Winslow Homer at the Met: A Study in Conflict

What makes a man great? Shakespeare in Twelfth Night didn’t think it was such a mystery: “Some are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon them.” For Winslow Homer, every part of that definition seems apt.

Visitors to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s current exhibition can decide for themselves whether or not this renowned 19th- and early-20th-century American painter fits the Bard’s lofty description. And they will have ample opportunity, with an impressive collection of 88 oils and watercolors, the largest critical overview of Homer’s art and life in more than a quarter of a century.

Born in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1836, Homer came from a long line of stalwart New Englanders. His mother was Homer's first teacher and a gifted amateur watercolorist. Homer absorbed many of her traits, including her strong-willed, terse nature; her dry sense of humor; and most importantly, her artistic talent. At 19, he was apprenticed to a commercial lithographer, followed by a long stint as a freelance journalist for Harper’s Weekly. This carried him into the thick of the American Civil War (1861-1865) and though knowledge of his experience on the battlefield is sketchy at best, his mother was to remark that upon coming home, “he was so changed that even his friends didn’t recognize him.”

The clean, white partition walls of the exhibition--with cutouts between rooms that draw the visitor backwards and forwards for further viewing—provide a visual interplay between the artist’s evolutionary periods. Upon first entering, Homer’s early landscapes of the Reconstruction period hardly prepare one for the turbulent conflicts between man and nature to come. Redolent of French painter Jean-Francois Millet’s somber evocations of peasant farm workers, they evoke the artist’s ability to convey in exquisite detail the daily life he knew.

A welcome respite from his muted color palette of dark umbers and browns is the crowd pleaser Eagle Head, Manchester, Massachusetts (High Tide) from 1870. The sight of three young women at surfside, a small nearby dog startled as one girl wrings out her sopping wet skirt, is a joyful moment.

Exposed to works of the early Impressionists following a year’s stay in Paris, Homer’s own style stayed solid. His most praised early painting, Prisoners from the Front, gained recognition in Paris during this sojourn. A Union officer confronts a band of Confederate soldiers but each side stands firm. The tension is palpable. In another, the former white mistress of three Black freed women with child faces her former slaves. This is a murky encounter, another example of the artist’s coming to terms with a new post-war world.

Dressing for Carnival,(1877) features a Black man being sewn into his Harlequin costume by family members for a traditional African celebration. Is this a promise of better times for these former slaves, which the wall notes suggest? Perhaps. A helpful hint to visitors would be to let the magnitude of the art speak for itself first, then use the history lesson as needed.

A good example is The Cotton Pickers (1876). A pair of hardy muscle-bound women fills the canvas. Their dark forms cut into the foreground, contrasted by the clusters of snowy cotton in their shoulder bags. The image needs no explanation.

Such physical prowess in Homer’s female figures is on display in The Gale, his culminating image of Cullercoats fisherwomen. These subjects were inspired by a two-year stay (1981-82) along the English coast of Northumberland. He reworked the painting over the course of a decade to counter the more frequent images of men in their struggles against the elements. Undertow (1986), a composition of unbelievable power in its depiction of the rescue of two women from drowning, stands as one of Homer’s very best. By this time, he had mastered not only the human figure in whatever calm or distress he chose, but had proven to be a master interpreter of water, sky and earth —in short—the whole of the natural world.

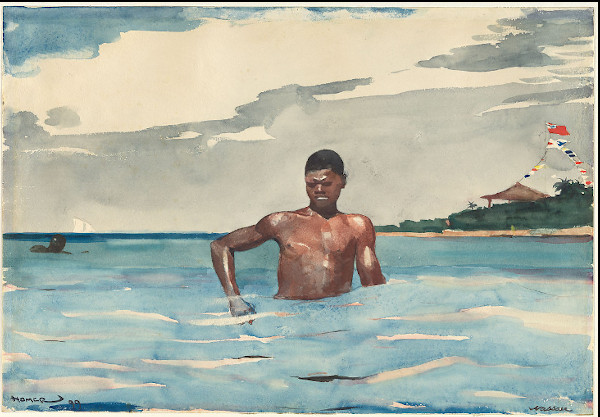

Curators Stephanie Herdrich and Sylvia Yount have used conflict as the major theme of this exhibition. To that end, they have chosen The Gulf Stream (1899) as the centerpiece of Homer’s art. (The Gulf Stream is named after the strong Atlantic current that connected many of the locales where he liked to paint.)

The painting remains a testament to his strengths as a storyteller. Will his Black sailor survive in a mastless boat, alone and surrounded by hungry sharks? Painted shortly after his father’s death, The Gulf Stream has been interpreted as an expression of human vulnerability and mortality. One of many studies for this work demonstrates his fluidity with watercolor. A few strokes reveal a perfect blur of sharks circling an empty boat.

Happier examples of his genius at watercolor abound. Palm trees, fishing boats, delectable oranges and a charming criolla, a Cuban woman of Spanish descent with fan, are all here for the viewer’s delight.

Two paintings that stand as portents to the vulnerability of all creatures in the natural and unnatural world, and arguably his finest, are Fox Hunt from 1893 and Right and Left (1909). In the first, a beautifully rendered fox is caught in snow drifts while crows loom overhead. The latter, painted a year before his death, shows a pair of goldeneye ducks in a frenzied air dance. Only a close inspection reveals a tiny burst of red from a hunter’s rifle in the lower left of the canvas. Apparently, his genius for surprise did not diminish with age.

There are lessons to be learned here—the mutability of life in war and peace, the ongoing struggle of man and woman against the forces of nature, the indisputable power of nature itself. To succeed in their depiction is remarkable. Just don’t look for an ending tied up with a bright bow for easy consumption. These are great themes from a great artist.

--All images courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Author Bio:

Sandra Bertrand is Highbrow Magazine’s chief art critic.

For Highbrow Magazine