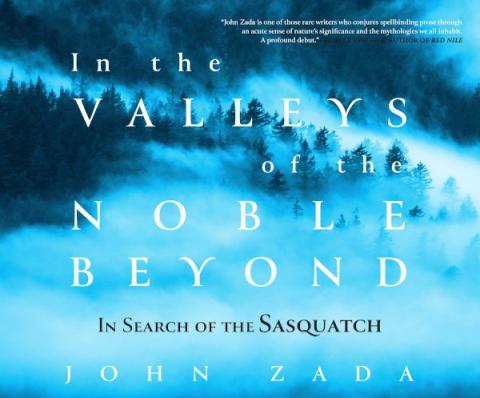

Desperately Seeking Sasquatch in John Zada’s ‘Valleys of the Noble Beyond’

In the Valleys of the Noble Beyond: In Search of the Sasquatch

By John Zada

Atlantic Monthly Press

306 pages

Does Sasquatch exist? This question propels journalist and photographer John Zada on multiple journeys to the Great Bear Rainforest in British Columbia for his new book, In the Valleys of the Noble Beyond.

In small towns and villages, Zada meets many people who claim to have seen the Sasquatch, “the alleged race of half-man, half-ape giants” on the loose in the wild. Like its distant counterpart, the Yeti, a rumored denizen of the Himalayans, the Sasquatch, aka Bigfoot, has purportedly left behind footprints and engaged in random encounters with hunters, fishermen, and members of the Kitasoo, Heiltsuk, and other First Nation peoples.

What does the creature look like?

“Covered in either black, brown, red, gray, or white hair, the adult Sasquatch stands anywhere from around six and a half to ten feet tall … Some Sasquatches give off a wretched, indefinable smell, likened to that of a wet dog that has rolled in its own excrement and rooted in garbage … Loud vocalizations, throwing rocks and branches, stomping, whacking tree trunks with sticks, and slapping and shaking buildings are frequently reported behaviors.”

It’s understandable why those who say they’ve crossed paths with Bigfoot never forget the experience.

And make no mistake, those who believe in the existence of Sasquatch really believe. One such “Sasqualogist” is John Bindernagel, a dedicated wildlife biologist, “who, for most of his life, has known the relentless pursuit of a creature that the wider world, including his own colleagues, insists does not exist.”

In this pursuit, he wanders out from his residence on Vancouver’s east coast to set battery-operated digital trail cameras (“camera traps”) with the goal of capturing the elusive beast in its native habitat. Thus far, the camera traps have gathered “loads of great images” of deer, black bears, and cougars—but no Sasquatch. Yet, as Bindernagel contends, numerous firsthand reports and findings of enormous tracks serve as evidence of the elusive beast’s existence. His commitment to what others view as a quixotic journey has resulted in the publication of several Sasquatch-themed books, years in the making, that have “landed with a thud” in the scientific community.

Bindernagel’s tragicomic quest is one of many heart-tugging stories Zada describes, among those who contend the Sasquatch remains at large in a region of rainforest that adds up “to some thirty thousand miles of shoreline—a length greater than the circumference of the earth.”

To his credit, Zada—a self-described skeptic, at least at the book’s outset—does an impressive journey of sowing doubt in the minds of equally skeptic readers. After all, for every account and piece of grainy, black-and-white footage, no credible scientific evidence has ever emerged that definitively proves that Bigfoot exists.

How is that possible in a digital era where virtually all of the earth’s land mass has been viewed or at least glimpsed at by drone or orbiting satellite? Consider this, Zada writes:

“Bigfoots may be unbelievable to so many people simply because most of us are disconnected from the true depths and expanses of the earth and its wild areas. We simply may not be able to conceive of Sasquatch habitat … Few, if any seasoned travelers or explorers think the planet has been comprehensively probed. I find it is mostly those living in and around big cities, with little or no experience with or appreciation for remote, unpopulated areas, who most often declare, ‘But the world has been explored!’ Their limited urban or suburban existence has deeply conditioned them to this view.”

By contrast, many of the people Zada meets in and around the Great Bear Rainforest have a far deeper understanding of the region’s vastness and impenetrability. To them, it’s obvious that “being a rare and mostly nocturnal animal would only make it that much more difficult to find.”

If at times, In the Valleys of the Noble Beyond feels overwritten (“the symphonic pitter-patter of reconstituted sea” and “plastic surgeons of sprawl”), Zada comes across as an earnest, credulous investigator of the mythical creatures said to be roaming this isolated expanse of North America.

As far as the author is concerned, “some questions have no answers” and it’s entirely possible that, with respect to the Sasquatch, “we may simply never know.”

A well-earned conclusion to a tale that, for many, is yet to be resolved.

Author Bio:

Lee Polevoi, chief book critic for Highbrow Magazine, recently completed a novel, The Confessions of Gabriel Ash.

For Highbrow Magazine

Image Sources:

--Steve Baxter (Pexels, Creative Commons)