‘Since Parkland’: Young Journalists Tell the Story of Their Generation

iGeneration Youth

(TNS)

NEW YORK — Even before writing for her high school newspaper, from the very young age of 10, Akoto Ofori-Atta knew she would be a journalist. When she grew up, she vowed to focus on stories that mattered.

"I think there are many pressing issues of our time, and gun violence is one of them,” said Ofori-Atta, who has lost loved ones to gun violence. “As a journalist, I was looking for a place where I could devote my time, and resources, and talents to an issue of grave importance — one that is consequential, one that we grapple with, and something that is just a fact of American life.”

That’s how Ofori-Atta ended up as managing editor at The Trace, America’s only single-issue newsroom focusing on the gun-violence epidemic.

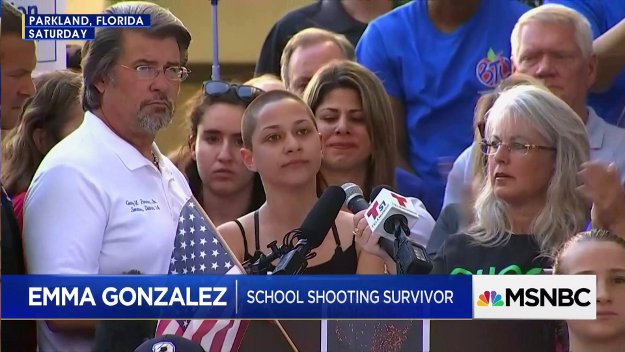

“Right after the Parkland shooting, we quickly realized that the gun debate in America had shifted to be one that focused on young people in this country,” she said. “We wanted to think about what that meant for our role as a newsroom that covers gun violence exclusively.”

Ofori-Atta had an idea for a story — a really big story: Get young people to tell the tales of the people their age who die tragically every year at the hand of a gun.

The Trace reached out to the right people: editors, designers, data researchers, funders, potential media partners, and journalism educators, who in turn recruited lots and lots of students. Together, they wrote bios for more than 1,100 young people who had been shot and killed since the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School last Valentine’s Day. That’s how “Since Parkland” was born.

Days before launching the website sinceparkland.org, the team behind the groundbreaking project shared with us some of what they consider the most important journalism lessons learned while reporting on the epidemic that's plaguing America’s kids.

Look at the Facts

According to Education Week, which kept count of the number of school shootings in which people were injured or killed on a K-12 school property, a school bus or vehicle, 24 shootings killed 28 students in 2018.

While working on the “Since Parkland” project, Mary Claire Molloy, 18, a high school journalist from Indianapolis, learned that mass school shootings are just “one small sliver of the American gun violence crisis.

“It gets the most attention when someone goes into a school and shoots kids, as it should, but there are kids everywhere in American cities dying every day — whether from murders, accidents, domestic violence, murder-suicides, or drive-by shootings.”

Molloy wrote 46 stories for the project. The incidents that affected her the most concerned Shelby Louise Hunn, 13, and Harrison Fredric Hunn, 15, siblings who lived in Zionsville, just one city away from her.

Molloy went to school one day to find her schoolmates who knew the teens somber and sad. On Sept. 21, 2018, Shelby and Harrisons’ father had shot them in their sleep before turning the gun on himself.

“There are kids everywhere in American cities dying every day that we don’t hear about,” said Molloy. “It’s part of a bigger picture of violence that we should be having a national conversation about.”

Start Early

Senior Project Editor and The Trace Curriculum Designer Beatrice Motamedi is a high school journalism teacher in Oakland, Calif. She worked with 150 students.

She saw lightbulbs turn on during the project, especially for high school students who didn’t already identify as student journalists.

“I think what happens is that they suddenly realized that citizenship doesn’t have a date. Journalism does not have a date. Citizenship and the First Amendment do not start at age 18,” Motamedi said. “They realized there are some very powerful tools out there that they can use to practice journalism and bring stories to light."

Learn New Formats

Before Motamedi was a journalism teacher, she was a working journalist. Even earlier, she was a poet. That’s why she suggested the 100-word and much smaller six-word stories that teens used to turn what could have been grim obituaries into tiny, loving portraits.

“The language of a story is very important,” said Motamedi, citing rhythm, cadence, and sentence variety as important components when trying to tell the story quickly in a short format. “Although some students struggled at first, eventually they learned it doesn’t take a lot of words to tell a story very well.”

Look for Visual Cues

One challenge students faced was writing stories about victims for whom there wasn’t much information. Allie Kelly, 18, who lives in Denver, applied the same strategies she uses as a student who is a visual learner.

When she found a photo on Facebook, Instagram or in a news report, she used the visual information it revealed. What color were their eyes? What was the shape of their smile? What was their style?

Kelly described writing one of the first stories she wrote, about a girl named Lauren Emily Kaufman: In the photos, Kaufman has silver earrings that frame her face. Her whole outfit was kind of eccentric. She had a wooden necklace, and a baseball shirt, but it was all very neat. “In that way, I was a little window into her personality,” said Kelly. “I tried to draw on that.”

Challenge Yourself

Motamedi said she finds her high school journalism students to be “exceptionally mature.” She said: “They’re empathetic. They have huge hearts. They’re often doing journalism in addition to a hugely packed schedule. There’s no one who has less free time in their day than a high school junior or senior. It’s always been a joy to be in a student newsroom.

“The secret I’ve had in my heart for 15 years is that high school students are entirely capable of the most ambitious projects in journalism. What I saw when this project started taking wing was that those things were coming true,” Motamedi said.

The Trace made some students, including Allie Kelly and Joe Myerson, assistant editors. “Suddenly, they became charged and responsible for teams of high school students and for the insane amount of recordkeeping and spreadsheet work and the daily demands of story production that all of us had.”

Myerson was happily surprised that their adult mentors actually meant it when they promised them equality. “At least for my team, 17-year-olds at the time — Allie and I — did a lion’s share of the editing. We worked alongside professional journalists, not below them. That goes for all the writers, too,” he said.

Kelly, current editor-in-chief of the East High Spotlight news magazine, led a group of sophomores and juniors in her home town. For many, it was their first journalism project.

“They took a chance on a crazy project because their editor in chief told them they should try,” said Kelly. “It is a really important work for teens by teens that couldn’t be told in any other way.

Write What You Know

“In the same way that we don’t think about the significant airport security after 9/11 any time we go travel to visit our grandparents, there isn’t any other story like this that overshadows our lives when we walk down the street or sit in our classrooms,” said Kelly. “It’s always in the back of our minds. I think that it’s incredibly important that this story was carried out by youth, by high schoolers.”

Be Aware of Biases in Media Coverage

“I learned that there’s racial disparity in coverage about gun violence victims. If I was researching a white victim, I would find so much more information, so many pictures and tributes. But if it’s a black victim, sometimes they’re nameless.” said Molloy.

Senior Project Editor Katina Paron, a New York editor who has worked with youth journalists for 25 years, said the project gave students a crash course in media literacy, a quick study in understanding how race affects media coverage on gun violence issues.

“They’re seeing a lot of stories about white kids in the suburbs who get shot, but no stories about black boys in Baltimore, black boys in Chicago who get shot,” Paron said. “So that’s one thing that’s opening their eyes to what’s already missing and how they can remedy that.”

Looking After Yourself

A large number of stories Sokhna Fall wrote involved people who took the lives of their own family members. In the most horrific one, a father killed three children, aged 9 months, 2 and 4, leaving one survivor, a 5-year-old. Fall said she will never forget them.

“It was difficult to write these pieces, considering how traumatic they are. At times, I found myself very emotional and on the verge of tears," said Fall, 17, who lives in Queens, N.Y. “Taking a break from working on these stressful stories and meditating using the Calm app helped me find a sense of inner peace."

Fall hopes the project will help humanize victims of gun violence. “We tend to refer to a lot of these events in statistics instead of actual stories,” she said. “I hope people understand that these events happen to real people.”

Have a Purpose

What held the teen reporters together through late-night Skype calls and stressful editing sessions was the care they felt for their peers.

The "Since Parkland" project "is not activism,” said Kelly. “It’s our attempt to have a voice in an issue that impacts our fellow American teens and our fellow American children walking to school, or going to the grocery store, or riding in a car.

“When people read this project, I want them to feel. I think it’s so easy to walk away, turn away, or shut your laptop; these stories are so incredibly devastating. I want you to cry. I’ve cried. That’s part of the goal,” she said.

Be Confident

“Since Parkland” educates on the issue of gun violence in America. An additional takeaway many students reported was the way the project validated them as journalists.

“Student journalists can be limited by the word ‘student,’ thinking we aren’t able to access police reports, or do investigative work, or cover really hard stories beyond classroom scuffles. I am a journalist. The Trace, the Miami Herald and my wonderful editors built my confidence in that,” said Kelly. “I am a journalist. And I’m a storyteller. And I’m capable of telling stories that are important and need to be told.”

Author Bio:

Cali Dickerson is an iGeneration Youth reporter living in Delmar, N.Y. She also contributed to the “Since Parkland” project.

Follow iGeneration Youth @igyglobal on Twitter.

Highbrow Magazine