Julian Barnes Embarks on Literary Analysis of Influential, International Writers

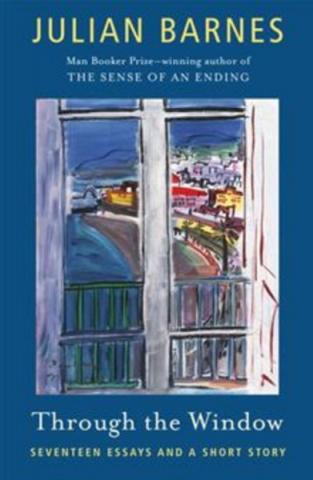

Through the Window: Seventeen Essays And A Short Story

Julian Barnes

Vintage

227 pages

Julian Barnes knows France—its culture, cuisine, topography—and its curious relationship to England. In an earlier book, Something to Declare, and in his new collection, Through the Window, France and the French are either in the forefront or background of many of these witty, piercing and erudite essays. Whether he’s tracing the influence of the French countryside on Ford Madox Ford (“Ford and Provence”), analyzing the complexities of translation (“Translating Madame Bovary”) or offering a fresh look at Rudyard Kipling (“Kipling’s France,” “France’s Kipling”), Barnes delivers valuable insights into a culture and people who have risen above the desperate inequities of the past century:

“Perhaps what [Kipling] most admired in France was what he thought his own country could do with more of. Work, ethic, thrift, simplicity; ‘the acceptance of hard living which fortifies the moral interior as small pebbles assist the digestion of fowls’ … Kipling believed that a period of enforced military service promoted not only civic virtue but also a fundamental seriousness of mind which he felt his compatriots lacked. A Frenchman once said to him: ‘How can you English understand our minds if you do not realize those years of service—those years of service for us all? When we come to talk to you about life it is like talking about death to children.’”

Julian Barnes knows literature too, and as author of many novels and short stories (including the Man Booker Prize-winning novel, The Sense of an Ending), he is enormously perceptive about the craft of writing. Reading is deeply important to him; when he chooses to review the works of others, it’s generally with an air of appreciation for the dedication and skill they bring to the elusive art of fiction.

In one of the longer essays, “Remembering Updike, Remembering Rabbit,” he savors the last of the great writer’s stories and makes a strong case for the Rabbit Quartet as “still the greatest postwar American novel.” As he notes: “Updike always treated the reader as a joint partner in the artistic process, an adult equal with whom curiosity and delight in the world were to be shared.”

Perhaps Barnes’ greatest contribution to the form of literary essay is his unique ability to commingle critical judgment with snatches of autobiography and snippets of travel writing. The result is nearly always wry, clear-eyed and delicately composed.

The best example is the first piece in Through the Window about the late British writer Penelope Fitzgerald. The essay starts with a personal recollection (“Her manner was shy and rather distrait, as if the last thing she wanted was to be taken for what she then was: the best living English novelist”) and continues through a precise account of Fitzgerald’s uniquely back-loaded career. She began publishing her award-winning novels relatively late in life, choosing subjects that in their ambition and scope baffled those who knew her:

“They are written far from her obvious life, being set, respectively, in 1950s Florence, pre-revolutionary Moscow, Cambridge in 1912 and late-18th-century Prussia. Many writers start by inventing away from their lives, and then, when their material runs out, turn back to more familiar sources. Fitzgerald did the opposite and by writing away from her own life, she liberated herself into greatness.”

With great affection, Barnes examines the “benign wrong-footedness” of her work, and how in modest and understated prose, this wrong-footedness “culminates in scenes where the whole world, as physically experienced and relied upon, is given a sudden tilt.” Steadily, methodically, he makes the case for a re-examination of this largely ignored novelist’s work. The reader finishes “The Deceptiveness of Penelope Fitzgerald” eager to experience for the first time (or to revisit) The Blue Flower and The Beginning of Spring. A literary critic can provide no more valuable service than to rekindle interest in works that deserve to be read long after the author’s death.

This unquestioning faith in the written word permeates every piece in Through the Window. Regardless of the ease or difficulty of any given work of fiction, Barnes contends, readers embark on a voyage of discovery into worlds beyond their own, a virtue in and of itself:

“Novels are like cities: some are organized and laid out with the color-coded clarity of public transport maps, with each chapter marking a progress from one station to the next … Others, the subtler, wiser ones, offer no such immediately readable route maps. Instead of a journey through the city, they throw you into the city itself, and life itself: you are expected to find your own way.”

Author Bio:

Lee Polevoi, Highbrow Magazine’s chief book critic, is the author of a novel, The Moon in Deep Winter.

Photos: Barnes and Noble; David Rodrigues (Flickr, Creative Commons).