Marc Riboud Captures the Mysteries of Asia in Photo Series

It’s hard to remember that photography wasn’t always considered a true art form. Throughout the 19th century, it was popularized for documentary, journalistic purposes. Though many individuals were manipulating the medium to utilize its expressive capabilities, melding painting with performance, photography was generally considered a lesser art form until modernity really took off in the early-mid 20th century.

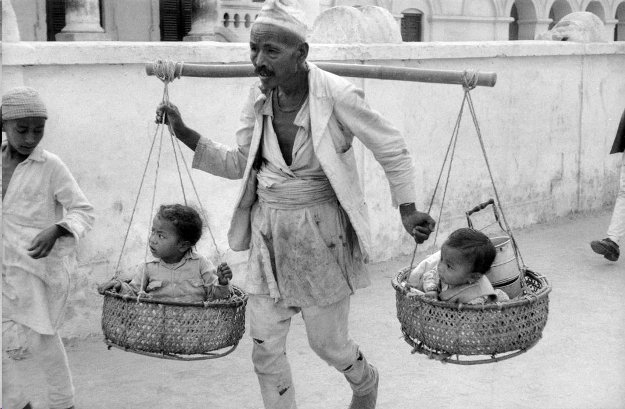

Marc Riboud, whose work from his time in Asia (1955-1958) is now on display at the Rubin Museum in Midtown Manhattan, was part of a group of photographers in the 1950s looking to experience and comment on virtually anything the cultural world had to offer.

While it sounds typical – Western male artist enters “exotic” land to bring stories back home – one must remember that at the time of Riboud’s creations, the metropolitan West, in the fallout of the World Wars, was just starting to gain a real appreciation for what Asia had to offer. Yet Riboud deters from juxtaposing the differences in cultures as a way to highlight both sides’ strengths. Rather, he leans towards the implied and shared banal tendencies. He achieves this through his emphasis on local environments, but more so in his keen awareness of how human beings, as bodies, inhabit the space and of their innate ability to represent it.

This rings true regardless of location. A simple example is his Darjeeling. It is set outdoors with two large trees framing and naturally organizing the picture plane. One of them is leaning in a precarious fashion thereby romanticizing the scene, but what really provides the sentiment are the individuals resting or roaming all with dark umbrellas. Their addition is an underscore to the fogginess that envelops the entire photograph. If this image was devoid of human presence it would read eerie in its haziness and ambiguity. Their clothing, umbrellas, and slight indications of movement give Darjeeling the necessary subtle signifiers of location and atmosphere, elevating the everyday without overstating it.

The understatement is also evident in a photograph that Riboud is present in himself. He is lounging in a large yard with two others in Nepal, having drinks. While a lavish, clearly Eastern styled building is behind them, the focus remains on the quiet moment between the three individuals. Once again, the setting comes secondary to the people in it, and if they were removed the composition would have a much more mysterious air, which is interestingly seen in his photograph of temple architecture. It is staunchly abstract in nature, and thereby one of his more overtly modern productions. However, what Riboud achieves is suggesting a human presence. The rounded shadow in the lower left, darker than the rest, gives the impression of someone walking through the space. Even when humans are not obviously present, Riboud finds a way to meld the geometric with the organic, in this case the spiritual.

While in Tehran, he became fascinated with the relationship between religious/spiritual icons and everyday activities. In a Gym in Tehran is one of his more active works in terms of movement. This gym, as Riboud notes, is “decorated with mirrors, photographs of the athletes, the Shah, and the Prophet Ali.” Riboud captures this moment in time through the glass of one of those mirrors giving it a voyeuristic feel with the multitude of shirtless, robust gym goers. However, going into WWII and thereafter, it was not uncommon in Europe to unite the strength of a nation with the physical strength of its citizens, a famous example being Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia for the Berlin Olympics. Though a different culture and location entirely, Riboud centers in on the global trend of nationalism and the power of the state yet not in a propagandistic style. Ali and the Shah have no presence save for Riboud’s own words about the scene. It removes the individuals from any sort of overt religious affiliation thereby uniting them with that sense of banality Riboud aims to express. Upon deeper examination one can discover differences but they remain trivial.

Also on display, in a similar vein, is a photograph that shows locals witnessing a procession for the new King of Nepal. The geometry is rigid due to the lines of identical windows and balconies, articulated by portraits of former kings. However, the grouping of so many individuals gazing out of the windows gives the composition an audible quality by having their movement highly concentrated. He was hired to officially photograph this event, yet the exhibit correctly addresses the artistic nature of this photograph. When it comes to depicting matters regarding state, he moves away from the wider atmospheric compositions towards condensed groupings of as many individuals as possible, serving as a symbolic cross-section of the everyday. Regardless his work maintains its emphasis that environments do not necessarily define the people. From that perspective he may have been ahead of his time in approaching non-Westerners.

Riboud did produce some photographs, however, that referenced specific cultural constructions. While in India he produced a work showing a sculpture of Kali, the Goddess of Death and Destruction. What’s compelling, aside from her dramatic facial expression and body, is the inclusion of a sleeping boy and dog directly next to it, and how both mirror the God Shiva laying at Kali’s feet. It is another instance of Riboud articulating the relationship between the everyday and the spiritual but in a uniquely Indian manner. It’s also a bit tongue in cheek (and funnily, Kali’s tongue juts out) as she is an important yet dark force -- yet the boy sleeps peacefully beside her. There is subtlety at the root of this photograph. It redefines accepted notions of Eastern cultures from such long-held Western perceptions.

Marc Riboud’s experience in Asia removed the cultures from those confines without eliminating the local landscape, whether he meant to or not. By insisting on the everyday, on the people, his photographs don’t juxtapose the East with the West but meld them through shared experiences while incorporating environment as a secondary signifier. Modern art is understood as an escape from the past, a revolution of sorts that change the way individuals perceive the world around them. While at first glance Marc Riboud’s photographs appear commonplace, that’s exactly where their modern spirit resides.

Author Bio:

Sabeena Khosla is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.