The Art of Al Hirschfeld – The 'Line King' Reigns On

What’s in a line, you might ask. And it wouldn’t be an unreasonable question in response to a comedian’s quip on the stage or a child’s connect-the-dots attempt in his coloring book. But when the hand drawing the line belongs to Albert “Al” Hirschfeld (6/21/1903-1/20/2003), the premiere caricature artist of the 20th century, it’s simply everything.

So distinctive were the portraits from the line king’s pen that celebrities lined up in droves to be “Hirschfelded.” And the roll call is staggering: Charlie Chaplin, Carol Channing, Winston Churchill, Ella Fitzgerald, Jane Fonda, Ringo Starr, Liza Minnelli and Tommy Tune, just to name a few. Over a hundred original drawings and other ephemera from his early work in Hollywood to his latest iconic portraits for The New York Times are currently on dazzling display at the New York Historical Society. It’s a must see for anyone with a nostalgic bone in the body. For the art seeker of high style with substance, it’s a never-to-be-forgotten treat.

Upon first entering, the visitor is greeted by the blinking lights of an old-fashioned marquee. Hirschfeld had a life-long love affair with the performing arts and Louise Kerz Hirschfeld, President of the Al Hirschfeld Foundation, and guest curator David Leopold have honored that obsession. There are constant reminders of the entertainment world throughout, with bold wallpaper blowups of the Great White Way by night. A few rows of theatre seats in a rear corner of the exhibit are an invitation to view a revealing video. Hirschfeld’s working process on a droopy-eyed caricature of actor Jason Robards is shown, along with some salient comments by theatre impresario Joseph Papp, who admits that the great draftsman never made his subjects look “beautiful” but always “interesting.”

His caricatures are almost always drawings of pure line in black ink, into which Hirschfeld dipped not a pen but a genuine crow’s quill. A 1993 profile portrait of Ella Fitzgerald with signature glasses is a continuous swirl of line. His was a total obeisance to the power of the line, which could be interpreted as an intentional move toward the abstract, but never swayed from making his subject the paramount attraction.

As one might suspect, the bushy-bearded master of the pen was hardly quick to elucidate where his talent comes from. “I just do the drawing,” he confessed in the aforementioned video. His was a religion of recognition—a few well-placed lines could signify all one needs to know about a person. He believed that the average man-on-the-street can recognize a person by a physical gesture or a prominent feature, but he doesn’t always possess the ability to express on paper what makes for that recognition.

So how does he do it? “The whole trick is to stay alive,” he tells us, tongue-in-cheek.

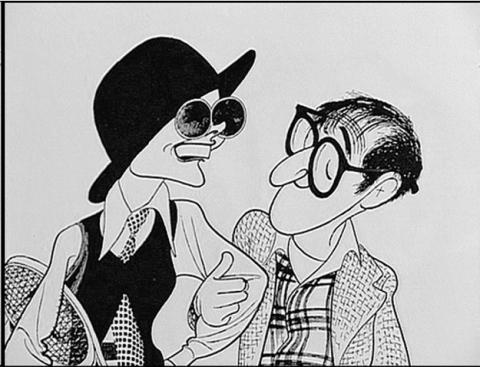

With his creations spanning over eight decades, it’s no wonder this stunning exhibit, aptly entitled “The Hirschfeld Century: The Art of Al Hirschfeld” is arranged chronologically. While his contemporaries were still cutting their teeth on boxes of crayons, the seventeen-year-old art director of Selznick Studios and subsequently MGM, was promoting silent screen stars Laurel and Hardy and soon after the Marx Brothers, among other luminaries. A full color poster depicts the former jolly pair in bed together, Hardy’s bowler cocked over a bed post, with a wallpaper collage serving as a crazy quilt. It’s innocent enough in the rendering but devilishly creative. Another collage from 1932 for A Day at the Races shows the Marx trio, with two triangles of steel wool to represent Groucho’s hairdo. An amusing caption notes that MGM’s hairdressers worked painstakingly to duplicate the image Hirschfeld had conjured up.

But interestingly enough, this precocious St. Louis native had a serious side to his nature. Interrupting his sojourn in Hollywood, he did what so many wide-eyed young artists had done before him: he headed for Paris and London to continue his studies. And judging by the examples on display here, his artistic ambitions paid off.

A rare sample worth a second look is a boldly haunting lithograph, Art and Industry (1931) of pedestrians—monolithic appendages of legs stomping across the picture foreground—while in the background a beggar slumps in a small white pool of light. It was a powerful enough image of the nation’s economic disparities that German expressionist Georg Groz remarked on its mastery. Another image from 1939, Peace in Our Time, depicts a court with faces covered in gasmasks, a noxious swirl of gas rising up from the center of the room. Rejected by the New York Times, it was published by a leftist rag of the time, “New Masses.” An early delicately rendered watercolor of two Balinese women shows a mastery equal to portraitist John Singer Sargent’s in that medium.

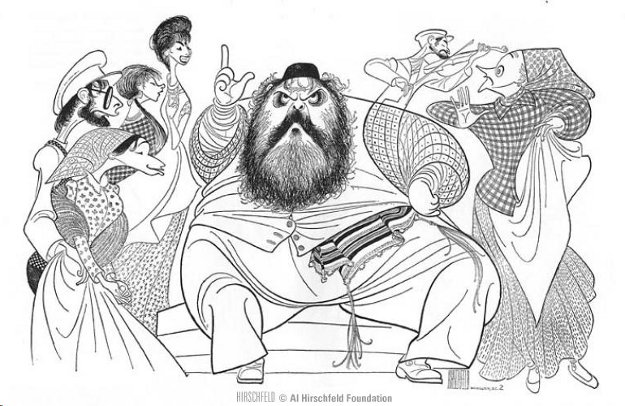

Fortunately for the entertainment world, it wasn’t long before Hirschfeld’s unique talents as a caricaturist were brought to the attention of the New York Herald Tribune and later, the New York Times. The rest is history, as they say. Wandering from wall to wall, down the decades, the exhibit is truly an embarrassment of riches. In addition to his portraits, he did richly detailed cast drawings such as the one from Fiddler on the Roof (1967). The inimitable Zero Mostel, who gave a legendary leading performance in that show, dominates with a signature scowl and bushy brows—not unlike Hirschfeld’s own self-portrait on display. Richard Kiley as a skeleton-like Man of La Mancha (1977) is a stand-out, as is Tommy Tune from White Tie and Tails (2002), his tapping feet a brilliant blur in the bottom frame of the drawing. Whoopie Goldberg, captured in a 1984 sketch from her Broadway show, is all mouth, braids and hands and Jerry Orbach’s ski-shaped nose juts out from a memorable 1980 revival of 42nd Street.

A loving and unexpected touch is an authentic copy of Hirschfeld’s favorite red leather barber’s chair that we’re told in the display notes could go “up, down, swivel and recline.” (The original is housed in the lobby of The New York Public Library of Performing Arts.) It was his favored seat during the decades of his productivity. When I visited, a young girl was occupying the chair, seriously intent on copying one of the caricatures provided.

It’s no surprise that Hirschfeld’s own beloved daughter Nina couldn’t escape from the capriciousness of her father’s pen. Over the years, thousands of his fans hungrily searched each drawing for the girl’s name in his subjects’ wisps of hair or clothing, the number of appearances of her name often listed at the bottom of the portrait. For a time, the artist’s conceit became a national pastime of sorts, so it was a special treat to see her own portrait, “Nina’s Revenge” on view. The “revenge” in the title is meant to be the placement of her parents’ names, respectively Al and Dolly, concealed in her abundant locks.

Such a successful career spent celebrating the celebrated could hardly go unrewarded. In 2002, Al Hirschfeld was awarded the National Medal of Arts. At his death, on January 20, 2003, the lights of Broadway dimmed for the king. Then on June 21st of the same year, the Martin Beck Theatre—an iconic performing site since 1924 on West 45th Street, was renamed the Al Hirschfeld Theatre. And it was only appropriate that his birthplace honored him with a star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame.

Here’s a late in life quote of the artist’s from this wonderful exhibit: “I’m still involved with the mystery of the line and what it can do.” Thanks to the genius of Al Hirschfeld, we can be too.

(The current exhibit will be on view through October 12th at the New York Historical Society, 170 Central Park West, New York, NY 10024. 212-873-3400.)

Author Bio:

Sandra Bertrand is Highbrow Magazine’s chief art critic.