Alice Neel -- a Collector of Souls – at the Met

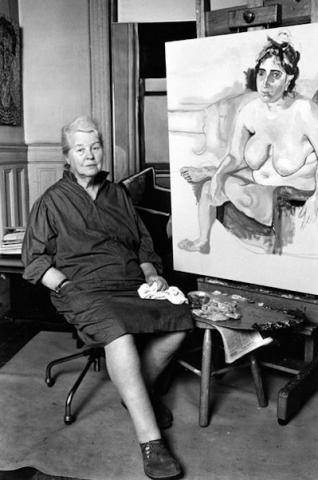

I’m sure we’ve all heard the expression “S/he’s a people person.” Alice Neel's long overdue retrospective, People Come First, is currently drawing hordes of visitors at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It’s no surprise, considering she based her entire life and career around the intimates and strangers that surrounded her. Every class, race, and gender came under her razor-sharp gaze. And no human being encountering her subjects comes away unscathed.

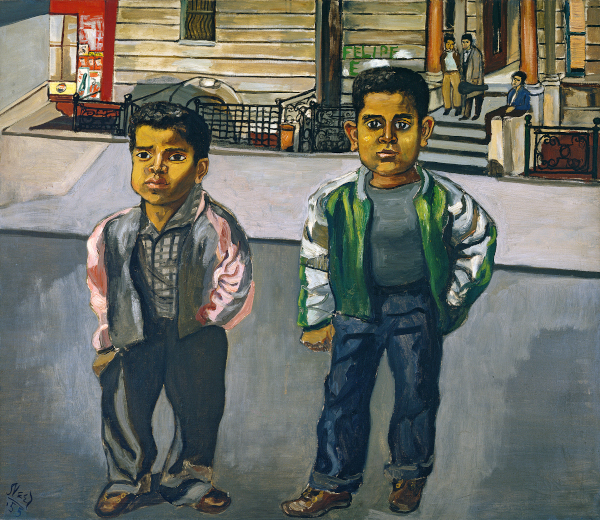

Born in Merion Square, Pennsylvania, in 1900, Neel was obsessed with capturing the turmoil of her times. She was convinced that “people’s images reflect the era in a way that nothing else could.” True to this “anarchic humanist” as she defined herself, she depicted labor organizers like Pat Whalen (1935), neighbors from her Spanish Harlem days like Puerto Rican Girl in a Chair (1949), Georgie Arce (1955) wielding his rubber knife in defiance, and the poignantly wary Two Girls (1959), among many others. (With The Black Boys (1967), The New York Times featured a touching story of one of its surviving subjects. Toby Neal spent decades trying to track down this iconic painting he and his brother posed for over several days, enjoying the snacks the artist provided for them.

What becomes evident in confronting Neel’s earliest subjects is her singularly uncompromising style. Often posing her subjects nude in a frontal position with limbs boldly outlined, occasionally distorted for effect, they dare us not to look away. The total effect of this decisive, unsentimental treatment of our shared imperfections is daunting and unforgettable.

There are no more powerful and unforgiving images than in her maternal portraits. The pregnant body holds sway in several depictions, such as Margaret Evans Pregnant (1978), befuddled in her advanced state. Pregnant Julie and Algis (1967) presents us with its pregnant subject lying nude alongside her fully dressed husband, his arm slung nonchalantly over her shoulder. Mothers with babies figure large in her oeuvre, with the most tragic example, Carmen and Judy (1972). It portrays Neel’s housekeeper, holding her emaciated infant daughter who would die weeks after the painting was completed. A clever juxtaposition by the curators Kelly Baum and Randall Griffey in this section is van Gogh’s painting of Madame Roulin and Her Baby (1888). It fits in perfectly and could be mistaken for one of Neel’s own.

Celebrities played their part, obviously agreeing to the artist’s terms beforehand. One of the most dominant among them is Andy Warhol himself from 1970. Recovering from a near-fatal gunshot wound from feminist Valerie Solanas, his scars in his words “as wrinkled as a Dior dress,” he is naked from the waist up—eyes shut, a living testament to the absurdity of the times.

Art dealer Henry Geldzahler puts in an appearance, his pinky ring predominant in the foreground, a babyish pout on his lips. (Neel’s portrait is more refreshingly revealing than the formal objectivity we see in David Hockney’s portrayals of his friend.) Wryly provocative, transvestite Jackie Curtis with pal Ritta Red huddle together, Jackie’s toe protruding from a ripped stocking. Conversely, the same Jackie is portrayed as a boy, looking as all American as a Norman Rockwell subject.

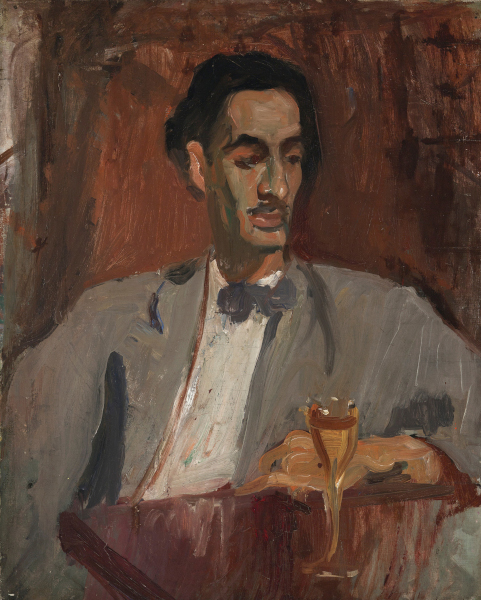

If many visitors are drawn to the high-profile and lesser-known subjects that put the Neel style of portraiture in stark relief, there are other canvases that reflect the prevailing draw of social realism during her Greenwich Village days in the early 1930s. Familiarity with members of the Communist Party, its offices only a short walk from her residence, resulted in a spate of left-leaning sitters, like poet Kenneth Fearing and playwright Alice Childress.

Her painting Uneeda Biscuit Strike (1936) is a darkly dynamic street scene, with demonstrators falling under a regiment of mounted police while sidewalk witnesses stand rapt at attention. Another street scene, Nazis Murder Jews from the same year features a line of marchers stretching into the night’s infinity, with the ghostlike faces in the foreground sporting the eponymous placard. Neel was obviously influenced in such depictions by the prevailing art of the day, with the sober realist tones of Reginal Marsh and even Jacob Lawrence at play.

Feminism played a key role in Neel’s self-image. She viewed herself as a second-class citizen but rather than joining the marches she internalized her struggle. In a 1979 interview in Night, she celebrates men in a brief poem, but characterizes women as “sad, sour, dry with red and shiny knuckles.” If her political embrace of the leaders of second-wave feminism was not always clear, her portraits of the likes of Kate Millet, Adrienne Rich and Faith Ringgold hold their own weight.

Adversity was Neel’s middle name. Her free-spirited nature was quick to collide headlong with domestic disasters at every turn. If her two-year stint in Cuba and an early marriage to Carlos Enriquez was fraught with troubles, the death of a first infant daughter to diphtheria almost broke her spirit.

When Enriquez fled back to Cuba, he took her second daughter Isabetta with him. A nervous breakdown led to the expressionistic Well Baby Clinic (1928-29), a harrowing depiction of a hospital clinic that could rival any of George Grosz’s caricatures.

One of the most magnetic portraits in the show is the nude Isabetta (1934-35). She’s a proud girl, her arms placed firmly on her hips, her eyes insolently fixed on the viewer. Alhough such unabashed child nudity was considered indecent by the museums of the day, it remains one of the most striking images in the show. Years later, Neel would recreate the painting, which was destroyed along with 350 artworks by ex-lover Kenneth Doolittle.

A second image that must have haunted the artist was that of the ailing TB-ridden brother of another yet another paramour, Jose Santiago Negron. In T.B. Harlem (1940), the young man’s eyes stare passively outward from the dark interior, as he holds a white bandage over his breast. Neel’s fixation with family members would continue throughout her life, with portraits of her sick mother, her two sons at various ages, and ultimately the nude image of Neel herself from 1980, paintbrush in hand, her pale skin contrasting with a blue, striped armchair. In the only self-portrait the artist created, she sits before us—an unapologetic, bespectacled figure triumphant in all her flaccid, fleshy splendor.

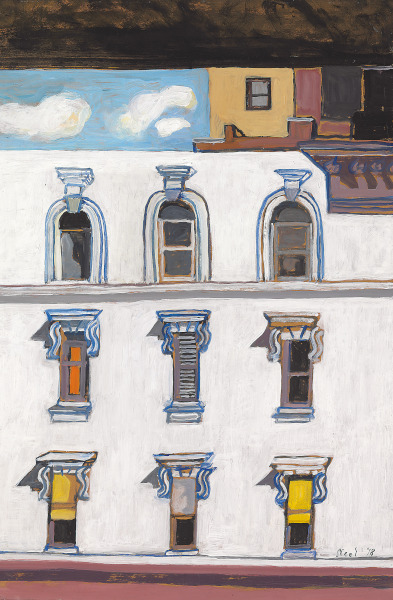

Abstraction did not go unnoticed by the artist. Her ability to simplify, flatten, and distort her recognizable subjects showed her advanced skills as a technician. It was only her unwillingness to totally abandon a figurative approach that kept her marginalized by the prevailing non-objective, male-dominated, mid-century art world.

Not surprising, however, to see Neel skirt the boundaries of both worlds. Her Harlem River at Sedgewick Avenue is a jumble of physical shapes—their varied angles, the contrast between the foreground of green and the river itself cutting across the amorphous foreground, show a mastery of composition. Cut Glass with Fruit (1952) gives dominance to two bowls, one brandishing its fruit while the other stands empty, the background fading away in pale blues with a partially visible stack of books. It is the sureness of intent that grabs the viewer, not unlike a still life by Matisse. No explanation necessary.

Why does Alice Neel and her subjects stay with us—heightening our sensibilities, refusing to fade into some bygone time? Like many great artists, she humanizes our world in the way only she can. Museums worldwide are filled with beautifully manicured portraits of their subjects. What Neel gives us is ourselves, in all our unembellished truths, if we are only willing to look.

The Alice Neel exhibit is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through August 1, 2021.

Author Bio:

Sandra Bertrand is Highbrow Magazine’s chief art critic.

For Highbrow Magazine

Image Sources:

--Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

--Lynn Gilbert (Wikimedia, Creative Commons)