Women Artists and Postwar Abstraction at MOMA

The first thing I noticed upon entering this exhibit was the intentional spacing of the show title that greeted me: The words “Making” and “Space” were placed at the beginning and end, while “Women and Postwar Abstraction” had been squeezed in between. All but one of the 94 works by 53 international women artists on display, drawn from MOMA’s own collection, have finally taken center stage.

That’s a subtle but important way of the curators saying that it is high time these talented and transformative artists find their rightful place in the brash, male-dominated universe of abstract expressionism. For too long the likes of Helen Frankenthaler, Joan Mitchell, Grace Hartigan, Louise Bourgeois and others worthy of visibility have been brushed to the sidelines of modern art. As Peter Schjeldahl said in his April 24th New Yorker review, the post-war world left women “less with glass ceilings than with absent floors.”

It's an old story, one that should have been relegated to the dustbins of history long ago, but the environment in which artists like Berthe Morisot, Georgia O’Keeffe, Frida Kahlo and Lee Krasner to name but a few grew up was rigidly defined. Women were hardly solitary stars but marked by the liaisons, constellations if you will—familial, marital and otherwise—that allowed for their creative endeavors to flourish.

In Morisot’s case, it was her brother-in-law Edouard Manet; in O’Keeffe’s it was her husband and mentor Alfred Stieglitz. In Frida’s world, it was her own unique surrealistic genius and magnetic personality that held sway over the gigantic personage of her muralist husband, Diego Rivera. And in Krasner’s case, Jackson Pollock hovered nearby—a revolutionary presence that we can assume didn’t suck all of the oxygen out of their studio space.

Thanks to curators Starr Figura and Sarah Hermanson Meister, with help from Hillary Reder, there’s an airy, capacious feel to the entire exhibit, giving these creations—from Ann Ryan’s miniature but magnificent collages to the monumental woven sisal sculpture by Polish artist Magdalena Abakanowicz, room to breathe. In the latter’s case, this massive sienna-colored piece is positively monolithic, imperiously looking down at the viewer as something alternately timeless and terrifying in its beauty.

For many of these artists, a nod to more intimate, personalized approaches was subsumed into a more universal abstraction. Grace Hartigan’s Shinnecock Canal, situated on the south fork of Long Island, has an almost magnetic appeal through its great blocks of color and zigzag motion. Such a bold treatment of theme was attributed to a certain “George” Hartigan (a nom de plume briefly used by the artist).

The Romanian-born Hedda Stern fled from Bucharest during the Nazi occupation, finding inspiration in New York’s interwoven highways. Her Road series of paintings shuns color for charcoal streaks and shadows, the blur of erratic white spots giving the impression on second viewing of converging headlights. Another example of the undeniable power of dark tones is reflected in Helen Frankenthaler’s Trojan Gates (1955) where her huge columns suggesting ominous barriers hold sway. In contrast Joan Mitchell’s turquoise and magenta shapes, arbitrarily dripping down the canvas surface, put her squarely in a natural universe of color (though don’t expect to locate the Ladybug of the painting’s title!). Elaine de Kooning’s Bullfight (1960) saturates the picture panel with color, introducing a dead-center frenzy of black.

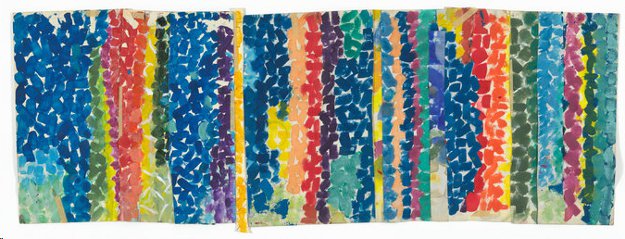

A lighter approach is evident in Alma Woodsey Thomas’ patterned squares. A school teacher who didn’t begin painting until her retirement, she became in 1972 the first African-American woman to receive a solo show at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Close by, Lee Krasner’s gigantic canvas of pink and white amorphous egg-like shapes is encountered. Her Gaea, after the Earth Goddess, manages to bring an element of femininity into this whimsical mix without compromising its essential force.

Photography is obviously a medium well suited to experimentation and generously represented by several works of note. The most riveting to be found are the works of Gertrude Altschul, a German-born Brazilian. Nurtured by her association with Foto Cine Clube Bandeirante, a groundbreaking group of photographers in Sao Paulo, her works make clear her mastery of technique. Reflected shadows from a ubiquitous ladder exemplify the power of geometric abstraction. My favorite image features a roll of paper, seemingly lit from within, with a rogue cigar smoldering nearby. An uneasy tension is thereby created by this simple juxtaposition.

The inherent playfulness to be found in many of Picasso’s sculptures is here evidenced in Dorothy Dehner’s six bronze totems. They seem in their arrangement to confront one another’s alien personages. Louise Nevelson’s Big Black from 1963 presents the viewer with a series of conjoined wooden black boxes filled with an arbitrary assortment of dowels, spindles, and stray furniture parts. Austere and unapologetic, Nevelson gives us in her words “a black that encompasses all colors.”

The elegant use of fabric is nowhere better represented than in Annie Albers’ free-hanging room divider. She and husband Josef Albers were instrumental in their early work with the Bauhaus School of Design, where she was director of weaving until the Nazis closed the school in 1933. The pair subsequently emigrated to the United States, teaching at the famed Black Mountain School in North Carolina.

The appropriation of natural materials beyond the practical to convey emotive power was adopted by several artists found here. Abakanowicz’s earlier mentioned fiber work takes prominence but that artist keeps stellar company with Louise Bourgeois’ The Quartered One (1964), a Bronze lair or trap but also reminiscent of a carcass, hung as it is from a giant meat hook. For some it’s an ugly business to behold, but it clearly falls in that realm where art can be—take it or leave it—what the viewer makes of it.

This work, like the intentions of a percentage of artists on display, takes no prisoners. Lee Bontecou’s untitled wall sculpture—a concoction of steel, canvas, and discarded conveyor belts from the artist’s own neighborhood laundry—could be a set piece for a production of Sophocles’ Medea, pulling the viewer into its cavernous vortex.

This is an exhibition not to be taken lightly—celebrating the ambitious scope of these artists’ intentions as much as the works themselves. MOMA at last has chosen to make space for these formidable women, but there’s little doubt that these creators have chosen—come hell or high water—to take it for themselves.

(Making Space: Women Artists and Postwar Abstraction will run through August 13, 2017.)

Author Bio:

Sandra Bertrand is Highbrow Magazine’s chief arts critic.

For Highbrow Magazine