The Art of Modigliani – The Man Behind the Mask

Upon entering the current exhibition, ”Modigliani UnMasked” at The Jewish Museum in New York City, the visitor first encounters a large black and white blowup from 1913 of Dr. Paul Alexandre, one of Amadeo Modigliani’s closest friends. Along with other workers, he is removing a tower of belongings from 7 Rue du Delta. Within this forced evacuation before the building’s demolition, two paintings of Modigliani’s, a co-resident, are visible in the lower foreground of the photograph—Head of a Woman and Melancholy Nude. It’s a sad image. Impossible, perhaps, not to be reminded of the mutability of life itself and the fragility of the work that remains of that life.

The next image seems to defy the specter of mortality. One sees a dashing, dark-haired man in a seated, relaxed pose. It’s a consummate photographic portrait that manages to be confrontationally masculine yet seductive.

Who was this elusive figure?

On display are approximately 150 works, those from the Paul Alexandre collection along with a selection of the artist’s paintings, sculptures and other drawings, as well as a number of key representative multicultural examples from African, Greek, Egyptian and Khmer cultures that serve as a counterpoint to his art.

As the wall notes indicate, Alexandre implored his friend “not to destroy a single sketchbook or a single study.” We should be indebted to this collector, as the largely black crayon sketches on view here are a master lesson in what line can do, how the curves and angles can surprise and delight. Alexandre managed to amass over 400 drawings from 1906 to 1914 when the artist was developing what would become his idiosyncratic style.

Several depictions of the Commedia dell’Arte character Columbine, the love interest of both Harlequin and Pierrot, are on view. Caught in mid-performance, the artist’s quick brushstrokes capture the figure’s balletic movement across the stage. A revelatory self-portrait of the artist as Pierrot, a surprising inclusion, would later appear as a painting. Even though Modigliani’s contemporaries were often taken with theatrical characters that were part of the bohemian world in which they coexisted, for him they were intimately connected with his own self-identity as the “Other” in Parisian society.

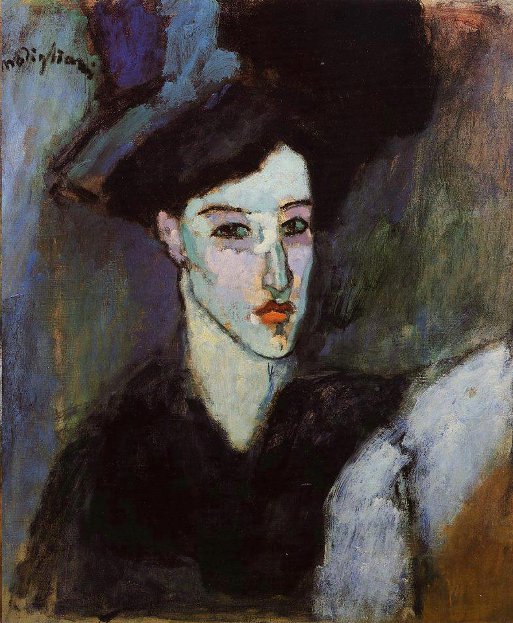

The Jewess from 1908 is a powerful example of his need to celebrate the subject’s Jewishness as he saw it. Based on his early lover, Maud Abrantes, the pale skin and the deep saturation of blues and greens grab the onlooker’s attention, but it is the aquiline nose that dominates the portrait. To illustrate the extent of antisemitism in the culture in which the artist operated, one has only to study the cover of La Libre Parole (The Free Word) on display. It features a Jewish man as physically grotesque, celebrating no doubt the pseudoscience of phrenology to suggest such facial qualities are biologically determined.

Born in Livorno, Italy in 1884 to a middle-class Jewish merchant family, Modigliani was well aware with his Italian good looks and fluency with the French language that he could easily pass as a gentile. But that was hardly his intent. “Je m’appelle Modigliani, Je suis Juif.” (I am Modigliani, a Jew) became his personal mantra when making introductions.

Conversely, concealment played a role for the artist. His fascination with cosmetics in his portraiture in such works as Portrait of a Woman with a Beauty Spot or Nude with a Hat, with the almost androgynous distortion of features, shines through. There’s an unmistakable desire in almost all his works to mask any signs of naturalism of his subject. A close kinship can be made in Nude to the exaggerated poses of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, a German Expressionist of note.

Actress in a Long Dress, with Bare Breasts demonstrates another early move away from naturalism, with the use of a blank eye in the subject’s expression. As for Modigliani the man in this artificial construct, he would often mask his long history of tubercular onsets behind drink and drugs. It was better to be inebriated in public than to give in to the defeat of a serious malady.

There are several portraits on display of his closest ally, Alexandre. The sketches are deft and sensitive, such as Paul Alexandre with Left Hand in His Pocket. But the most intriguing depiction of his friend is Unfinished Portrait. The face and background are flattened and more abstract in treatment than the rest, almost as if Modigliani wanted to obliterate any likeness to the man.

One of the most telling exhibit quotes by the artist is as follows: “Always speak out and keep forging ahead. The man who cannot find a new person within himself is not a man.” For Modigliani, the decisive move toward metaphorical abstraction was absolute. One senses in the later paintings and sculpture a no-turning-back sensibility; he was ready to toss his hat in with the gods of the ancients. French colonialism was making West African sculptures and other ritualistic objects available for study back home and Picasso and Matisse took note. In Modigliani’s case, the exposure created a sea-change in the artist.

A mask from the Fang-Nturu peoples of Equatorial Guiana is prominently placed in one of the first rooms. As a referential object, it appears right at home. Other artifacts are judiciously encountered while strolling through the maze of work and manage not to deter from Modigliani’s own sizable sculpture offerings.

Alexandre’s family provided some of his first commissions, but the portrait was no longer a way of depicting a strictly identifiable self for Modigliani. The equestrian Baroness Marguerite de Hasse de Villers is a case in point. Several studies, entitled “The Amazon” were made and in the finished portrait he decided to change the color of her riding jacket from red to yellow. That was the final straw for the baroness but Alexandre was only too happy to purchase the painting of his brother’s paramour instead.

Perhaps the most provocative of Modigliani’s love interests, not only because of her own historical place in Russian literature but because of the drawings and sculptures she inspired is the poet Anna Akhmatova. For the artist, she was the perfect embodiment of the statuesque, patrician Egyptian queens he found in his visits to the Louvre.

In 1911, though married at the time, the poet returned to Paris for several weeks to be with him. The results speak for themselves. These life studies, seated, reclining, nude, or lying on her stomach indicated through a sureness and economy of line that he had found his quintessential model. Head, from 1911-12 is placed in the center of the room, and is one of the finest limestone sculptures on display. The triangular shape of the head and the bangs are attributed to her, and the inscription attests to the contours of the Egyptian ankh (an anagram for Akhmatova). Passion and inspiration obviously went hand in hand in this relationship. She also figured prominently as a kneeling caryatid. Caryatids, statuesque figures from antiquity upholding architectural weights, held a special fascination for him in his drawings.

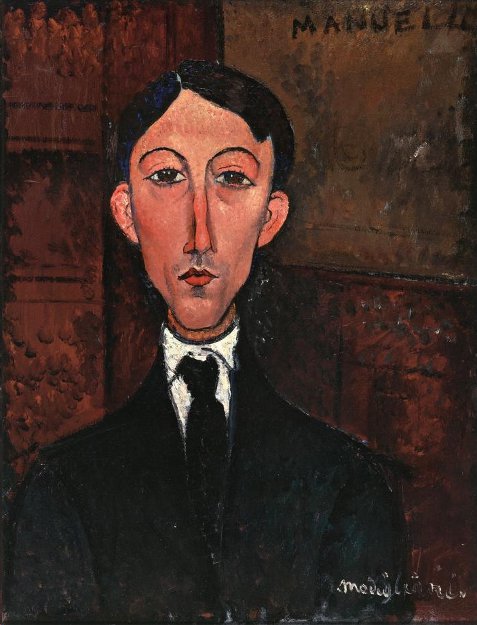

Many portraits, such as the one of Spanish painter Manuel Humbert Esteve, show that the artist did not completely eschew all the particularities of the subject’s identity. To his contemporaries, the pursed mouth and parted hair make clear who the sitter was. Once Modigliani’s style was firmly entrenched, such individual marks could shine through.

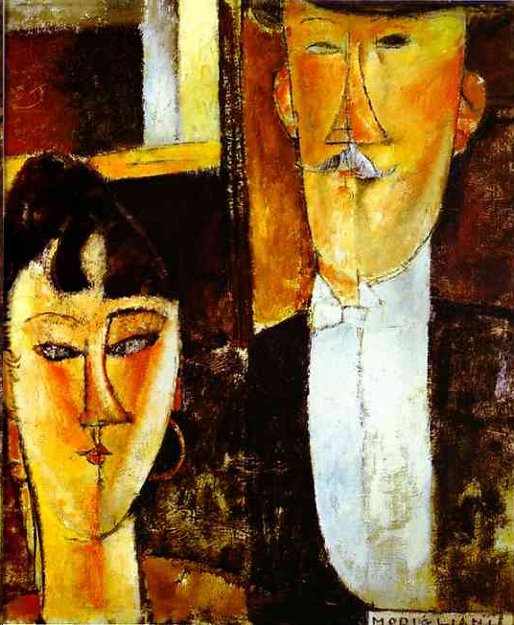

Another key figure to enter the artist’s life in the winter of 1916-17 was Jeanne Hebuterne, a young 19-year-old art student who soon became his lover and then wife. The portrait on view shows her in a yellow sweater, the elongated masklike face and body showing no traces of eroticism. It was Jeanne who gave Modigliani a baby girl the following year, also named Jeanne. Soon pregnant again, she would suffer the loss of her husband to tubercular meningitis on January 24, 1920. Grief-stricken, she threw herself and her unborn baby from the fifth-floor window of her parents’ home the following day.

Modigliani’s surviving daughter Jeanne became a tireless advocate of her father’s legacy and is the author of his biography, Modigliani: Man and Myth.

Modigliani’s portraits continue to fascinate the viewer, as mysterious and strangely modern in execution today as they were upon their creation. We may never know all the reasons that inspired their singular genius but one thing is certain: They show that the truth of an individual life perceived lies far beneath a natural likeness.

Modigliani Unmasked will run through February 4, 2018 at The Jewish Museum, 1109 Fifth Avenue at 92nd Street, New York, NY 10128.

Author Bio:

Sandra Bertrand is Highbrow Magazine’s chief arts critic.

For Highbrow Magazine