Love, Deceit, and Catfishing: The Perils of Social Media

In 2010, a major feature film was released revolving around social media: the award-winning The Social Network. Penned by Aaron Sorkin and directed by David Fincher, the film was released on September 27th to critical and commercial acclaim. It tracked the origins of Facebook, the social media giant, as it explored the lives of its creators.

In an early scene, Mark Zuckerberg (played by Jesse Eisenberg) creates a campus website called Facemash – a sort of “hot or not” game where pictures of female students, taken from hacked college databases commonly known as “facebooks,” were posted side by side and visitors were asked to rate their attractiveness. An early precursor, the fact that this initial site used people’s images matched with their real identities represents a key aspect of what would eventually become Facebook. A week before The Social Network was released, an indie documentary called Catfish debuted in theaters in a limited release.

Catfish follows Yaniv “Nev” Schulman, a young New York photographer. Nev begins a fraternal relationship on Facebook with a Michigan-based 8-year-old artist named Abby when she sends Nev a painting rendering of one of his own photographs. Nev and Abby become Facebook friends and this network begins to broaden to include members of Abby’s family, such her mom Angela and her 19-year-old sister Megan. Nev and Megan eventually develop a romantic relationship notwithstanding never having actually met before. They speak on the phone constantly, send each other erotic messages, and talk about the future.

When evidence emerges that Angela and Abby have been lying about the latter’s painting career and not all is at it seems, Nev begins to doubt the authenticity of his relationship with Megan. Nevertheless, at his brother’s insistence, Nev continues the relationship for the sake of the documentary until the siblings decide to travel to Michigan and meet Megan in person. It is finally revealed that Megan is in fact her mother Angela, who had been posing as her daughter while maintaining the relationship with Nev. The real Megan had been none the wiser and the paintings that Abby, the 8-year-old artist prodigy, had created were in fact Angela’s.

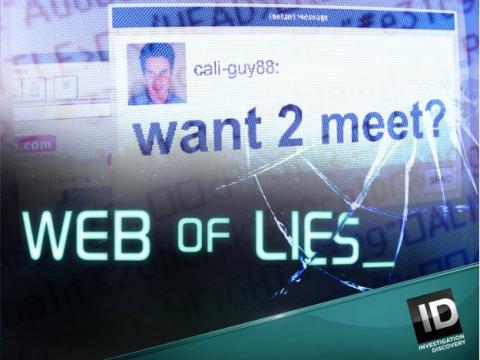

Even though the film Catfish will never actually be profitable because of two separate lawsuits, the movie became a sleeper hit of sorts, and it has quickly become a “cult classic” in the generation of networking and social media. It spawned a successful TV show currently producing its sixth season on MTV and it gave rise to the term “catfish,” which was originally defined as someone who creates an identity online on a social platform as someone other than themselves. The Merriam-Webster dictionary has officially included the term on its cannon albeit with a bleaker connotation: “A person who sets up a false personal profile on a social networking site for fraudulent or deceptive purposes.”

In the vernacular the term is also used as a verb, the deceiver being the one doing the catfishing while the victim is being catfished.

Taking up someone else’s identity, for deceptive purposes or not, is not a practice limited to the age of technology. The feat is used as a literary device in various works, such as Melville’s The Confidence-Man. It was a media frenzy revelation when JT LeRoy was discovered to be a pseudo-fictional/real character created entirely by writer Laura Albert who wrote of al LeRoy’s books, stories, articles, and correspondence while a 25-year old named Savannah Knoop alternatively played the character in “real life.” His backstory is rich with detail and facets of prostitution and drug addiction, which feature widely in LeRoy’s publications and perhaps most notably in his debut novel Sarah, which also uses identity deception as a major plot device.

But catfishing as defined by the modern vernacular is a generational singularity. An incredibly complex psychological phenomenon made possible by modern technology and the pervasiveness of social media. Exemplified perhaps not by the victimizer – after all, deception and conceit can arguably be categorized as essential human flaws – but by the targets who fall victim to other human traits: the willingness and willful desire to be deceived and believe in the least plausible likelihoods. The practice, however, can oftentimes have dire consequences.

One of the earliest and best-known cases of catfishing ending disastrously was the case of Megan Meier. 13-year-old Meier committed suicide in October of 2006 after a boy she had met online named “Josh Evans” abruptly ended their relationship. The two had never met, and it eventually came to light that Josh was a fake persona made up by Lori Drew, a neighbor who wanted to find out what Meier was saying about Drew’s daughter Sarah, who at one point had been friends with Meier.

For this purpose, Drew created a fake account on the Myspace social site and began a relationship with Meier by posing as a 16-year-old boy. Myspace was the single most popular site in the Unites States around this time, surpassing even Yahoo and Google Search in online traffic. It was one of the earliest platform networking sites available to the general public; two-year-old Facebook had opened up registration to the public only a month before Meier’s death (prior to this, it had only been available to users with active college email addresses and a number of selected corporation networks).

In what is generally considered the first case involving cyberbullying, Drew was indicted in Los Angeles after Missouri—where Meier and Drew resided—announced the state would not file charges because there wasn’t enough evidence for conviction. The U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Central District of California based the fact that Myspace was located in that state, where the site’s servers are housed, to file federal charges against Drew for violation of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. The prosecution argued that Drew that obtained and used the image of a boy and used it without his knowledge by pretending to be “Josh Evans.” In essence, Drew’s crime was that this had violated Myspace’s terms of service. The jury found Drew guilty.

Widely publicized, the case drew attention because of the lack of precedence for cyberbullying crimes and convictions. While all agreed that Drew’s actions were reprehensible, critics worried that this conviction may open up the possibility of lawsuits for minor or downright trivial offenses. Myspace ‘s terms of service prohibit a number of things, such as knowingly providing false or misleading information. This would make people who lie about their age, weight, or height on their social profiles possibly guilty of a federal crime. Citing the vagueness of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, the presiding federal judge overturned Drew’s conviction effectively vetoing her guilty verdict.

Catfishing, of course, is also an international occurrence. In the summer of 2015 three Chechen women became Internet heroes when it was found that they had been communicating online with ISIS rebels. The ISIS members were led to believe that the women were brides who wanted to join their cause but were prevented from doing so for lack of money. The ISIS fighters wired them money so they could travel and marry them, only to find afterwards that the women had no intention of doing so and were basically scamming them for money. After receiving approximately $3,000 from the ISIS fighters, the girls blocked all communication with their victims and attempted to move on to the next target before being stopped by Chechen policy. The girls faced up to six years in prison on charges of cyberfraud for catfishing ISIS.

In an attempt to combat fake profiles, social media platforms have taken steps to minimize their numbers. In 2014, for example, Facebook began removing inactive profiles from its servers, which became apparent when several celebrities saw a sudden decrease of fan likes and followers. Pop star Justin Bieber notoriously lost three-and-a-half million followers after Facebook removed these fake profiles. The problem, it seems, is that it is actually very difficult for social sites to spot a fake profile.

Four years ago, it was estimated that nearly 9 percent of Facebook’s monthly active users were duplicate or fake accounts according to the data Facebook itself filed with the SEC. That is nearly 85 million active fake profiles that are being accessed at least once a month. And while the Web has a reputation of providing rampant anonymity, social platforms do encourage a greater degree of transparency. By requiring users to create profiles, this helps establish an online presence that may, in turn, help create a broader picture of a person’s real identity. Meanwhile, real anonymity is on the decline.

In 2006 when “Josh Evan” told Megan Meier “the world would be a better place without you,” social media was in its infancy. Myspace was the most widely used network and, at the time, it did provide a platform for anyone to create a profile as anyone else. Meier may have had no reason to believe that she was being deceived, nor did she have as many options to confirm the identity of her online boyfriend as we do today. There are many communication tools that make this possible. The popular messaging app KIK, for instance, carries a feature that labels whether a picture sent was copied from the user’s cellphone gallery or taken by the phone camera in real time. This would help confirm the identity of the user someone is communicating with, since anyone who downloads the app can create a profile using any name. This is assuming, of course, that the presumed deceiver wants to communicate outside of a social network.

Scholars say that a healthy dose of skepticism is always good when dealing with online relationships. Catfishers will often find excuses not to meet in person and use traumatic experiences as justifiers, such as serious illnesses or injuries. Likewise, while usually amenable to speak on the phone, victimizers would not be prone to video chat. Repeated excuses to not video chat (especially given the easy access to cameras and webcams we have today) and meeting in person are big red flags.

Notwithstanding the many ways it can be avoided, catfishing still occurs. While it does remain a rare occurrence, it has generated an entire television show spanning at least 69 episodes by the end of its fifth season. When Nev began his relationship with Megan, Facebook had already surpassed Myspace as the most popular social platform in the United States. The iPhone 4 had just been released along with the first incarnation of FaceTime. Still, it is estimated that 1 in every 10 profiles on dating sites is fake (though usually as a scam for the purpose of fraud rather than catfishing). Social networks and dating sites, despite the security protocols they have in place, rely on their users to detect and single out the scammers and catfishers. A task easier said than done given the natural human desire for sympathy, love, and the seemingly perfect soulmate – all characteristics catfishes offer.

The term “catfish” itself comes from a story Angela’s husband, Vince, recounts on the film. He explains how when cod was shipped from Alaska to China, the fish would arrive turned to mush due to inactivity. To counter this effect, catfish was added to the cod’s tanks to keep the latter active so they arrived to their destination fresh and whole. The authenticity of this practice is murky to say the least (catfish are bottom feeders after all, not active hunters), but Vince’s allegory is rich if frighteningly expressive of human nature. He concludes: “And there are those people who are catfish in life. And they keep you on your toes. They keep you guessing, they keep you thinking, they keep you fresh. And I thank God for the catfish because we would be droll, boring, and dull if we didn't have somebody nipping at our fin.”

Author Bio:

Angelo Franco is Highbrow Magazine’s chief features writer.

For Highbrow Magazine