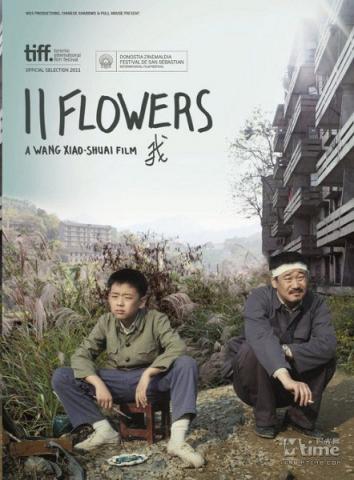

‘11 Flowers’ Deftly Portrays a Poignant Coming-of-Age Story in Rural China

Set in China in 1975 and told through the eyes of an 11-year-old boy, 11 Flowers is many things at once: a coming-of-age story; a thriller; a slice of life from a remote village in the Guizhou province; and a glimpse of the social tension caused by China’s Cultural Revolution. Thoughtful and quietly poignant, the film manages all these elements beautifully, without allowing its young central character to be eclipsed by the events surrounding him—a balancing act few directors can carry off with success, but which Wang Xiaoshuai has mastered.

Wang Han is a typical boy living in the Guizhou Province. His mother works in the local factory; his father is an actor who is away much of the time at a university in Shanghai. Wang Han is very much of his time and place. He goes to school and hangs with a coterie of boisterous and irreverent boys his age, who run a bit wild through the village when not doing lessons or chores. Mom is loving and dedicated, but quick to anger and not shy with a smack. Wang Han’s intellectual father encourages his son to paint, to foster independence and a love of art. Times are not especially prosperous: meat is a treat and the need for a new white shirt (Wang Han has been chosen as Gym Leader) poses a financial burden.

A series of strange events mark the divide between youth and young adulthood for Wang Han. An older classmate, Juehong, collapses outside of class. The dead body of a factory official is found by the river. There’s gossip over dinner and in the bathhouse. School officials warn the students that a murderer is on the loose. Wang Han’s father has to leave his job after being involved in a riot. We see these events as Wang Han sees them: from glimpses caught out of corners and shadows, and in whispers and rumors from the adults, who barely notice the kids are underfoot and don’t imagine that they understand. Like 11-year-olds everywhere, they grasp more than their elders think, and less than they themselves realize.

When Wang Han loses his precious white shirt in the river, he is swept along a dark path involving a killer, a scandal and a society starting to buckle under the weight of its myopic, stubbornly unyielding political system. Quiet, pensive Wang Han watches as these tragic events unfold, and begins to grow up before us.

Wang Xiaoshuai has an instinctive understanding of youth culture, as he demonstrated in 2001’s Beijing Bicycle and in 2005 with Shanghai Dreams (which won the Jury Prize in Cannes that year); he brings that same magic touch to 11 Flowers. From familial interactions to the camaraderie and rivalry amongst boyhood friends to the first stirrings of sexual awareness, there’s a real tang of lived experience about the film. The amateurish, man-in-the-street style he tends to use (and which partially defines him as a Sixth Generation Chinese filmmaker) also feels right here; this is a very personal (and possibly autobiographical) tale about a young person’s emotional maturity in a provincial town. Internal landscapes are favored over sweeping vistas, making Wang Han’s journey all the more affecting.

As 11 Flowers comes to its sad conclusion, we are reminded that the changes that rocked China after the death of Mao Zedong in 1976 were only partly the result of the violent upheavals of the Red Guards and other factions. The personal tragedies of the average citizen left their own smaller, but possibly more resonant impact as well.

Author Bio:

Nancy Lackey Shaffer is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.