Confessions of a Former ‘New York Times’ Washington Correspondent

PROLOGUE

The Leak

Journalism, as concerns collecting information, differs little if at all from intelligence work. In my judgment, a journalist’s job is very interesting.

—Vladimir Putin, Russian president

Secrecy, being an instrument of conspiracy, ought never to be the system of a regular government.

—Jeremy Bentham, English philosopher

WASHINGTON BUREAU, THE NEW YORK TIMES,

AUGUST 1972

The elevator performed its ritual ping at the eighth floor as I ran across the hall and into the newsroom.

Good, Bob Phelps was at his desk. Phelps was my editor. He was short, slight, gray-haired, and taciturn. He rolled a miniature wooden dental stake around in his mouth, working away at his teeth during one of his habitual dental stimulator sessions. Shortly after he had eaten lunch, his custom was to part his shirt carefully between the buttons and look with care at a red dot on his small white stomach. He would also take out the trusty wooden pick and diligently stimulate those pesky gums.

“Let’s go to your office right now,” I said. I picked up a reporter’s notebook, handed it to him, and told him to bring a pen.

Bob’s idea of showing emotion was to smile slightly, showing the well-stimulated incisors. He didn’t smile. No doubt he thought, the kid’s acting up again, but . . . it’s his last day, and it was. I was thirty-one and had been a reporter at the Times for four years, but I was leaving to go to Yale Law School. Except I’d just gotten a scoop and I couldn’t walk away from it.

I dragged him to the small office he had next to Max Frankel’s big office. Frankel was bureau chief at the Times. Along the way I picked up a desk-size tape recorder. Once we were inside, I closed the door. He sat at the edge of the small print couch. I paced. Someone came through the door. Bob dealt with whoever it was.

I closed the door again and Scotch-taped a Do Not Disturb sign to it. I started the small tape recorder, made sure the tape was whirling, and urged Bob to take notes in the spiral-bound, tan-covered notebook I had handed him.

I was sputtering. “You cannot attribute this to the source,” I warned, “but I just had lunch with Pat Gray and. . . .”

I told him the story of my afternoon when the gray-suited man with enormous cauliflower ears walked through the door of the posh French restaurant and spotted me, his young lunch companion, seated on a red banquette against the wall. Louis Patrick Gray III, the acting director of the FBI, waved off the maître d’. Tall and unassuming, with inviting nonchalance, he headed for the table. I knew Gray was naïve for a Washington official, a former submarine commander turned lawyer. He’d invited me to lunch. He sat down, lanky legs tucked under the white tablecloth, and greeted me warmly. I was dressed as usual in chinos that could stand a pressing and a Harris Tweed jacket left over from college.

He wasted no time telling me that the attorney general and the president were involved in a crime. This was August 1972, just two months after the burglary in which five men had broken into the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee at the Watergate office complex. He was telling me this in a restaurant filled with diners, not in an underground garage.

Gray seemed oblivious that what he was saying, openly, in a crowded power restaurant might be overheard. He used no code names, no secret handshakes, and made no effort to sugarcoat. There was just the bright Washington sunshine streaming in through big windows and steak frites on our plates, just a casual lunch between the acting director of the FBI and a Times reporter. This was months before Woodward and Bernstein’s revelations on Watergate and a cover-up that led, the director disclosed that day, through the attorney general to the White House.

I struggled hard to remain stony-faced in the French restaurant and likely failed awfully. I managed to say nothing, but must have appeared to Gray, and any other diners who happened to look, shaken, or, as the French say, bouleversé—turned upside down.

That day Gray told me—and I told Bob—about a guy later identified as G. Gordon Liddy, an FBI agent until a decade earlier and chief operative in the scandal, and about Donald Segretti. He named Segretti. When he intimated over the entree that the wrongdoing went further, I leaned against the wall behind the banquette. I looked at him and asked in astonishment, “The attorney general [is involved]?”

![]()

He nodded.

“The president?” I asked.

Gray looked me in the eye and made no comment. In other words, confirmation. I slumped back, appetite gone. He seemed to me to be a stand-up conservative submariner turned Republican politician, if naïve in a way not typically permitted in Washington, DC. I couldn’t imagine why he was telling me this. I couldn’t take my notebook out—at least I thought I couldn’t. Too many people would have noticed the acting director of the FBI with some youngster taking notes. So I struggled to remember names: Segretti—spaghetti. Mnemonics are the last refuge for those with notebooks secreted in pockets.

We finished eating. On the pavement in front of the restaurant, I told Gray I was leaving the Times for Yale Law School the very next day. He hadn’t known, and he seemed more shocked about my leaving than I was about the story he’d just told me. Or perhaps he just didn’t try to mask his surprise the way I did.

I hurried back to the Washington Bureau to brief Phelps, the news editor.

“Bob,” I remember beginning. “This is incredible.” And for the next half-hour—like a jumping bean, unable to contain myself—I told him everything Gray had just told me. Pacing the length of the small room, I tape-recorded our session, and I gave Phelps the tape so he would have the details his notes might have missed.

I left the Times on August 17, 1972. For the next few months at Yale Law School, I read the Times every day, and I was certain I would see the story. It didn’t appear. I assumed the paper hadn’t been able to confirm it, even though I’d given them Segretti’s name.

Then, beginning in October 1972, I watched as the Washington Post began drubbing the Times. New York called me: Come back. I said no, but offered to make a phone call. I called Gray. He did not call me back.

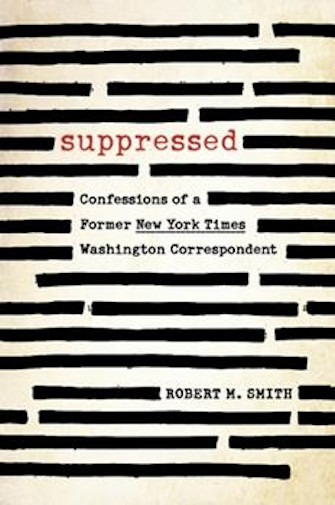

This is an excerpt from the new book, Suppressed: Confessions of a Former New York Times Washington Correspondent (Lyons Press) by Robert M. Smith. It’s published here with permission.

Highbrow Magazine

Image Sources:

--Lyons Press

--Dom Dada (Flickr, Creative Commons)

--PublicDomainVectors (Creative Commons)

-Maxpixel.net (Creative Commons)