A Look Back at Walter Mitty

Perhaps one of the benefits of a culture ravenously looking backward for old things to make new again is the occasional adaptation of an old story into a movie. While adaptation itself is, like translation, is an art form, it's not always easy to evaluate. Should we sacrifice artistic license on the altar of fidelity? It's no secret that there's no easy answer to this and other questions of artistic value in adaptations.

While some might see this as a bad thing, it has helped to put more art in front of more eyes: Hamlet adaptations didn't end with Lawrence Olivier, and there's much to be said in favor of the adaptation starring Mel Gibson, even if the more mischievous viewer dwells on the question of whether it is not Mel Gibson who is mad as opposed to the Danish prince he's playing (how's that for meta?).

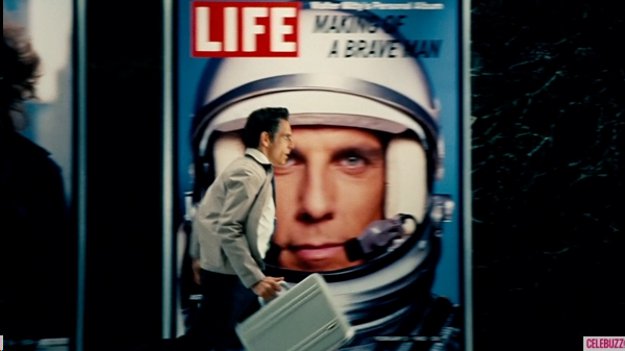

A recent adaptation which really took wings and flew with its subject matter is definitely Ben Stiller's The Secret Life of Walter Mitty. Based loosely on a 1939 story by the beloved New Yorker humorist, James Thurber, Stiller's adaptation starts out with large goals. Before we can discuss this adaptation, though, it's probably best to get a look at its subject.

While Thurber is generally considered a humorist, he has a bountiful capacity to write fiction of a darker mien. Stories like “The Lady on 142” and “The Catbird Seat” prove there's an edge to Thurber's mind. Walter Mitty is easily described as a henpecked husband who drifts into reveries to escape his wife. At first, it's easy to mistake the daydreams for flashbacks, but, on closer examination, they fall apart.

Why would a flight captain be in full dress uniform? For the more technically inclined, a 50.80 handgun is almost a cannon. And the closeness of the “Von Richtman circus” to Von Richtoffen's flying circus, which was definitely popularly known due to flying ace Eddie Rickenbacker's memoir Fighting the Flying Circus and other World War One pieces that immortalized the Red Baron, Manfred von Richtoffen. But, my favorite, are the nonsense medical terms: “obstreosis of the ductal tract,” “streptothricosis,” and “coreopsis” all sound as though they've succumbed to sepsis due to contamination of bovigenic fecal matter.

While Stiller's Mitty daydreams are well done, there is an issue. The Benjamin Button reverie is a little obvious, as is the train platform dream which appears to be Spider Man inspired. The Stretch Armstrong fight escalates quickly from action movie caliber violence to full-on cartoon absurdity. The difference between Thurber's approach and Stiller's is in subtlety. Thurber's Mitty is believable at a layman's first glance, but once the reader starts trying to substantiate details, the story falls apart; Stiller's, on the other hand, hits the viewer with a hefty dose of fiction quality material.

For Stiller's adaptation, this poses a problem when Mitty is traveling through Greenland and Iceland. The storyline and action scenes are the type one would expect to lump with Mitty's earlier dreams, and yet here they are, with no discernible means of separating them from the realities Mitty creates in his head from that outside of Mitty. While Thurber provides us with some kind of cue, one reasonably easy to see, a sign for the reader to be in on the joke, Stiller leaves the viewer close to helpless.

The general direction of the plots is also different. Thurber's Walter is trapped in a relationship — I hesitate to write it, but it appears a psychologically abusive relationship — that he uses his reveries, possibly subconsciously, to escape. Stiller's Mitty, on the other hand, through going out and doing things close to those he dreams about, seems to escape. This is illustrated by Stiller's Mitty being unable to locate slide 25, which captures the “quintessence of life,” until he has lived a life worth bragging about. It's almost an extended commercial for an adventure travel company.

The choice between the red and blue car at the rental car lot is worthy of mention, if only because it almost candidly pulls the idea from the red pill of The Matrix. Two jelly bean, or pill, shaped cars, red and blue; the only thing missing is Lawrence Fishburne working the counter. Gone is the smirking subtlety of Thurber; now arriving, a brick of all too easily accessible metaphor — think fast.

According to the Rotten Tomatoes “Critics Consensus,” “It doesn't lack for ambition, but The Secret Life of Walter Mitty fails to back up its grand designs with enough substance to anchor the spectacle.” While critics can often get caught up in the hate fest of critical takedowns, it appears this judgment has largely held true after reflection.

Author Bio:

Adam Gravano is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.

For Highbrow Magazine