When Did Democrats Become the Party of Elites?

This article first appeared on BillMoyers.com.

How did it come to pass that of the two political parties, the Democrats — who have long fought for the underdog, civil rights, consumer protections, universal healthcare, the minimum wage and for unions against powerful interests that try to crush them — have now been branded in large swaths of the country as the party of the establishment and the elites?

And how did it come to pass that Republicans — whose policies, regardless of stated intent, benefit polluters, entrenched interests and the upper brackets of American wealth — are now seen by many as the anti-establishment populist party which delights in flipping off elites on behalf of the Everyman?

For the moment, keep Donald Trump out of this conversation — after all, Democrats have been hemorrhaging seats in statehouses and Congress for decades. Also set aside any talking points about which party’s policies truly benefit forgotten Americans or which short-term trends show up in the polls.

More important for Democrats is whether they can rewrite the political narrative that now has them on the side of the establishment and Republicans on the side of sticking it to the man.

If Democrats want to regain their electoral stride and recapture defiant voters who once saw the party as their advocate and voice — the same voters they need to establish a sustained governing majority throughout the land — they must think less about policies per se than about how those policies translate to messaging and brand.

Just as consumers purchase products not merely for what they do but for what they say about the people who buy them, voters are drawn to narratives, brands and identities as much as the policies that affect their lives. These narratives give voters meaning, define who they are, and become an essential part of their identity and self-image.

And what’s most toxic in American politics today — as it has been throughout our history — is to become the party associated with domineering overlords and supercilious elites who seem to enjoy wielding power over the rest of us.

To some extent, the Democrats have only themselves to blame for their elite, establishment image.

Few question the party’s need to build its campaign coffers in what is now an arms race for political dollars. But by cozying up to Wall Street and the privileged — and appearing more at ease hobnobbing among them than among those who work in factories, small businesses and call centers — Democrats have sent a subtle message about the people they prefer to associate with and seek out for advice. To many Americans, it reeks of hypocrisy at best.

Republicans, who unapologetically celebrate wealth as a symbol of American dynamism, face no such messaging dissonance.

But perhaps more important is the jujitsu maneuver that Republicans have used to turn one of the Democratic Party’s strengths — its good faith use of government to level the playing field and help the little people — into a weakness.

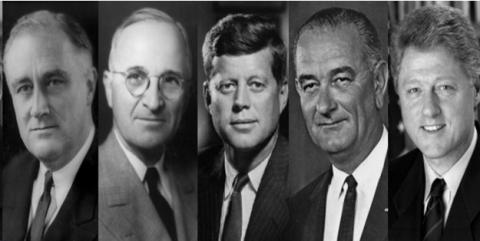

From the New Deal through the ’60s, the Democrats were able to show that government was an essential tool to correct market inequities, protect the little people from unchecked power and special interests and ensure that the American birthright included safeguards against crippling poverty and misfortune.

Government, most Americans believed, was their defender and their voice. In 1964, according the American National Election Studies, more than three-fourths of Americans said they trusted government most of the time or just about always. It was the Democrats who stood for grass-roots change and the Republicans who represented the powerful and resistant establishment.

Democrats then expanded their vision of a righteous government by exercising its power to fight segregation, discrimination, environmental blight, corporate malfeasance and consumer hazards — and to advance healthcare as a right and not a privilege. All of that seemed to follow the New Deal script of government as a force for good.

But with Richard Nixon channeling George Wallace’s racialized anger at the federal government and Ronald Reagan saying that the only way to christen our shining city on a hill is to free up aggrieved entrepreneurs and ordinary citizens stifled by burdensome red tape and regulations, the Democratic association with government began to turn noxious.

As Reagan put it in his 1981 inaugural address, we should not allow “government by an elite group” to “ride on our back.”

For four decades now, Republicans have succeeded in framing Democrats as the party that uses government to bigfoot rather than aid the American people. Democrats may celebrate public servants for keeping our food safe and our lakes healthy, but Republicans have successfully portrayed them as humorless bureaucrats who salivate at the urge to exert power and control over taxpaying Americans.

And Republicans have very artfully created a counternarrative, turning the market into a synonym for liberty and defining it as an authentic expression of American grass-roots energy in which small businesses and entrepreneurs simply need freedom from government to shower benefits on us all.

Of course the market’s magic may be more mythical than real — given that powerful corporations and interests dominate and exploit it often at the expense of workers — but that inconvenient fact is immaterial to the brilliant messaging advantages Republicans have derived from it.

Indeed, in the Republican playbook it’s the teachers, unions, environmental groups, professors and civil rights organizations that constitute the establishment whereas Koch and other industry-funded astroturf groups are the real gladiators fighting the status quo.

But it’s not just the Democratic association with government that Republicans have used to brand it as the party of the establishment and elites. Republicans have also turned the table on the liberal values that Democrats embrace.

Beginning in the 1960s, liberals have sought to flush prejudice, bigotry and discriminatory attitudes from society by turning diversity into a moral value and creating a public culture intolerant of misogyny and intolerance. On the surface, that should be a sign of national progress.

But conservatives — with help from an unwitting or overly zealous slice of the left that too often overreaches — took these healthy normative changes and cleverly depicted them as an attempt by condescending and high-handed elites to police our language and impose a politically correct finger-pointing culture.

In effect, conservatives have rather successfully portrayed liberals and Democrats as willing to use cultural and political power against ordinary Americans. They want to take my guns, regulate my business, dictate who I can hire, and tell me what I can buy, which doctors I see, how I live, when I pray and even what I say — so goes the conservative narrative.

That their definition of “ordinary Americans” is quite narrow — meaning whites and particularly men — is beside the point because it’s the political branding that matters, not the fact that liberal economic policies and efforts against bigotry and discrimination have helped millions of ordinary Americans.

Taken together, Republicans have successfully defined Democrats as a party of bureaucrats, power brokers, media elites, special interests and snobs who have created a client state for those they favor, aim to control what everyone else does and look down their noses at the people who pay the taxes to fund the same government that Democrats use to control their lives.

And why is this so damning for Democrats? Because our nation was founded on resistance to power, and it’s part of our political and cultural DNA to resent anyone who exercises or lords that power over others.

Read past the first paragraphs of our Declaration of Independence and it’s all about King George III and his abuses of power. Our Constitution encodes checks and balances and a separation of powers. Our economic system rests on antitrust law, which is designed to keep monopolies from crushing smaller competitors and accumulating too much power.

So if large numbers of Americans see Democrats as the party of entrenched elites who exert power over the little people, then Democrats have lost the messaging battle that ultimately determines who prevails and who doesn’t in our elections.

And let’s be clear: Donald Trump didn’t originate this message in his 2016 campaign; he simply exploited, amplified and exemplified it better than almost any Republican since Ronald Reagan.

The Bernie Sanders answer, of course, is to train the party’s fire at banks, corporations and moneyed interests. After all, they are the ones exerting unchecked power, soaking up the nation’s wealth and distributing it to the investor class and not the rest of us.

And to some extent that has potential and appeal.

But remember, most Americans depend on corporations for their jobs, livelihoods, healthcare, mortgages and economic security. So it’s much more difficult today to frame big business as the elite and powerful establishment than it was when workers manned the union ramparts against monopoly power. Working Americans today have a far more ambivalent relationship with corporate America than they did in the New Deal days.

Somehow Democrats have to come up with their own jujitsu maneuver to once again show that theirs is the party that fights entrenched power on behalf of the little people. Liberals have to figure out how to merge their diversity voice with the larger imperative of representing all of America’s underdogs. These are not mutually exclusive messages.

Democrats can preach all they want on healthcare and Trump and the environment. But if they don’t correct the larger narrative about who holds power in America — and who’s fighting to equalize that power on behalf of us all — then whatever small and intermittent victories they earn may still leave them short in the larger battle for the hearts and souls of American voters.

This article first appeared on BillMoyers.com.

Author Bio:

A former speechwriter and strategist for causes, candidates, and members of Congress, Leonard Steinhorn has written two books on American politics and culture and frequently writes for major print and online publications. He is currently a professor of communication at American University and a CBS News political analyst.