The Power of Brands, Conscious and Unconscious

Imagine yourself in your local supermarket, doing your usual grocery run. In aisle after aisle, countless brands vie for your dollars and attention. Colgate, Crest and Aquafresh toothpaste. Smucker’s, Welch’s and Dickinson’s strawberry jam. Coke, Pepsi and RC Cola soft drinks.

Like most consumers, you probably prefer one over another in dozens of categories that are collectively called consumer packaged goods. This class of goods includes things with a relatively short life cycle such as food, drinks, cosmetics and cleaning products. These items are used and replaced quickly, compared with durable goods like appliances and cars. True product innovations in this realm are rare, and actual distinctions between brands are typically slim. Yet reaching for your go-tos is almost automatic, and economists have long tried to determine why.

It’s especially curious because, as research has repeatedly shown, consumers in blind taste tests routinely fail to pick out their preferred brands. And they will happily purchase name-brand products such as Advil even when identical generic products sit right next to them on the shelf for a fraction of the cost.

People’s brand preferences are deep-seated and long-lasting. It’s not as simple as one brand being most popular across the board, though. Different brands dominate market shares in different geographic regions. In some cases, these market shares have generally been considered to remain stable over remarkably long periods of time, including those of Coca-Cola, Wrigley chewing gum and Gillette razors. Among food and beverage brands, nearly 50 percent of those that were dominant in the US in 1923 were still among the top five in 1997.

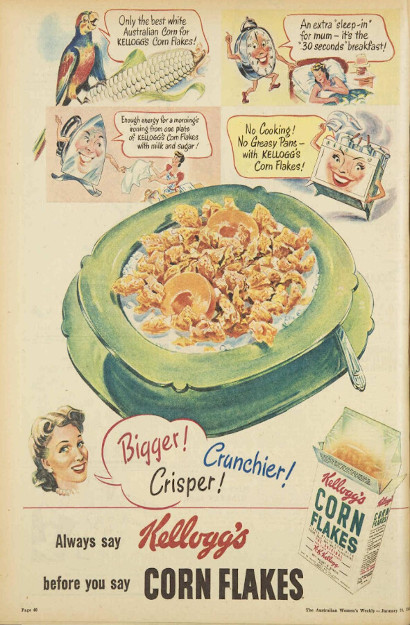

What’s in a brand? Brands are a relatively recent innovation, emerging in the early twentieth century. Over time, their value has shifted from a product-focused statement of origin to something that is valued in and of its self.

Precisely why people form lasting brand attachments to more or less indistinguishable products is a challenging question, says Stanford marketing professor Bart Bronnenberg. Psychology, geography, childhood experiences and advertising all exert some influences, concluded a 2017 paper in the Annual Review of Economics by Bronnenberg and Jean-Pierre Dubé, a marketing professor at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. But, they note, finding definitive answers is made harder by the fact that long-term, multi-decade purchasing data for individuals and households are difficult or impossible to obtain.

“We’re just scratching the surface here,” Bronnenberg says. “I think the exact mechanism through which this stickiness comes about is still unknown, but people are researching it, and we have several good answers.”

And while researchers have gained insight into how brand loyalties are formed and persist in the brick-and-mortar marketplace, the shopping landscape is changing rapidly. How consumer buying habits may change — and brand loyalties along with them — in the age of online shopping may pose even trickier questions.

Here are some of the best explanations researchers have for why you reach again and again for Crest, Smucker’s or Tide. And how those habits may change as shopping gets smarter and more connected.

“Consuming” the brand

Brands were originally used as symbols of quality. They communicated to consumers that this cow was raised by a reputable farmer, that this beer was brewed with untainted water, or that this loaf of bread was free from sawdust and other fillers.

“A century ago, as branding was really emerging, pundits tended to think of the brand as a means to identify the supplier of a commodity,” Dubé says. “But we have subsequently learned that consumers derive other benefits from the brand.”

In a classic study conducted in 1964, hundreds of participants were asked to rate different kinds of beer. With labels on the beers, the participants rated their go-to brand higher than the others. But when the brews were unlabeled, participants showed no preference. In other words, the brand alone made the beer seem to taste better. “It’s as if the brand is a complement to the product itself,” Bronnenberg says. “It adds value, or adds to the enjoyment.”

Many people think they can tell the difference between Coke and Pepsi, or Budweiser and Miller, but studies show that most can’t distinguish similar products when labels are hidden. A classic 1964 study showed this effect with beers.

This added value can extend from psychological effects to physiological ones, too. For instance, in a 2013 study, the antihistamine Claritin proved more effective at relieving symptoms in participants who took the drug and were then shown a Claritin advertisement, versus those who took Claritin and were shown a Zyrtec commercial. Here, Dubé says, is evidence that “buying the brand makes me ‘feel better.’ I literally consume the brand itself.”

The “cognitive miser”

In other cases, brand selection may merely be a matter of convenience. When you’re in the grocery store searching for all of the items on your shopping list, the kids are begging for lollipops and you’re trying to plan dinner ideas for the upcoming week, how much mental bandwidth do you have to spare?

People are, as psychologists say, “cognitive misers.” We tend to think and solve problems in the simplest possible ways. To help make choices, we form heuristics, or mental shortcuts.

“In the grocery store, you're making choices for sometimes 40 or 50 categories, each of which have like 40 or 50 alternatives,” Bronnenberg says. “It’s impossible to do this in a timely fashion unless you have these shortcuts like brands.” When it comes to choosing toilet paper or bottled water, the quickest way to make a decision might simply be to buy the brand you recognize, or the one you purchased last time. Here, Dubé says, the brand acts as a beacon, steering you toward things you’ve bought before.

And one snap decision may well turn into a behavioral pattern. As long as the product doesn’t let you down, that’s probably enough to earn your loyalty. Or, more accurately, you can’t be bothered to not be loyal. “You tried a brand and it worked,” Dubé says. “Why waste time finding something else?”

Home is where the brand is

Another possibility, raised in a 2009 study by Bronnenberg, Dubé and Sanjay Dhar, is that brand preference can stem from where you live. The team studied which brands dominate market shares in different regions, tracing each brand’s city of origin and the timing of its entry into other markets.

Bronnenberg and colleagues found that the dominant brand in a given region often reflects which brand hit the shelves there first, even if that occurred more than a century ago. In fact, a brand’s market share in its city of origin is approximately 20 percent higher than in a city 2,500 miles away.

And while this advantage erodes with distance from the city of origin, it does so only gradually. For example, Portlanders prefer Folgers coffee, first sold just down the coast in San Francisco in 1872, while Clevelanders prefer Maxwell House, which launched in nearby Nashville in 1892. This pattern held true across dozens of different categories of consumer packaged goods, from ketchup and mustard to bagels and breakfast sausages.

Geography, and familiarity, affect brand loyalty. Folgers, a product of San Francisco that initially expanded in the West and Midwest, tends to have larger market shares in those cities where the brand hit stores first. Maxwell House, which originated in Nashville, does better in eastern cities where it has a longer history.

But what about someone who moves from a Maxwell House town to a Folgers town? A follow-up study in 2012, by Bronnenberg, Dubé and Matthew Gentzkow, revealed how brand preferences evolve when people migrate. That work also explored the “stickiness” of these preferences throughout a consumer’s lifetime.

“Moving from LA to New York, for instance, creates a shock on your shopping environment, on your media environment, on what gets a lot of shelf space and what gets a little shelf space,” Bronnenberg says. “And so you quickly change some of your preferences.” About 60 percent of participants’ preferences quickly shifted toward items more popular in their new home. But the other 40 percent of preferences remained consistent with participants’ cities or states of origin, even for people who had moved decades ago. And while that 40 percent erodes over time, Bronnenberg says, it does so “very, very slowly.”

The particular preferences people stand by tend to be very idiosyncratic, Bronnenberg notes. “It’s not that all consumers stick with their coffee preferences but migrate their preferences for sugar or pasta sauce,” he says. “I think it’s that you have some favorite things that you yourself find important, and you stick with those preferences, and others you don’t.” A certain kind of pancake mix may be nearer and dearer to your heart than, say, the kind of syrup you squirt on top of it.

All in the family

That people can hold onto their original brand preferences for decades illustrates the importance of branding, Bronnenberg says. “If these effects are so sticky, if you could get people to buy your brand early on in their life, that turns out to be quite valuable.”

There is evidence that some brand preferences may develop in early childhood and last into adulthood.

First encounters can influence people’s thinking about entire categories of goods — so that, for instance, all facial tissue is thought of as Kleenex — and create long-lasting loyalties. The peanut butter brand you ate as a child, for example, may be your preferred brand into adulthood. This gives brands an incentive to advertise to children.

“If you get consumers who haven't consumed yet, their preference is like a blank canvas,” Bronnenberg says. “As a child, the first thing you got exposed to when you didn’t know any of the brands was this brand, and that occupies your mind space about this category.” Did you grow up in a house where Tide was always next to the washing machine, and not Gain? Were your PB&Js made with Welch’s jam and never Smucker’s? If so, you might simply come to associate the whole category — laundry detergent or jam — with the brand you encountered first.

The preferences of parents, too, often have an outsize impact on the preferences of their children, even later in life. One study found a strong correlation between the brand of cars purchased by parents and those purchased by their adult children. While cars are very different than breakfast cereals, this evidence suggests that brand preferences can be inherited, or at least trickle down the family tree.

Author Bio:

Ian Chipman is a writer who explores academic research on topics ranging from political economics and consumer behavior to space exploration and clean-energy policy.

This is an excerpt from an article by Ian Chipman that originally appeared in Knowable Magazine on Feb. 2019. Knowable Magazine is an independent journalistic endeavor from Annual Reviews, a nonprofit publisher dedicated to synthesizing and integrating knowledge for the progress of science and the benefit of society. Sign up for Knowable Magazine’s newsletter. Read the rest of the article here.

© 2019 Annual Reviews Inc.

Highbrow Magazine

Image Sources:

Kco0uvb (Pixabay – Creative Commons):

Matthew Paul Argall (Flickr – Creative Commons)

Alden Jewell (Flickr – Creative Commons)

Ichigo121212 (Pixabay – Creative Commons)