Life in France During the Age of the Coronavirus

Like other coronavirus lockdowns, France's happened in slow motion. First, the museums closed. Then about two weeks later, they shuttered the cafés and restaurants. And a week after that, authorities blocked access to the beach.

Today, Nice looks like it's in a dystopian science fiction movie. The streets of this resort town on the French Riviera are virtually empty. There are police checkpoints around every corner and an 8 p.m. curfew.

Across Europe, cities like Nice have all but closed in an effort to contain the coronavirus. Their experiences offer a sobering preview of what may happen in the United States as the virus continues to spread.

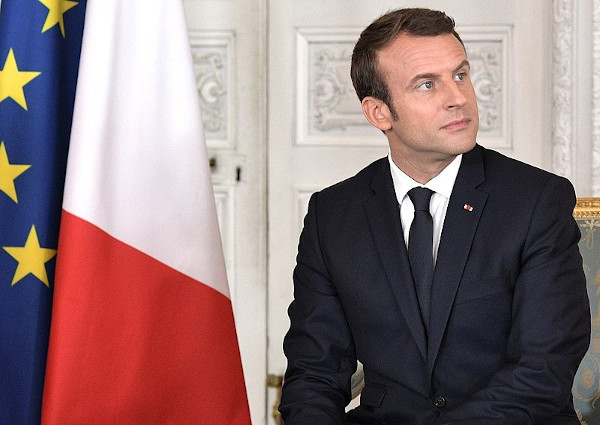

French President Emmanuel Macron put his country under lockdown effort on March 16 the same day President Trump first asked Americans to practice social distancing for 15 days (he has since extended those measures through April 30).

France is roughly two weeks ahead of the U.S. in the fight against the virus. What happens here could happen to America next.

Why we stayed in France despite the threat of a coronavirus lockdown

I've lived in Europe since January with my three teenagers. This was supposed to be our last trip together before my oldest son leaves for college. We spent a month in Lisbon and Porto and one memorable weekend on the island of Madeira and were headed to Italy in March. Then in late February, Italy turned into a red zone – and we detoured to France.

Nice is known for its Mediterranean climate and warm hospitality, and when we arrived early this month, we found plenty of both. We quickly connected with a group of friendly expatriates who promised to show us the Côte d'Azur and teach us a word or two in French.

Within a few days, stores closed and the streets drained of people. The U.S. embassy in Paris sent me an urgent email advising me to leave while I still could. But returning to the States would have taken several days, almost certainly exposing us to the virus. And if we'd gone back home to Arizona, we would have come into contact with relatives in the high-risk age group.

My kids and I are also curious, and we saw an opportunity to witness history. Nice hasn't had a curfew like this since World War II. Regular police checkpoints haven't been seen here in years, perhaps not since the 1940s.

Military patrol the streets of Nice, France, during the coronavirus lockdown.

Police checkpoints and fines

The first few days of the French coronavirus lockdown were tolerable. Essential businesses stayed open, which included not only supermarkets but wine shops, cheese stores and bakeries. (It is France, after all.) When shopkeepers heard us speaking English, they offered a faint smile. "You're from America?" they enquired. "And you're still here?"

Yes, still here. France is taking coronavirus seriously, and we feel safe in Nice, I told them.

But then the rules of the lockdown became more restrictive. On March 17, French authorities forbade residents from leaving their homes unless they were going to a job that couldn't be done from home, buying groceries, going to the doctor or pharmacy or exercising alone. If you're outside, you have to carry a signed affidavit that says you're out of your home for a valid reason or face a fine of $40 to $150.

Then the mayor of Nice, Christian Estrosi, tested positive for coronavirus. The next day, police stopped me while I was trying to walk along the Promenade des Anglais, the thoroughfare along the Mediterranean. Go home, they ordered. Shortly after that, they barricaded the crosswalks leading to the promenade, leaving the beach deserted.

A turn for the worse

During the next week, as the lockdown tightened, the mood of the city darkened. Even when I left home for a valid reason, and with all of the right paperwork, I looked over my shoulder. Was my reason for being out valid enough? Would the police fine me this time?

As I walked to the bakery, a man shouted from an apartment window, "Rentrez à la maison! (Go back home!)"

While I was in the boulangerie, I asked an employee how she's holding up.

"C'est catastrophique," she said. No need to translate that one.

There are long lines out the door at the grocery store. The two-meter social distancing requirement makes them look even longer. Most of the shoppers stare ahead in silence, their expressions concealed by face masks. But their eyes convey a single emotion: fear. They are afraid of getting sick, afraid of what comes next.

My daily walk to the supermarket takes me past a pediatric hospital, where I see young patients infected with coronavirus being carried up to the door by their parents.

Some parts of Nice look completely abandoned. Only a few homeless people remain. On my way to the grocery store, one of them stumbled toward me, murmuring to himself in French too quick for me to understand. The next day, he was gone.

Early this morning, I watched medics carry my neighbor into a waiting ambulance. That's when it hit me; coronavirus is in this building.

People have described life under the lockdown as a waking nightmare. In Nice, I prefer a cinematic analogy. After all, Cannes, the site of the famous film festival, is only half an hour's drive down the Mediterranean coast. (Like a lot of other major events, Cannes, which had been scheduled for mid-May, is canceled.)

This is like watching a low-budget movie about the end of the world, except that it never ends.

What happens after the coronavirus lockdown?

There are pockets of resistance, if not to the coronavirus, then to French authorities with their many rules. In front of a restaurant that sells takeout falafel, I saw a group of young men arguing in Arabic, sans social distancing. In Masséna Square, one or two residents stubbornly sat on park benches, enjoying the spring weather.

Every evening at 8 p.m., residents open their apartment windows and break into applause. They're clapping for the healthcare workers heroically putting their lives on the line to fight coronavirus. But they're also clapping for each other, applauding themselves for surviving another day in captivity. The pizza restaurant across the street stays open after 8 and drivers continue to deliver food to hungry residents. It turns out you can't impose a curfew on pizza delivery in France. The people wouldn't stand for it.

Maybe there's a reason why police seem to tolerate these small gestures of defiance. They're signs of a shared hope that the coronavirus will be contained and that the lockdown will end soon.

When people are released from their homes and the stores reopen, it wouldn't surprise me to see a celebration that will rival any this city has ever seen. And who knows, that day might fall on May 8, when Europe celebrates the end of World War II. In France, it's called La Fête de la Victoire (Festival of Victory). There may be no better way to describe the end of this long lockdown.

Author Bio:

Christopher Elliott's latest book is How To Be The World’s Smartest Traveler (National Geographic). This column originally appeared in USA Today. Republished with permission.

© 2020 Christopher Elliott.

Highbrow Magazine

Image Sources:

--Courtesy of Christopher Elliot

--Wikimedia.org (Creative Commons)