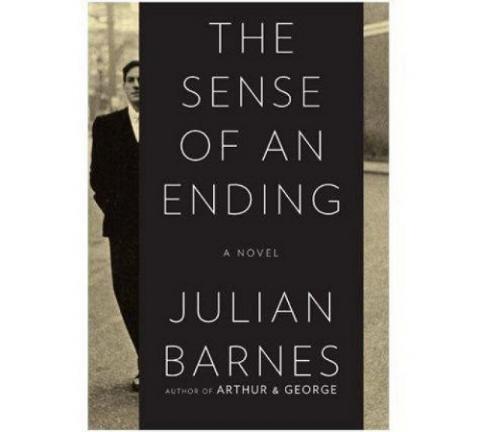

Julian Barnes and the Minefields of Memory

The Sense of an Ending

Julian Barnes

Knopf

163 pages

In The Sense of an Ending, winner of the 2011 Man Booker Prize, Julian Barnes has achieved an oddly remarkable thing: He’s written a long novel in the form of a short one. It spans the lifetime of Tony Webster, a late-middle-aged Englishman of no special distinction who receives a mysterious bequest of £500 and is prompted for the first time to reflect on how his event-filled adolescence has influenced the outcome of his adult life.

More than 40 years ago, Tony was part of a trio of bookish and precocious schoolboys, whose clique was invaded by Adrian Finn, “a tall, shy boy who initially kept his eyes down and his mind to himself,” but who increasingly came to dominate the group. While Tony and his friends regarded themselves as a cut above the others in school, he soon understood that Adrian was something different:

“We were essentially taking the piss, except when we were serious. He was essentially serious, except when he was taking the piss. It took us a while to work this out.”

Eventually, Adrian goes on to Cambridge and the promise of a brilliant career. Tony attends Bristol and embarks on a tormented affair with Veronica Ford, a young woman who thwarts his attempts at seduction. “But wasn’t this the sixties?” Tony (the novel’s narrator) asks rhetorically. “Yes, but only for some people, only in certain parts of the country.”

Upon being invited to Veronica’s family home in Kent, Tony looks forward to a clandestine sexual encounter with the object of his desire—an expectation cruelly thwarted in the course of an especially humiliating weekend. In this sequence, Barnes presents us with a master class in scene-setting, dialogue and character portrayal, so concise and off-handedly brilliant as to appear something any writer can do. It most assuredly is not.

Subtly patronized by Veronica’s father (“large, fleshy and red-faced”) and considered a diversion by her brother Jack (“He behaved towards me as if I were an object of mild curiosity, and by no means the first to be exhibited for his appreciation”), Tony is surprised to find common ground with Veronica’s mother, who offers a tidbit of advice that will echo down through the decades:

“Have you lived here long?” I eventually asked, though I already knew the answer.

She paused, poured herself a cup of tea, broke another egg into the pan, leant back against a dresser stacked with plates, and said, “Don’t let Veronica get away with too much.”

I didn’t know how to reply. Should I be offended at this interference in our relationship, or fall into confessional mode and “discuss” Veronica? So I said, a little primly, “What do you mean, Mrs. Ford?”

She looked at me, smiled in an unpatronizing way, shook her head slightly, and said, “We’ve lived here ten years.”

His affair with Veronica, such as it is, reaches consummation only once and only after they’ve split up. Soon thereafter, she and Adrian become romantically involved. And at age 22, Adrian kills himself in his flat in Cambridge.

Now, decades later, Tony is a retired arts administrator, divorced (from Margaret, a sensible and far more reasonable woman than Veronica) and the father of a daughter, Susie. His quiet, organized existence is wrenched away when he learns of the death of Veronica’s mother, who has left him £500 and a diary once belonging to his late friend and suicide, Adrian Finn.

A letter Tony wrote as a young man, upon first learning of Adrian’s and Veronica’s affair, resurfaces around this time. The document, so at odds with the past as he’s presented it, calls into question everything we’ve read and learned up to this point. From here on, The Sense of an Ending becomes a different story altogether.

Unreliable narrators have entertained and perplexed readers as far back as Tristram Shandy in 1759. More recent novels as varied as Ford Madox Ford’s The Good Soldier and The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro offer up glittery jewels of first-person narration, in which voice is everything. Readers are either seduced by the narrator or they’re not. And regardless of the subject matter, such works take on the aspect of a detective novel, inviting us to assess for ourselves how much of what we’re being told is fictional “reality” and how much has been subsumed and reinvented in the narrator’s mind. The Sense of an Ending is a fine newcomer to this tradition.

At the same time, use of the unreliable narrator can be frustrating and distracting – frustrating, since we know that what’s on the page may be glossing over the “facts” of the story (thereby keeping us at something of a distance from events) and distracting, since we must continually stop to gauge what is “true” (in the context of the story) and what isn’t. Only the most accomplished examples of this technique, as in Ishiguro’s tone-perfect novel, manage to skirt this obstacle.

The Sense of an Ending isn’t quite as successful, partially because, after so vividly recounting his early years in the novel’s first half, Tony takes up a fair amount of space theorizing about the nature of memory and how we grapple with who we were and what we’ve become. This slows the pace considerably and at times gives way to Barnes’ tendency to inject miniature essays within his fiction – a trait evident throughout his long, productive career. It’s all perfectly captured in Tony Webster’s even-handed style of narration, but frustrating nevertheless.

Time, memory, grief and death are subjects encountered again and again in the fiction of Julian Barnes, and in his quasi-memoir, Nothing to be Frightened Of. What’s most appealing in his work is the light touch, deft characterization and often very funny way in which he dramatizes these themes, and this latest novel is no exception:

“How often do we tell our own life story? How often do we adjust, embellish, make sly cuts? And the longer life goes on, the fewer are those around to challenge our account, to remind us that our life is not our life, merely the story we have told about our life. Told to others, but—mainly—to ourselves.”

This is a writer who pays attention to every word, every sentence, every paragraph, and is always worth reading.

Author Bio:

Lee Polevoi, the author of The Moon in Deep Winter, is completing a new novel.

For Highbrow Magazine