The Best Films of Martin Scorsese

December 26, 2013. I am 15 years old living in the suburbs of Sacramento. That afternoon my mom dropped my friends and me off at my local movie theater, thinking we were going to see The Secret Life of Walter Mitty. Little did she know, one of my friends had a brother who worked at the movie theater, who agreed to sneak us into a 5:30 pm screening of the newest Leonardo DiCaprio film, The Wolf of Wall Street. For the next three hours, as I sat in that theater and watched debauchery consume every scene, I found myself in awe of the style of filmmaking. It was so aggressively fast-paced. It felt dangerous, yet so alluring. I remember after the movie Googling information about the film, only to find a picture of the director, which caught me off guard. I had wrongfully assumed that this Martin Scorsese fellow must be a young and hungry director. Instead, I was greeted by an older, shorter gentleman with a big goofy smile. How could this guy have directed that movie?

That was my first encounter with Martin Scorsese, a director who shaped my teenage and early adult years. Possibly the greatest American filmmaker, Scorsese is incapable of making uninteresting films, thus defining his 10 best films would be a fool’s task. In curating these titles, it's less a question of greatness, but rather selecting the titles that I believe surmise Scorsese, the artist and person. These titles spanning over his seven-decade career vary in genre, tone, production value, and style, but they share one connection: They offer insight into the human experience and represent a moment in time in our understanding of culture.

After Hours (1985)

Poor Paul Hackett -- a man who risked it all in the hope of bedding Rosanna Arquette. After Hours can be likened to Homer’s Odyssey, where our protagonist, an officer worker by the name of Paul finds himself entangled in a series of misadventures while attempting to escape New York City’s SoHo district after a one-night stand goes awry. Like Homer’s work, After Hours sees our hero on a mission to return home, yet divine intervention thwarts Paul’s every move. Scorsese's mean-spirited approach to comedy allows Paul to become a figurative punching bag for the creative team as they explore new ways to torment their protagonist.

Killers of the Flower Moon (2023)

Walking out of Scorsese’s latest film, I found myself conflicted about Scorsese’s ability to tell this Osage-specific story. Yet, that discomfort is deeply rooted in the narrative structure of this story, as well as a reflection of the director’s reconciliation with his film. Growing up a student of John Ford’s films, Killers of the Flower Moon owes much of its visual language to the iconography of Ford and John Wayne, while also serving as a reconciliation of their lasting influence. Killers of the Flower Moon tells the horrors of complicity, as a nation watches the genocide of the Osage people. While the killers are obvious, the community is vulnerable, much like lambs to the slaughter, aware that no one is coming to their rescue. Scorsese wisely chooses to adapt David Graham’s novel and shifts the focus not on the genocide itself but on the perpetrators.

Hugo (2011)

When studying Martin Scorsese, the artist, and the person, we talk about the brilliance of his directing techniques, the moral conflicts of his protagonists, and his Catholic upbringing, but we often forget the missing ingredient. Scorsese is first and foremost a lover of cinema. Hugo is a case example of how devout his love of film is. The story follows a young boy who searches for answers to questions left for him in his late father’s notebook, which ultimately leads him to cross paths with famed director Georges Méliès. Like Scorsese, Hugo Cabret finds healing in movies, and joy in discovery. The protagonist and Scorsese are directly parallel -- as Hugo uncovers the wonder of early special effects, Scorsese marvels at the innovation of modern special effects, and in doing so creates a narrative that is wholly joyous within the director’s lexicon.

The Departed (2006)

“No one gives it to you; you have to take it,” Ironically, Jack Nicholson’s Frank Costello opens the film by articulating the hubris that leads to every character's downfall within The Departed: the misguided belief that one is the sole author of their life story. In reality, crime operates as a cancer that promises to destroy everything it comes in contact with. No character is altruistic and their allegiances mean nothing within the context of death. It is no coincidence that The Departed chooses to tell its story in Boston, a city where in 2006, even the priests were involved in organized crime and coverup. Sin belongs to the eye of the beholder, forcing our characters to all reconcile with what they deem right. In this world, honor and respect are only granted to the departed, and everyone else is left fighting for scraps.

The Wolf of Wall Street (2013)

Of all sins, stupidity is the most dangerous. Stupid people have the power to destroy lives. And no Scorsese protagonist is stupider than Jordan Belfort, the self-appointed Wolf of Wall Street. The antics of Belfort and his cronies at Stratton Oakmont display behavior that is as exploitative as it is juvenile, yet the bombastic soundtrack, fast-paced editing, and cocaine-fueled hijinks serve to discombobulate audiences. Scorsese’s style is so aggressive that it works to exhaust audiences, to the point that they too get sucked into this world of debauchery… that is until it all comes crashing down and we are forced to remember the real-life implication of Belfort’s crimes.

Goodfellas (1990)

Arguably the most influential of Scorsese’s movies, Goodfellas is the moment Martin Scorsese redefined crime stories. Fittingly, released the same year as The Godfather: Part III, Goodfellas served as the natural progression within the genre that Coppola had helped to contextualize himself in the 1970s. Here, we follow Henry Hill, a man who from a young age saw the glory of organized crime. Ray Liotta stars as Hill, a man who lacks conviction. Hill is a yes man, arrogantly believing that the little amount of wealth he has earned for himself will last. When his kingdom begins to crumble, Hill’s hubris leaves him trapped in a game of cat and mouse where he learns he is no longer the apex predator.

Silence (2016)

A quality that is underrated within Scorsese’s filmography is his ability to locate young promising stars and utilize their inexperience to better serve his story. In Silence, Andrew Garfield appears too young to play the role of Father Rodrigues, a Jesuit priest forced to examine the paradoxes of his faith. The film is metatextual in its story of a man and its lead actor trying to prove themselves. Both Rodrigues and Garfield desperately seek to prove themselves worthy of the responsibility. Where Rodrigues seeks assurance in his faith, Garfield seeks Scorsese’s approval of his talents despite Adam Driver and Liam Neeson outperforming him in every scene. In doing so, Garfield’s performance mirrors Scorsese’s religious journey of a man reconciling with his faith only to find peace as his life nears an end.

Taxi Driver (1976)

What I have always found so interesting about Taxi Driver is the moment in which it captures New York City. Coming out of Vietnam and the Watergate Scandal, New York becomes a hodgepodge of politics and culture. It is a city where Scorsese, Woody Allen, and Saturday Night Live can all cohabit at the same time and feel wildly distinct in tone. Taxi Driver represents the fault lines of the tumultuous 1960s, where political leaders were killed left and right, a war divided our country, and man realized that our existence was meaningless when compared to the cosmos of space. In the aftershock, some like Travis Bickle are left behind, now trapped in a world unrecognizable, forcing him to resort to violence to reestablish control.

The King of Comedy (1983)

Of all of Scorsese’s stories, I found The King of Comedy to be his most upsetting. While it lacks the ferocity of Raging Bull, and the violent imagery of Taxi Driver, The King of Comedy captures a psychosis that closely resembles America in the age of social media. Scorsese’s direction is infused with brimstone anger, as he holds a deep disdain for his protagonist, Ruper Pupkin, a narcissist, who deludes himself into believing himself the second coming of comedy. The extent to which he is willing to go is truly chilling. As time passes, the satirical elements in the film fade, and what remains is a reflection of a society where Rupert Pupkin-like individuals are now empowered and given wider access to platforms to gain notoriety at any length.

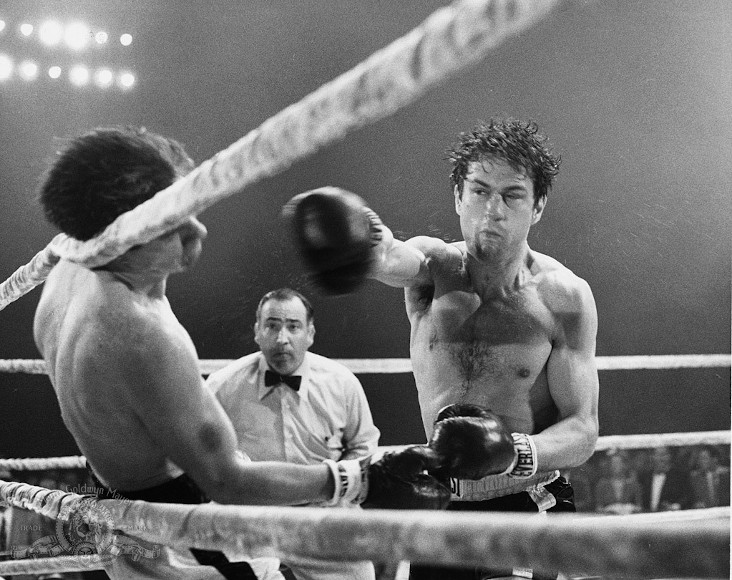

Raging Bull (1980)

Recently left almost for dead by a nasty cocaine addiction, Scorsese finds himself fighting for his survival, resulting in his masterpiece Raging Bull. The film follows Jake LaMotta, a man with all the talent in the world who simply cannot get out of his way. For LaMotta, life is a constant battle of me versus them. It tells the story of self-destruction as a man succumbs to this mindset, and sees the world akin to a boxing ring. For LaMotta, life becomes survival of the fittest, forcing his isolation and alienation of anybody who ever once loved the raging bull.

Author Bio:

Ben Friedman is a contributing writer and film critic at Highbrow Magazine.

For Highbrow Magazine