Jasper Johns at The Whitney: The Magician at Play

In the mid-1950s, Jasper Johns had a dream about an American flag. Shortly thereafter, he painted one of his first attempts at this iconic image, which was then discovered by famed dealer Leo Castelli and subsequently purchased by Alfred H. Barr, then director of the Museum of Modern Art. Maps, targets, letters and numbers followed. By the ‘60s, Johns was to the average man or woman on the street, the artist who painted flags.

Of course, the trajectory of celebrity and greatness is more complicated. Even in the 21st century, understanding the man behind 60 decades of his works remains nearly impossible. In Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror, displaying as well as interpreting his artistic output is more to the point, and one that the Whitney Museum in New York under chief curator Scott Rothkopf and Carlos Basualdo, senior curator of contemporary art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, have made their mission. It’s a monumental one.

Split between the two world-class museums, there are enough examples of the artist’s curiosity and versatility to satisfy his fans.

Enough that a journey to experience the sheer number of paintings, prints, and sculpture on display in both venues is an option, but hardly necessary to enjoy the full spectrum of Johns’ ideas and obsessions.

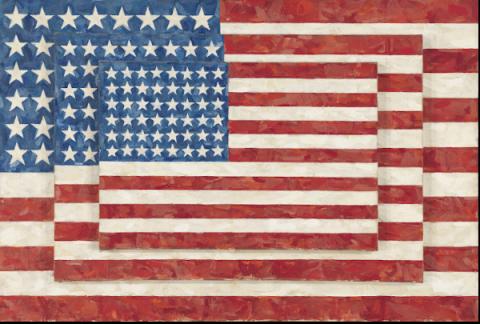

The flags are a good enough place to start. To paraphrase Gertrude Stein, a sometimes, frustrating stylist in her own right, “a flag is not just a flag is not just a flag.” His encaustic creations employ brushstrokes in pigmented, bumpy wax, a technique rare at the time. Representational (an American flag), the imagery incorporating stripes—and in his Targets series, circles that hark back to the abstract—what you see is not what you get. The flag is capable of resonating within us the rawest of emotions.

When Flag (1954-55) appeared on the scene, the Cold War was raging, then during the Vietnam War, when flag-burning became a public phenomenon, Johns’ manipulation of such images seemed almost commonplace. In his words, “They carry an incipient weight in our personal and public conscience.”

What Johns had done with his art/life mix-up was to turn Abstract Expressionism on its head. According to critic Holland Cotter in the New York Times (September 24, 2021), Johns’ flags had “changed forever American art. They made gestural abstraction begin to look operatic and sappy and uncool.”

If Philadelphia gets the lion’s share of “Numbers” from the artist’s oeuvre, the Whitney memorializes the flags and maps in their own expansive gallery. With 3 Flags (1958), the optics hypnotize: three blocks diminish in size from the foreground. A gigantic multicolored map of the U.S. blurs the boundaries of state lines, at once a seemingly careless rendition but on the opposite wall, the same map of formidable size in dark charcoal shades. Color or the lack of it suddenly takes on an emotional charge to the viewer. Target with Four Faces (1955) is a powerful encaustic piece. The spiral target itself is the central focus yet the anonymity of the row of heads jutting forth from the top of the target is unsettling. The artist has managed to line them up like decoy ducks at a carnival.

In 1961, the long-term romantic relationship between artist Robert Rauschenberg and Johns ended, giving rise to a string of grey-toned paintings that put an end to the notion of his artworks signifying objective indifference. The complexities of the man himself were now in high relief. One of these darker works is stenciled at the top with the word “Liar.” Words became fair game, along with any other imagery life and memory provided.

Born into a broken home on May 15, 1930, in Augusta, Georgia, Johns was an early victim of life’s uncertainties, shuttled between various relatives in South Carolina, arriving in New York as a young man of 25. After studying briefly at Parsons School of Design, a stint in the Korean War in Japan followed. His return to New York and the encounter with Rauschenberg (well on his walk to painterly fame) changed his destiny. When art dealer Castelli entered their downtown studio, he found Johns’ flags and other miscellany “an incredible sight ... something one could not imagine, new and out of the blue." He offered him a solo show on the spot.

The gay subculture of the day had its stars and Johns found friendships among the brightest in that firmament. The year of Johns’ breakup, he painted a darkly moving work, In Memory of My Feelings – Frank O’Hara. The poet in question, a central figure in Johns’ circle, died young from a tragic accident on the beach. Another arresting work on paper, Diver (1962-63) is an homage to Hart Crane, who jumped to his death from a ship. A fascination with Marcel Duchamp led to a shadowy interpretation of that artist in another work.

Defined by some as a progenitor of Pop Art, it’s not surprising that the artist’s bronze sculpture of a Savarin coffee can with brushes, as well as the accompanying prints take center stage in one installation. Surely Andy Warhol, an artistic contemporary and a genius at interpreting mass consumerism, found inspiration in that ubiquitous coffee can.

The most whimsically delightful painting for me is Montez Singing (1989), a surreal depiction of his step grandmother. Two eyes are placed at stray edges of the canvas, a squiggle of a nose that could be a stand-in for a cloud and a ripe lipstick mouth serves as a mountain range at the bottom. A small inset of a sailboat is reminiscent of “Red Sails in the Sunset,” which she sang to the young Johns.

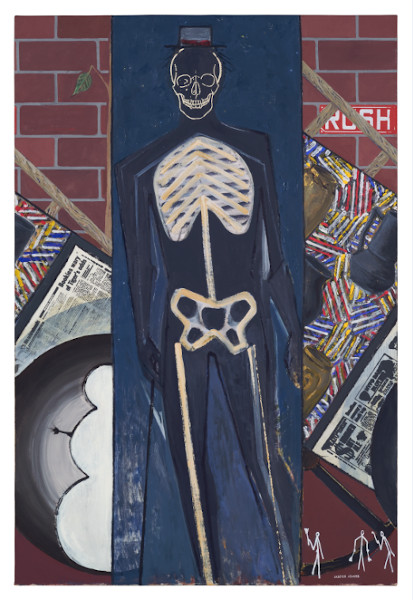

Death as a theme has a place in the artist’s obsessions. Later paintings depict skeletons as part of the imagery with a lightheartedness that makes one think the artist at 91 has come to terms with the issue of mortality. One work places the skeleton over an original silhouette of the artist from his own shadow. Another earlier and more somber image is based on a 1965 war photograph by Larry Burrows with Marine corporal James Farley crumpled in grief over the death of a comrade.

A love of Japanese art and life following his military service led to a trip to that country in 1964. An increased fervor for printmaking was shared with friends there, and installations in both museums highlight this lifelong interest and relationships with major print houses around the globe.

Strolling through this massive exhibition, retracing my steps more than once, I was struck with the myriad ways art plays with the mind, and in some instances, the emotions. But as celebrated as Jasper Johns is, he remains a mystery to his onlookers and many of his critics. A recipient of the National Medal of the Arts in 1990, and the Medal of Freedom in 2011, one of the highest-paid artists in many a given year, he leaves works that mystify, then exits, leaving us to ponder what other tricks he will pull out of the hat.

Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror runs through February 13th at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Author Bio:

Sandra Bertrand is Highbrow Magazine’s Chief Art Critic.

For Highbrow Magazine

Images (courtesy of The Whitney Museum):

--Three Flags (1958)

--Target With Four Faces (1955)

--Map (1961)

--1964--Ugo Mular

--Untitled (2018)