The Story of the Joads Still Matters, 75 Years Later

In April 1939 John Steinbeck shared with the world the story of the Joad family, a tale (on its most basic level) about an Oklahoma farm family during the Depression and the Dust Bowl, who cram their entire life into an old jalopy in search of richer opportunities in California. The work was adapted into a classic film, directed by John Ford. The novel has inspired music by the likes of Woody Guthrie, Bruce Springsteen and Mumford & Sons. The book won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, helped earn Steinbeck the Nobel Prize for Literature and often appears on lists of the greatest novels. And, most importantly, the work stirred the social conscience into action, similar to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle.

As an historical novel it is rooted in the events that took place three-quarters of a century ago, which may make it seem dated to some readers. But though times have changed, many of the troubles that the Joads confronted are (unfortunately) still with us – economic injustice, the struggle for human worth, corruption. Of equal significance, the work deals with nearly universal themes – human dignity, the struggle for survival and, more than anything else, hope – that make it as pertinent today as it was 75 years ago.

Driving Steinbeck’s narrative was a feeling of righteous indignation, a sense that something was fundamentally wrong in the world that needed to be addressed. In this sense it was a moral novel, shaped largely by the author’s concerns with violent actions taken by employers and police to suppress union activities. Steinbeck once explained that he did not “believe in the liberty of a man or a group to exploit, torment, or slaughter other men or groups.” Rather, he said, “I believe in the despotism of human life and happiness against the liberty of money and possessions.”

But as much as there is a moral involved, which cannot be ignored, it is also notable for its natural prose style, the interchange between social commentary and plot development between chapters, its rich symbolism (drawing heavily from the Bible) and for its well-developed characters, men and women who possess a great deal of resilience and determination to go forward in spite of the obstacles that the social system continuously erects in their path. As Steinbeck said of Woody Guthrie’s music, at the heart, “There is the will of the people to endure and fight against oppression. I think we call this the American spirit.” It was the same spirit with which Steinbeck was concerned in this and many of his other novels, and it was perhaps because of their similar worldview that the work of Guthrie and Steinbeck overlapped so greatly.

It would be nearly impossible to sing all the praises deserved of a monumental work of modern literature such as this in so short an article, for there are many reasons why Steinbeck’s classic still matters today; it is the exploration of a few of these that will occupy the rest of this piece.

The Economics of The Grapes of Wrath

John Steinbeck summarizes in a much neater and more interesting style in this work what Karl Marx – though genius in his own right – rambled on about over the course of thousands of pages. Whereas Marx explains and defines with painstaking detail (sometimes beating to death) terms like alienation, profit, property, surplus value and the reserve army of labor, Steinbeck shows us these things unfolding, sometimes relying on similar, incendiary imagery.

Whereas Marx, in Das Kapital, compares capital to vampires and juggernauts, Steinbeck likens banks (and one could extend this to modern corporations) to voracious monsters. These monsters, to keep alive, employ men to evict families from their homes and drive farmers off their land, for it’s more economical: “One man on a tractor can take the place of twelve or fourteen families.”

But he also explains the dynamics that cause men to work against their own class interests and work for the bank, because they are hungry and need to survive, even if they know that the material gains they receive are only temporary. Steinbeck doesn’t blame one individual, but rather the system, for even some of the “owner men,” he explains:

hated what they had to do, and . . . were angry because they hated to be cruel, and . . . were cold because they had long ago found that one could not be an owner unless one were cold. And all of them were caught in something larger than themselves. Some of them hated the mathematics that drove them, and some were afraid, and some worshiped the mathematics because it provided a refuge from thought and from feeling.

Steinbeck acknowledges that many of the men who work in the service of the banks, or who are owners of the means of production, are not necessarily “bad” people. They merely play the game, even if they hate its rules. They were people who, like most Americans today, possessed very little control over their working lives.

Steinbeck does not define his economic terms, nor does he use Marxist terminology, but for any one with even a rudimentary understanding of Marx, we know when Steinbeck is showing us things like alienation (“[T]he machine man, driving a dead tractor on land he does not know and love, understands only chemistry; and he is contemptuous of the land and of himself”) and when his characters are explaining concepts like the reserve army of labor, an idea that figures prominently throughout this classic.

It’s through a handbill advertising the need for good-paying migrant work that the Joads decide to leave behind their home and head to California’s Garden of Eden. Naïve as they are, like children wanting to see only the good in all people, they initially take the advertisement at face value, only to learn later that the handbills are intended to recruit more laborers than needed, more people, desperate and hungry, willing to work for less than those who came before them.

As one of the characters, Black Hat, explains: “You can’t feed your fam’ly on twenty cents an hour, but you’ll take anything. They got you goin’ an’ comin’. They jes’ auction a job off.” When Pa Joad despairingly suggests that he would take a job at twenty cents if his survival was at stake, Black Hat responds: “Yeah! You’ll do that. An’ I’m a two bit man. You’ll take my job for twenty cents. An’ then I’ll get hungry an’ I’ll take my job back for fifteen.” This is a topic Steinbeck comes back to time and again and it is the basis of this exploitation of labor that drives characters like Black Hat and Preacher Casy to organize.

Steinbeck also shows us the social consequences of having many people out of work, hungry and desperate: crime rates rise and virtuous people do bad things, they become “mean.” And they also become “ashamed” of who they are, as Ma Joad explains.

Throughout, Steinbeck also deals with related topics such unionization and technology’s role in displacing workers from their jobs, ideas also explored by Marx and the Marxists.

While there are some who claim today that Marxism died with the collapse of the Berlin Wall or the decline of the U.S.S.R. (mainly by those who do not understand Marxism), one need only read arguments made by the likes of Richard Wolff, David Harvey, Howard Zinn or Juliet Schor to recognize the continued relevance of Marx’s theories today and, simultaneously, of Steinbeck’s ideas on economics. As income inequality has soared in recent years, with rises in unemployment and stagnant wages for the working-class majority, while unionization rates have plummeted since the 1950s, and in the light of recent events such as the “Great Recession” and Occupy Wall Street, it is not difficult by any means to draw similarities between what Steinbeck wrote about in the 1930s and the world of today.

The Struggle for Human Dignity

Not earning a living wage is undoubtedly an assault against a person’s dignity. When a person wants to work and cannot find a job or cannot survive on the meager wages they earn – as much of a problem in the present as it was three-quarters of a century ago – this does something to his/her feelings of self-worth.

All for the sake of a margin of profit, Muley Graves explains early on, executives “chopped folks in two” and made it so “They ain’t alive no more.” For some this crushed their spirit. For others this was enough to make them “mean like a wolf,” defending what little dignity they had left with all of their life, resorting to violence and theft if necessary.

These people who became mean and ashamed of themselves were men and women – like those whose homes have been foreclosed in recent years, or those today who are buried under mountains of debt – who were forced to leave behind their life’s possessions and the only sense of home that they had ever known because of hard times, or due to changes in the weather and the conditions of the soil. They were people who sold the goods for which they toiled hard for much less than they were worth, people who “were weary and frightened because they had gone against a system they did not understand and it had beaten them.” They were people who moved just to survive. And because they sometimes turned mean or defensive, these were the people that lawmakers wrote laws against to protect the interests of the owning class.

It is because they fight for their dignity, because of this “American spirit” that they possess and defend, that Tom Joad assaults a deputy and later kills one (as he explains, “They’re a-workin’ away at our spirits. They’re a-tryin to make us cringe an’ crawl like a whipped bitch. They tryin’ to break us. Why, Jesus Christ, Ma, they comes a time when the on’y way a fella can keep his decency is by takin’ a sock at a cop. They’re workin’ on our decency”). It is because they fight for their dignity that men like Black Hat and Preacher Casy organize unions, to not only protect what little feeling of self-worth they have left, but to earn what they rightly deserve: decent wages and living conditions that make them feel like humans rather than cattle, that permit them to survive.

To maintain their oppressive rule, it is important for those who run the system to keep the people down. As long as the people forget what it’s like to possess dignity, they cease to expect it. But once they taste again what it means to be treated like a person of worth, as soon as they remember what freedom is, they demand more. And so we find this played out in the government camps in Steinbeck’s novel.

When Tom Joad does a small job for a man named Mr. Thomas, the latter explains to Tom and his co-laborers that the Farmer’s Association, run by the Bank of the West (which sets the going wage for farm labor), plans to create a disturbance in the government camp in order to send in deputies, as police cannot enter and arrest labor ‘agitators’ within the camp without a warrant. “I’ll tell you why,” Mr. Thomas explains, “Those folks in the camp are getting used to being treated like humans. When they go back to the squatters’ camps they’ll be hard to handle.”

And so while there are tastes of what life should offer – nothing glamorous, but humanizing – the system itself tries to keep the migrants beaten and weak, thinking it makes them easier to control, but failing to recognize that fear ferments into anger: “In the souls of the people the grapes of wrath are filling and growing heavy.”

It was this sort of wrath that led to the Occupy movement in recent years, this wrath that brought about the blowback in the Middle East and this wrath that causes deferred dreams to explode, as Langston Hughes writes. The reasons for it may not always be identical, but they are always similar enough.

Self-Worth and the Arm of the Law

When it’s not another human being stripping away one’s self-esteem (shop owners eyeing migrants with suspicion, used car dealers trying to fast-sell junk cars, people who have never known hunger viewing migrants as “others,” deserving of hate), it is the system itself that tries to smother the human spirit. Sometimes it’s commerce, and often it’s the law that holds people down and makes them feel less than human.

As societies progress economically, resorting to violence becomes less common than in the past– though still used occasionally to reinforce order and fear – and instead the state relies on ideology, using tools such as media, schools, laws and the family to maintain the existing social order, a phenomenon recognized by the French philosopher Louis Althusser.

Seventy-five years ago, when Steinbeck’s masterwork first appeared, violence was used much more commonly than we find today to quell labor unrest in this country, though ideology was useful, too. While the National Guard or police may be called in to use force, to both protect the interests of the owning class and to control the working classes and prevent them from becoming unruly, it was not uncommon for laws to pop up to regulate the lifestyles of the common people.

Two obvious examples of this, not explored in Steinbeck’s work, are the prohibition of alcohol and more recently the war on drugs. We could just as well point to public health laws that prevent the homeless from sleeping in certain parts of the city, as if they had many other realistic alternatives available, something Steinbeck does highlight in his book, showing at the same time how this helps line the pockets of others at the expense of those most in need.

When the Joad family pulls up at a place to camp for the night, the following dialogue develops:

The proprietor said, “If you wanta pull in here an’ camp it’ll cost you four bits. . . .”

“What the hell,” said Tom. “We can sleep in the ditch right beside the road, an’ it won’t cost nothin’.”

The owner drummed his knee with his fingers. “Deputy sheriff comes on by in the night. Might make it tough for ya. Got a law against sleepin’ out in this State. Got a law about vagrants.”

“If I pay you a half a dollar I ain’t a vagrant, huh?”

Another character summarizes the law’s view on vagrancy later on, stating: “[A] vagrant is anybody a cop don’t like.”

Similarly, the law regulates the burial of the dead – with some reasonable justification – but with red tape and financial obligations that make it difficult for the working class and the poor. The custom of burying one’s own family members that existed throughout much of human history (and in early America) is juxtaposed with the regulations of the modern world, often with monetary interests involved, something Steinbeck first explores with the death of Grandpa Joad on the family’s journey West:

“We on’y got a hundred an’ fifty dollars. [The law] take forty to bury Grampa an’ we won’t get to California – or else they’ll bury him a pauper.” The men stirred restively . . .

Pa said softly, “Grampa buried his pa with his own hands, done it in dignity, an’ shaped the grave nice with his own shovel. That was a time when a man had the right to be buried by his own son an’ a son had the right to bury his own father.”

“The law says different now,” said Uncle John.

“Sometimes the law can’t be foller’d no way,” said Pa.

As this solemn scene progresses, Tom Joad concludes that “The gov’ment’s got more interest in a dead man than a live one,” a sad truth that is highlighted all the more, much later in the novel, when the newly displaced families in California learn that they have not resided long enough in the state to qualify for relief, compared against the fact (addressed earlier) that many industries receive corporate welfare in the form of subsidies and tax breaks.

The Joads and the other pilgrims in this story recognize over and again that the laws protect not them (“Cops cause more trouble than they stop”), but rather the interests of the owning class, and that in order to survive, they may have to break the law on occasion and may do so at times unwittingly – for what is permissible in one jurisdiction might be illegal in another.

On the American Spirit and Alternative Possibilities

The realities of Steinbeck’s classic may seem bleak on the surface, but so too are the realities with which we are confronted every day. The economic injustices that Steinbeck demonstrates are in many ways still with us. But while John Steinbeck rails against economic oppression throughout, his story is also touching, humorous and brimming with hope, for it shows that in spite of all the obstacles in our paths, the American people are resilient, owing much to their pioneering spirit and even the asceticism of their Puritan forefathers (collectively speaking).

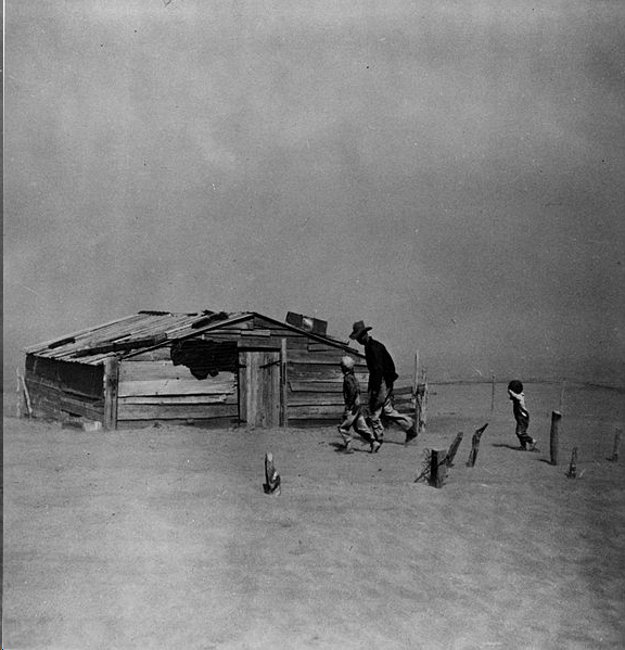

When a Dust Bowl makes their land unsuitable for farming and the banks drive them off their property, they are a people who migrate in search of better opportunities. When a law is written to keep them down, they break it or circumvent it. When the people are prevented from earning decent wages, they organize together and fight for their collective class interests. They are the people who are patient and “go on livin’,” as Ma Joad explains. They are also a people who refuse to succumb to fear, transforming their anxiety into wrath. In short, they are a people who (eventually) fight back, in ways big or small, and who band together in times of need.

Though they might not all be Tom Joads, it is this pioneering, resilient spirit that creates men and women like Joad, who vow to dedicate their lives to combating oppression. When not great revolutionary spirits, they are people who change the world through small acts of kindness: sharing their little food with hungry children, helping families in need when their car breaks down, helping others deal with the death of a loved one. In the face of hate, they sow love.

Tom Joad says at one point, a passage which Woody Guthrie draws on in his songs about the novel’s protagonist:

Wherever they’s a fight so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there. Wherever they’s a cop beatin’ up a guy, I’ll be there. . . . I’ll be in the way guys yell when they’re mad an’ – I’ll be in the way kids laugh when they’re hungry an’ they know supper’s ready. An’ when our folks eat the stuff they raise an’ live in the houses they build – why, I’ll be there.

Before Martin Luther King, Jr. proclaimed that “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere,” John Steinbeck showed us this in action. He made us see that we are all bound together, interconnected rather than atomistic.

As long as there is any injustice in this world (and not only economic oppression) Steinbeck’s novel will be a relevant blueprint for social action, grand or small. And as long as people keep on living, this novel will be a testament to the near universal truths of our world – to the spirit to go forward, to the will to survive and to the belief that tomorrow (with a little collective effort) can be better than today.

Author Bio:

Benjamin Wright is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.