Pathos and Minimalism: Doris Salcedo at the Guggenheim

Constructing memorials to those lost in conflict requires simultaneously painting with both a broad and fine-toothed brush (metaphorically speaking). The artist should not ignore nuanced suffering, yet the main goal is at the service of events that affect people en masse. While Doris Salcedo’s pieces, focusing on the Colombian Civil War, do not employ the typical tropes of memorials, they are still imbued with the sensitivity required of them due to her process and personal history, having lost family members to the conflict.

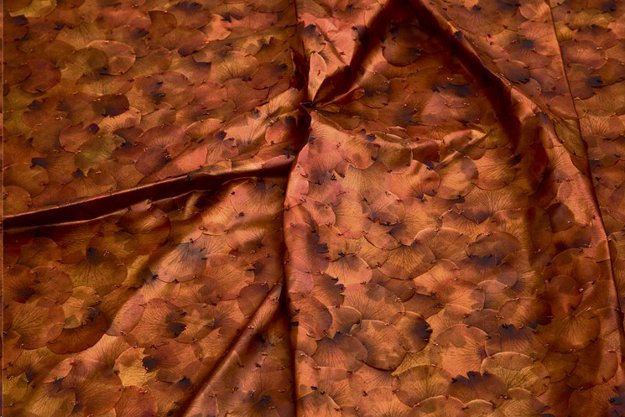

The show spans four floors and allows visitors to see a large breadth of her work. Furthermore, some of the pieces are contained in the back areas of the spiral staircase and this provides the exhibit with a kind of intimacy that people may not necessarily associate with the Guggenheim. The seventh floor’s space begins with A Flor de Piel (2014), a gorgeously eerie stitched piece that has been laid across the floor in a crinkled manner like a blanket. There are leafy patterns all along it ,and despite its simplicity it evokes tension, discomfort, and the surface is rather bodily in color and texture. Salcedo created this piece from hand-stitched rose petals as a tribute to a nurse who was tortured to death. The description reads that there is a “fairytale quality” yet the “undulating red fabric also conjures flayed skin.” It’s a good example of the duality present in her work – the fantastical and the tragic, the domestic and the political.

Her series Unland (1995-1998), also on the seventh floor, is another testament to her involvement and excessive effort in constructing her pieces. The works are pieces of furniture, which she commonly uses, that have been fused together. Upon first glance it appears that there are pen scratches on them, highlighting their look of ruin. These scratches, however, are fine pieces of human hair and thread that have “been painstakingly hand-threaded through miniscule holes.” She conceived these pieces after having interactions with Colombian children who watched their parents’ murders. The hair symbolizes a veil of pain over their lives. Knowing the excruciating exertion of Salcedo’s process deepens not only her pieces but the artist’s relationship with the victims of unnecessary pain. Through knowing and meeting them there is a more intimate connection that many memorials are void of.

Continuing on the fifth floor are more of her furniture installations that comment on domesticity disturbed by war. Visitors can walk amongst the pieces as well, which have their negative space filled with cement. This provides literal and metaphorical heaviness, and their placement is not always typical – some cabinets are on their side, chairs are facing inward towards the wall, and again she fuses separate pieces together in odd ways. Towards one end of the room is a cabinet with glass doors. At a distance, it seems that the cement filling has some sort of patterning, almost ornamentation, until you get closer. It is then revealed that there are clothes hardened into the cement. It’s grotesque in conception and heartbreaking in meaning. These items are meant to reflect the notion of “glimpses of happier former lives” that for the survivors now are “burdened by unresolved grief.”

Some of her works are more overtly violent, such as Untitled (1989-2013) that uses a copious amount of white button-down shirts ,which she then thrusts long metal rods through. It’s a highly publicized piece due to its physicality, and in person it leaves the visitor with a sense of violation. She takes a very everyday item, that most would have in their wardrobe, and cuts through it ,thereby attacking our notion of the mundane to serve as a reminder of the victims’ loss of everyday place and self.

Plegaria Munda (2008-2010) is a blatant lamentation on humanity’s capacity for brutality. Arranged in one room are rows of table couplings, with one tabletop lying flat on the other tabletop. There is dirt encased and small, fragile-looking plants have grown out of the soil. The effect upon walking into this room is at first daunting, and then as one walks through the maze of desks, quietly powerful in the subtleties of arrangement. The tables, however, are meant to resemble coffins, especially ones reserved for fallen soldiers. This piece is for “individuals killed in gang violence in the United States, as well as rural Colombians murdered by the military and presented as guerilla fighters in return for government rewards.” Salcedo has explicitly incorporated a place other than Colombia with this piece, and emphasizes the instances of killing to reap money and/or power. There is an added component, typical of Salcedo’s particular brand of romanticism, in her use of soil and plants. As she says, “The meadow that reclaims the grave is an agent of healing but also forgetting.” She’s interested in commenting on the aftermath of loss and on how with those who have survived the type of conflicts that yield massive death tolls, there is always a fluctuation between grief and healing.

While at the exhibit I overheard a visitor say, “You always have to stand back with her work first.” While this is logistically good advice ,it also speaks to the type of work Doris Salcedo creates. Her obsessive attention to the details is only realized by the viewer on closer inspection, and in doing that there is a greater awareness of the real plight that individuals afar have had to experience. It is noted, astutely, that the furniture can act “as surrogates for absent or injured bodies” and in that way her approach to minimalism is imbued with “profound pathos.” However, while it might be easy to dismiss her work as exploiting the pain of war, it is to be remembered that she herself is a survivor of it and is not interested in victimizing her subjects. Rather, in Salcedo’s words, “Art can restore the dignity which has been ripped away from the victims at the time of their violent death.” It’s a haunting, disconcerting, and deeply powerful exhibit from an emotive and determined artist.

Author Bio:

Sabeena Khosla is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.