The Paris of Toulouse Lautrec

Henri De Toulouse-Lautrec was born in 1864 to the aristocratic descendants of the Counts of Toulouse, who also happened to be first cousins. Unfortunately for little Henri, that proved to be a prognosis for genetic disorders of the worst kind. By the time he reached manhood at the inauspicious height of 4 feet, eleven inches, he sported a normal torso but the stubby legs of a dwarf. But there was nothing diminutive about his talent. He became one of the most distinctive masters of post-impressionist painting and poster art, almost single-handedly immortalizing Belle-Epoque Paris for all time.

The Paris of Toulouse Lautrec: Prints and Posters, the first Museum of Modern Art exhibition in 30 years dedicated solely to Lautrec, features over 100 examples of work created during the apex of his career. It is a giddy but never glum celebration of the most colorful and notorious characters that inhabited his world and his genius at depicting them. It’s primarily the dancers and aristocratic doyens, the prostitutes, publishers and pleasure-seekers of the night that captured his heart, and subsequently, his brush. If, as Christopher Isherwood’s heroine Sally Bowles so aptly puts it, “Life is a cabaret ol’ chum,” Lautrec and his Montmartre world of light and dark was the start of it all.

Organized thematically from the permanent collection by Sarah Suzuki, associate curator of drawings and prints, the exhibition includes five sections to give the viewer’s eyes and ears a taste of the café-concert and dance hall life, including the famed Moulin Rouge; the performers who became a loving and intrinsic part of his artistic oeuvre; a group of stellar works from his Elles portfolio featuring prostitutes during nonworking hours; a section devoted to his creative circle—highlighting the song sheets for popular music, theatre programs and intellectual reviews—and finally the magic of the city itself through its various venues.

But who were these mysterious and marvelous creatures who served as willing muses?

Often commissioned to advertise famous performers in his prints, the objects of his affections became the perfect blend between subject and style. One example can be seen in his poster Divan Japonais. Jane Avril is seated in the foreground, her pose in all-black attire replete with a characteristically outlandish hat, while in the background singer Yvette Guilbert—known as a diseuse for her half sung-half spoken lyrics—can be seen wearing her signature black gloves. Ironically, Avril suffered from an affliction known as chorea and managed to turn this defect into an advantage by creating a characteristic high-kicking dance.

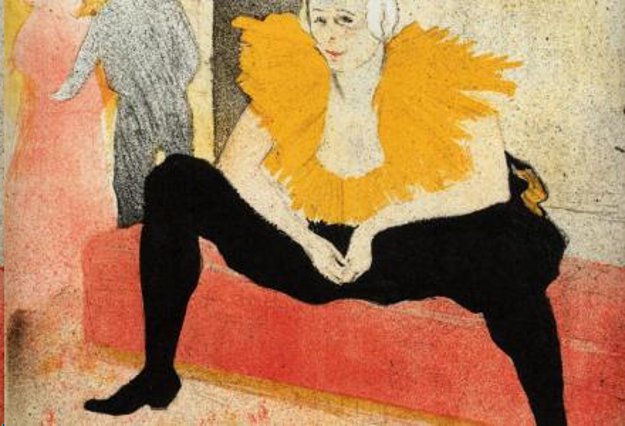

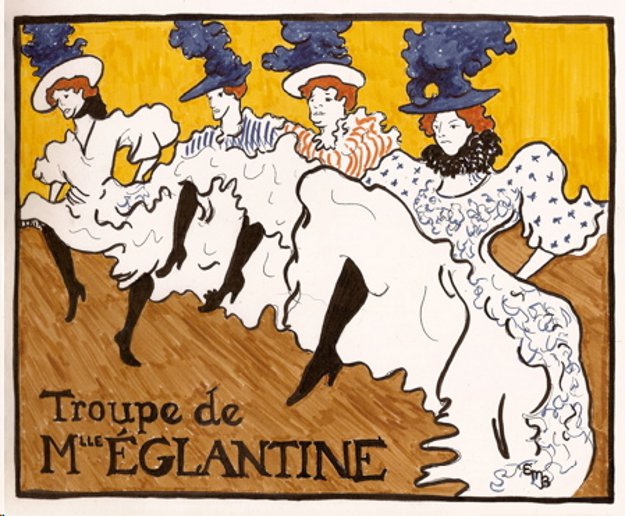

Mademoiselle Cha-U-Kao was another favorite. In The Seated Clowness, she gives us a swaggering, hand-in-pocket pose. In black pantaloons and ruffled top, she serves as an ideal subject for Lautrec’s bold caricatures. Then there was the incomparable Goulue or “glutton,” known as the creator of the French can-can in La Goulue at the Moulin Rouge (1891). Dead-center, she confronts the onlooker. Her arm is hooked possessively about her female companion who is decisively cut from full view, as is another figure on her right. (Lautrec was particularly astute at cropping his images, to heighten the focus of the viewer’s attention on his subject.) The blues and blacks of Lautrec’s palette with his subject’s pale face and décolletage give a dramatic contrast.

If there is any question about Lautrec’s mastery of form and subtlety of color tone, it should be settled once and for all by the set of 12 lithographs titled “Elles” from 1896. He lived for weeks at a time in brothels, fully accepted by prostitutes and madams who were easily wary of their male customers and often, like other celebrated intimates of his circle, lesbians as well. By making the artist their confidante, they did him an incomparable favor. He was able to produce soft, sketchy portraits of such women—languid and lovely at rest or at their bath.

Woman at her Toilette Washing Herself is as tender and touching as the finest work we attribute to Edgar Degas with his dancers or Mary Cassatt’s mothers with their babes. Woman at the Tub gives us a fully-robed figure, bent in half over a large bathing pan. With a few lines and a pale wash of pastels, he has described a scene of universal appeal.

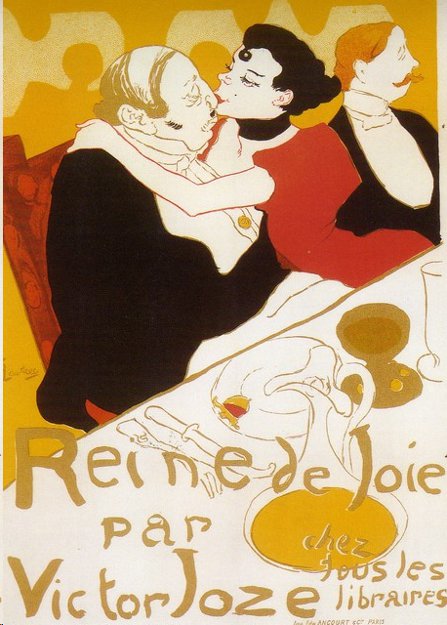

In contrast, Reine de Joie (Queen of Joy), a poster created for a popular novel of the day, we see a blatant display of affection between the alluring young woman at table side, planting a kiss on the nose of her portly benefactor. It’s important to remember that Lautrec’s commissioned posters were meant to be grasped immediately by the viewer, so that a well-placed gesture and high-contrast colors could leave no room for doubt about the intent. It’s not hard to imagine what an indelible impression the cabaret impresario Aristide Bruant must have made—the broad black sweep of his cape from the backside is all we need in Lautrec’s caricature to identify him.

It’s a compact but comprehensive show, with more than a few surprises worthy of close inspection. A particular treat is a 16mm film by Lumiere, entitled “The Serpentine Dancer.” This was obviously inspired by Loie Fuller, who was known as “The Electric Fairy” for her hypnotic dances, really light shows with yards of swirling fabric. Lautrec perfected a lithographic technique called crachis to spatter ink of various color tones to depict the dancer. A not-to-be-missed photograph of the artist shows him seated in Japanese garb, mimicking his affinity for Edo-period Japanese Ukiyo-e prints of performers. Van Gogh and Modigliani were among many artists who were smitten by such styles and Lautrec’s own monograph is based on similar ones on Japanese prints. The Hanging Man is a bold and grisly graphic of an atypical subject—Lautrec had been commissioned to illustrate sensational moments from his hometown of Toulouse.

When Lautrec chose to step outside the haze of absinthe into the outside world (in the catalogue essay Ms. Suzuki admits that “by the 1890s, France had the highest per-capita consumption of alcohol in the world.”), the results were just as dramatic. It’s all here. Through the contour of line and flat colors that he excelled in and brought to exquisite result through the explosion of modern printmaking, he added his own spin on everything from horse racing at Longchamp, promenades on the Bois de Boulogne to the new fad for ice rink antics. Visitors to the exhibit should also be encouraged to give attention to the various vitrines with excellent examples of the work he did for newspapers and periodicals of the day. Le Merliton, for example, shows a humorous illustration from 1893 of a strutting dandy contrasted with a nearby pooch relieving himself.

Sadly, Lautrec’s life was cut short at 36, due in no small part to alcoholism and syphilis—a decidedly deadly recipe. But considering his voluminous output, he can hardly be dismissed as just another self-destructive artist. In his abbreviated career, he managed to produce more than 700 paintings and 368 prints. To paraphrase a popular lyric from Gigi, Lerner and Lowe’s musical valentine to Paris, he managed to light up the skies of Paris with champagne and paint brush in a way we’re unlikely to see again.

Author Bio:

Sandra Bertrand is Highbrow Magazine’s chief art critic.