Costumes, Crackpots and the Occult: The Best British TV Imports

It will be interesting to see what media analysts years from now make of television in the 2010s. The small screen has been so dominated by lush period pieces (The Tudors, The Borgias, Mad Men), procedurals driven by brilliant social misfits (House, Dexter, Bones), and supernatural dramas (The Vampire Diaries, The Walking Dead, True Blood), one wonders at the odd mix of nostalgia, monster mania and obsession with mad genius that lurks in Americans’ collective unconscious. For British programmers, these are very familiar waters (Doctor Who alone pretty much spans all three genres), and US viewers are finding some UK offerings to be just their cup of tea.

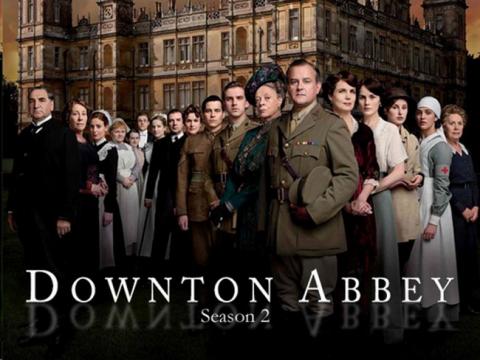

Lifestyles of the Rich and Edwardian: Downton Abbey

Leading the juggernaut in this latest British Invasion is, of course, Downton Abbey. The multi-award winning series follows the lives, loves and (mis)adventures of the aristocratic Crawley family and their staff at a fictional Yorkshire country estate starting in 1912 (Season Two opens in 1916, shortly after the onset of World War I). Classes are still sharply divided, but the sands of the status quo are beginning to shift. This tension between Edwardian and Modern England is fertile enough ground for scriptwriting, and costume dramas have plenty to offer visually, but in fact it is the show’s powerful melodrama and wonderfully drawn characters that have hooked American audiences.

Maggie Smith is reason enough to put Downton Abbey in the Netflix queue: the indomitable Dame adds a satisfying bite to a show swathed in noblesse oblige. Her Violet Crawley, Countess Dowager of Grantham, is unapologetically snobbish, entitled and calculating, with a propensity for wrapping sharp barbs in a velvet muff—in short, an old-school aristocrat. If you liked her in Gosford Park (and who didn’t?), you will love her here.

Her son, Robert Crawley, Earl of Grantham (Hugh Bonneville) and his American-born wife, Lady Cora (Elizabeth McGovern), oversee Downton Abbey. Together they paint a convincing portrait of those to the manor born. The elder Crawley daughters—lovely, arrogant Mary (Michelle Dockery) and plainer, envious Edith (Laura Carmichael), are bitter rivals, ever sniping at each other and competing over suitors and favoritism. Youngest daughter Sybil (Jessica Brown-Findlay), with her humility and keen interest in politics, is a first glimpse of the changing social mores on the horizon.

The series’ main storyline concerns the complications of finding Mary a suitable husband; as antiquated as the plot is, Dockery fills her role with such pathos and depth that one can’t help hoping this proud, cool beauty finds happiness…hopefully with Matthew Crawley, the middle-class distant cousin who finds himself heir to Downton. Dan Stevens plays Matthew clear-eyed, plain-spoken, and good-natured -- a refreshing contrast to the staid uprightness of the higher-born Crawleys.

Which takes care of the upstairs. Downstairs, the Downton Abbey residents “in service” are almost annoyingly cheerful, dutiful, and grateful to be attached to a fine estate…never mind the shared bedrooms, weekly half-days off and nightly locking of the door to the women’s quarters. With everyone so satisfied with their lot, social stratification has never seemed so appealing.

Thank heaven for the darkness that lurks in the heart of a few malcontents. Cruel, scheming footman Thomas (Rob James-Collier) specializes in framing and blackmail, which is not pretty—but at least he has the pluck to work the system to gain an edge. O’Brien (the excellent Siobhan Finneran), lady’s maid to the countess, is often his partner in crime, but tempers her cynicism and bitterness with a narrow streak of decency. These two are a constant nemesis to good Mr. Bates (Brendan Coyle), the valet with the bum knee and mysterious past. Why they waste their talents for mischief on one whose demise gains them very little…it seems beneath them somehow. Nevertheless, Mr. Bates is possibly the most admirable character in the show, and his slow, quiet romance with housemaid Anna Smith (Joanne Froggatt) is touching.

Things are all status quo in Season One. They get more precarious in Season Two. With real problems, like the Great War and injured or impoverished soldiers returning from the front, everyone is starting to reflect on their lives. Some yearn for more, some feel adrift, and some (like Edith) start finding there are better uses for their time than vicious gossiping. Even the Lord and Lady feel the nip of change on their fine-soled heels.

It’s hard not to be seduced by Downton Abbey’s fox hunts, dinner parties and mouthwatering dresses. The plots—scandals, betrayals, convoluted inheritance laws—are merely the stuff of soap operas, but they are written with wit, style and emotion. Mostly, though, it is the excellent cast and intelligently conceived characters that raise the show above mere costume drama and caricature.

Modern Problems, Classic Solutions: Sherlock

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s ingenious detective is transported to the present in Sherlock. Created by Doctor Who writers Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss, this Sherlock Holmes is even more of a curmudgeon than the literary character. Benedict Cumberbatch’s Holmes is snide, arrogant, unconcerned with social niceties—he could be Dr. Gregory House’s English cousin. He refers to himself as a “high-functioning sociopath” (an incorrect analysis the real Holmes would surely never make). He’s also capable of taking in a tremendous amount of information from minor observations—a polished ring, hair on a pant leg—and rapidly deducing sweeping conclusions that for all their outlandishness are nonetheless correct. More than a century after the Victorian detective was first introduced to readers, his powers of deduction continue to thrill and amaze.

Then there’s Dr. John Watson, played with a nice balance of admiration, exasperation and unflappability by Martin Freeman. His Army doctor, recently returned from Afghanistan, is a foil for the genius detective: He dates, he worries, he tries to help Holmes understand why certain things simply aren’t done. Maintaining the tradition of Watson as Chronicler, he also writes about the detective’s adventures on his blog; its popularity helps provide paying clients. Modern twists interwoven with Doyle’s classic elements make Sherlock so much fun. Pacing, atmosphere and plots seem at once faithful to the original and completely appropriate in a contemporary setting.

Characters from the novels pepper the series, with some interesting updates of their own. Irene Adler (Lara Pulver) has become a dominatrix with scandalous ties (ahem) to Buckingham Palace. Andrew Scott’s Moriarty, all well-cut suits, chilling playfulness and dramatic affectations, fills the series with wicked glee. Co-creator Mark Gatiss is brilliant as Mycroft Holmes; he never loses his air of genuine concern, even when administering a verbal slapdown to his impish brother.

Smart, humorous, and always engaging, Sherlock remains true to the crime procedural while keeping it fresh with a touch of levity. There’s a real pleasure in seeing a show written and produced with such reverence for the subject, such joy in its creation. Viewers may groan at a sometimes overwrought script, but once the game’s afoot, they won’t want to stop playing along.

“Flotsam and Jetsam of the Dead”: Being Human

American supernatural dramas tend to lighten the horror by camping and sexing it up (see True Blood). Being Human plays it straight. That’s not to say there isn’t humor in this story of a vampire, a werewolf and a ghost sharing an apartment in Bristol. But the title of the show refers to the characters’ efforts to carve out an ordinary human existence under extraordinary circumstances, and they are sincere (if at times misguided) in that mission.

Annie the ghost (Lenora Crichlow), haunting the apartment since dying there a year before, calls the three of them “the flotsam and jetsam of the dead”—although technically, George the werewolf (Russell Tovey) is alive. He’s a nebbish sort, with glasses and mouse ears and a nasally voice which becomes a high-pitched whine when flustered. The contrast between his timid human persona and the big, bad wolf is no doubt intentional, but stops being funny after a while. Dark, sexy Mitchell (Aiden Turner), a soldier turned vampire in World War I, acts as a mentor to the others. He’s also trying to kick the blood-drinking habit. Sweet, funny Annie wants to know why she’s still hanging around post-mortem. She has a penchant for making tea.

Which is useful, turns out: No matter how desperate the scrapes, there’s always time for witty banter exchanged over a cuppa. Watching three 20-somethings exposit Friends-style on life, love and relationships is tedious at times, amusing at others, and occasionally insightful. There are also plenty of eye-rolling moments: unnecessary explanations, unwise opening of doors, complications that anyone with a lick of sense could have avoided. And way, way too much “you just don’t get it, do you?” But the bonds formed among these eerie outsiders is at the heart of the series, which suggests that the most important factor that makes us human is our need to connect with others. Being Human for all its faults does not lose sight of this premise.

Trying to achieve “normalcy” throws plenty of obstacles in the trio’s path—particularly for George, who has some misadventures looking for sanctuary on a full moon. Then there’s the secret society of vampires bent on world domination, a shadowy group of paranormal investigators, and mysterious forces from beyond who show a sinister interest in Annie. Mix in crazy ex-lovers, unearthly creatures who come to call, and some twisted romantic storylines, and you’ve got a combination juicy enough to appeal to those who want entertainment along with their philosophical rumination.

Season Four aired on BBC America at the end of February, with an almost entirely new cast (of the principals, only Crichlow has remained). It’s not yet clear if the dramatic change will sink or reinvigorate the series, but American audiences could do worse than sink their teeth into this UK cult hit.

Author Bio:

Nancy D. Lackey Shaffer is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.