The Best Books of 2018

Many notable books have appeared on recent “Best of 2018” lists, and some of these are included in my shortlist below. Other unjustly overlooked works of fiction and nonfiction appear here as well.

Notes from the Fog: Stories by Ben Marcus (Knopf)

Bad things happen, or are always about to happen, in Notes from the Fog, a luminous collection of short fiction by Ben Marcus. Whether it's a nice-guy dad driven to near-insanity by his weirdly precocious son, or a man who delights in staying behind in the aftermath of a devastating flood, Marcus unveils his characters’ inner lives with wit and dexterity, saying what often is left unsaid. Sentences spill out without a bump, both delicately constructed and piercing to the bone. And he’s a master of throwaway lines that tell entire stories in and of themselves:

“Because without a religion one must have a code. Without a code it’s like piloting a body with no bones through life, which some people do, god help them. Dragging a heap of skin from room to room, hoping people see you as a human being when you are only a spill. You’ve leaked from something larger that is gone now, not even a shadow, and you are all that remains. In the end it is too exhausting to approximate a real person.”

I dare readers to start the opening story, “Cold Little Bird,” and not feel compelled to explore more of this author’s work. These are bleak, dystopic stories, to be sure, but make no mistake—they’re also very funny.

Warlight By Michael Ondaatje (Knopf)

At the outset of Warlight, the young narrator, Nathaniel, and his sister Rachel, are abandoned by their mysterious parents and “left in the care of two men who may have been criminals.” What follows is a novel that encompasses coming of age, falling in love, and acts of espionage and petty crime against the backdrop of London after the end of World War II.

From this unlikely but compelling premise, Ondaatje spins a yarn that includes art theft, night-time sojourns on the Thames, adventures in greyhound smuggling and more, all rendered in lyrical and eerily precise prose: “I knew nothing about boats, but I immediately loved the landless smells, the oil on the water, brine, fumes sputtering out of the stern, and I came to love the thousand and one sounds of the river around us, that let us be silent as if in a suddenly thoughtful universe within this rushing river.”

If for some readers Warlight loses its way in the later pages, nonetheless the first third of the novel is as seductively written as anything the author of The English Patient has created before—an extraordinarily high standard to beat.

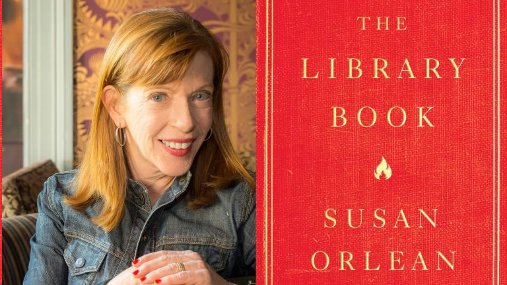

The Library Book by Susan Orlean (Simon & Schuster)

Susan Orlean’s paean to public libraries uses as its starting point the catastrophic Los Angeles Central Library fire in April 1986. Her description of the inferno is breathtaking, but only the start of a far-ranging blend of biography, true crime and absorbing first-person journalism. Orlean’s magpie approach to her subject isn’t surprising, once you buy into the notion that a book about libraries is a book about, well, everything.

Early on, she recalls coming back to her hometown library decades after leaving the city: “Nothing had changed—there was the same soft tsk-tsk-tsk of pencil on paper, and the muffled murmuring from patrons at the tables in the center of the room, and the creak and groan of book carts, and the occasional papery clunk of a book dropped on a desk.” No one can write a sentence like this without an abiding, lifelong love of books and literature. This is a deeply affectionate look at “the bigger puzzle the library is always seeking to assemble—the looping, unending story of who we are.”

Country Dark by Chris Offutt (Grove)

Set in rural Kentucky and spanning three decades, Country Dark is a lean, moody thriller about a Korean war veteran and the family he fights to protect. Tucker isn’t a particularly likeable protagonist—in fact, he commits the worst of all sins in a misguided attempt to save his loved ones—but over the course of the novel, Chris Offutt makes us care deeply about him and others in the hardscrabble country they inhabit in the 1950s and 1960s. His laconic prose style perfectly matches Tucker’s outlook on life and the memories he carries with him every day:

“He’d grown up with guns as common as shovels, but had felt a genuine affection for the M1 carbine. As the shortest and youngest member of his platoon, he rarely spoke. His first words were in response to a corporal asking how he liked his rifle. Tucker had said, ‘Shoots good,’ and a silence fell over the other men as sudden as a net. They looked at one another, then began laughing in an uproarious manner. Four died in combat and would never laugh at him again.”

Ninety-Nine Glimpses of Princess Margaret by Craig Brown (FSG)

Too bad more biographies aren’t like this one, a kaleidoscopic and irreverent look at the life of a now-deceased member of the 20th century British family, a princess determined to go her own way. Craig Brown dispenses with traditional linear narrative (birth, youth, middle age, old age, and death), preferring to draw us in with a series of impressions, anecdotes and speculations about Her Royal Highness (99 in all) that grow out of documented fact and salacious rumors.

Despite HRH’s life of bad behavior, Brown’s affection for her shines through. To be a British royal is its own peculiar curse, nowhere described as tenderly and humorously as in this charming, idiosyncratic biography.

Lee Polevoi, Highbrow Magazine’s chief book critic, recently completed a new novel, The Confessions of Gabriel Ash.

For Highbrow Magazine