Aires.

Marta Minujin: Arte! Arte! Arte! is on view at the Jewish Museum through the end of March 2024. (All images are courtesy of the museum.)

Author Bio:

Sandra Bertrand is Highbrow Magazine’s chief art critic.

For Highbrow Magazine