Is Botero the World’s Most Famous Living Artist?

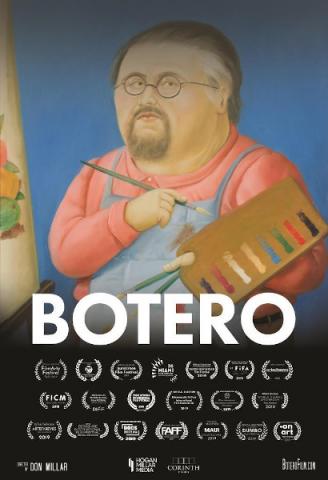

Botero

Directed by Don Millar

A Corinth Films Production

Fernando Botero may just be the most famous living artist in the world. It’s a pretty good guess, that no matter where you experienced your first Botero painting or sculpture—New York, Bogota, Paris, Madrid, Shanghai—you never forgot it. Chances are, whether it was a woman, a cat, a bird, even a Pope, it was, let’s face it, fat.

Those same artworks are also so much more—explosive, monumental, satirical, controversial, humorous, and wildly popular. In Don Millar’s engaging and heartfelt documentary of the artist, we are not only treated to a series of international exhibitions, a rich and constantly varied pictorial archive of the artist’s family and other personages of the art world, but a deeply personal portrayal of the man himself.

Born in Medellin, Colombia, in 1932, he lost his father at the tender age of 4, and his seamstress mother kept Botero and his brothers together by a thin thread. A natural aptitude for drawing emerged early and by the age of 16, he had sold a batch of his bullfighting sketches. Madrid, Paris, and Florence were waiting to be discovered. He didn’t want to be a better painter than his local Medellin neighbors; he wanted to be the best painter in the world.

Director Millar gives us insights into the artist’s processes, particularly through the reminiscences of his daughter Lina Botero Zea, who was also an executive producer on the film. At one point, she and a brother visit a storage space for their father’s works not visited since the 1960s. The viewer shares their excitement as they roll out the sketches, reveling in Botero’s strokes of color and endless experimentation.

His inimitable “Boterismo” style informs every subject, the style itself a mystery to the artist himself. In Botero’s words, “An artist is attracted to certain kinds of form without knowing why. You adopt a position intuitively; only later do you attempt to rationalize or even judge it.”

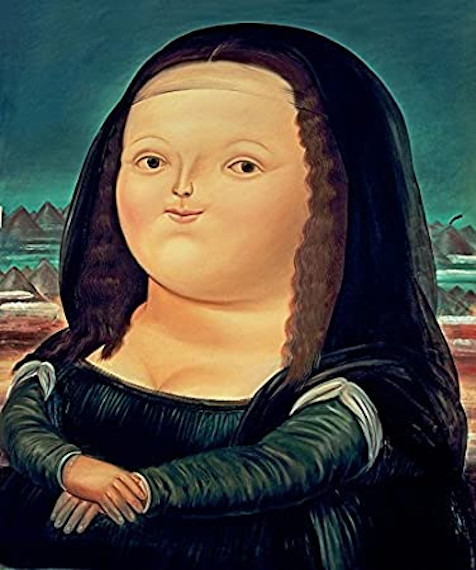

Volume and strength are twin passions of the artist, and the film provides generous glimpses in such paintings as Mona Lisa, Age 12, only one of many recreations of that iconic subject. Botero has an obvious interest in transforming historical artworks in his own style, an insistence he shares with his idol, Picasso.

The monumentality of his work is never better exemplified than in his sculptures. In one sequence, a signature piece is flown to its exhibition by helicopter. We are given the diatribe of one critic, who obviously resented a massive work dominating her beloved Park Avenue. During a visit to the Museo Botero in Bogota several years ago, I was stopped in my tracks by the largest single orange I have ever witnessed. The painting seemed to glow from its resident wall, overshadowing every other artwork or living presence. (It is worth noting that in 2000, the museum received 208 art pieces from the artist, 123 of his own making and the rest from his own collection of Chagalls, Picassos, and favorite Impressionists.)

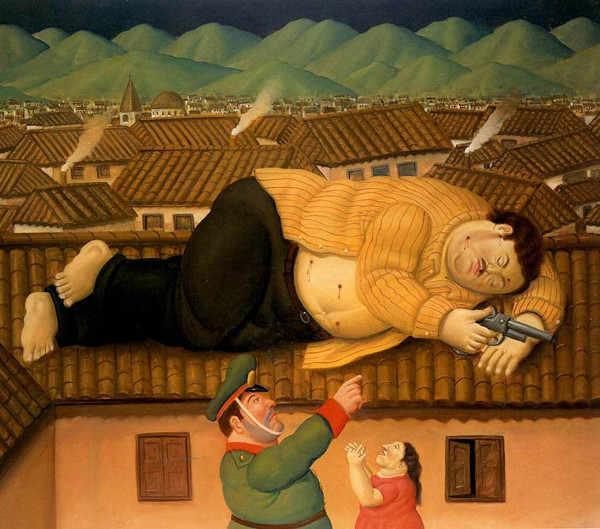

Death of Pablo Escobar is symbolic of the intimate role the artist has played in his home country’s affairs. Botero was troubled by the terrible violence from drug cartels, and this painting of the dictator’s demise is just one example of his attempt to describe it. When a bomb severely damaged his public sculpture of a dove, he wanted it left in place, constructing another to rest alongside it. In 2004, he began work on a powerful series of works evoking the horrors of Abu Ghraib, a grim testament to the U.S handling of prisoners during the Iraq war.

Throughout the film, we are introduced to a lighter side of the artist. My favorite was an early account of his mischievous nature. At one point, he served his children “eye soup”, a concoction of tomato soup topped off with a crystal eye from one of his sculptures. Describing his process of creating a work, he thinks “a smile is perfect,” demonstrating how he added a parrot to his subject. Such improvisation along the way in a work’s creation is part of what explains his global popularity. His appeal is universal.

A loving touch is everywhere evident in the film. Editor Henry Stein, who also co-wrote the documentary with director Don Millar, has managed to weave an enormous amount of material together without losing a beat. Even if you’re not a convert to Botero’s style, to experience such an account of one of the world’s most intriguing and individualistic artists is an almost guilty pleasure.

Author Bio:

Sandra Bertrand is Highbrow Magazine’s chief art critic.

For Highbrow Magazine