The Factory Factor: Andy Warhol and the Velvet Underground

The long-range impact that the Velvet Underground had on the rock world may best be summed up by an oft-repeated quote from Brian Eno: “The first Velvet Underground album only sold 10,000 copies, but everyone who bought it formed a band.” Undervalued in their time, still revolutionary-sounding to modern ears, their first album, 1967’s The Velvet Underground & Nico, surely stands as one of rock’s most influential records of all time.

And yet, it could have easily been an album that never was. The Velvets’ harsh cacophony of sound – drones, dissonance, feedback, and distortion – was a far cry from the peace-and-love movements sweeping most of the musical cultures and countercultures during that famous Summer of Love. Their lyrics explored the dark sides of urban life: drug use, S&M, paranoia, prostitution, homosexuality, and general sleaze. As far as crafting commercial pop hits was concerned, principal songwriters Lou Reed and John Cale – along with Sterling Morrison on guitar and Moe Tucker on drums – were running on the opposite track and in the opposite direction. They deliberately and defiantly stood against everything rock was, or was purported to be, at that time.

In the days before independent labels or DIY recording, it’s a miracle the Velvet Underground were allowed to step foot inside a studio at all. But they were – and for that, we mostly have Andy Warhol to thank.

Shortly after they first started playing together, the Velvet Underground got a low-paying residency spot at a club whose patrons were less than enthusiastic about some of the group’s material. After one performance of “The Black Angel’s Death Song,” for example, they were told if they ever played it again they’d be fired on the spot. But for the group, that was part of the thrill. John Cale, a Welsh-born and classically-trained viola player, has described their sound and vision during this period: “We were really excited. We had this opportunity to do something revolutionary – to combine avant-garde and rock and roll, to do something symphonic. No matter how borderline destructive everything was, there was real excitement there for all of us. We just started playing and held it to the wall. I mean, we had a good time.”

Paul Morrissey, a close confidant and business manager for Andy Warhol, happened to catch one of their club sets in 1965 and sensed potential. Warhol’s fame in the art world was at critical and popular peak; he’d abandoned painting and had started to venture into experimental filmmaking and multimedia productions. He wanted a rock band for a new performance installment he had in mind, and with the Velvet Underground, he found them.

The result was the Exploding Plastic Inevitable, an intentionally assaulting and occasionally insulting show of strobe lights and whip dancers surrounding the Velvets’ musical performance, with Warhol’s films projected on-screen behind them. But Warhol did more than give the band a high-profile gig – or, within a few months of their working together, pay for their studio time. Though Cale and Reed had written many of the songs featured on The Velvet Underground & Nico before Warhol’s entrance, Andy introduced that latter element of the album’s title into the band itself: Nico, AKA Christa Paffgen, a German-born model and aspiring singer. As Morrissey has explained: “The group needed something beautiful to counteract the screeching ugliness they were trying to sell,” and with her tall, stately posture, her flaxen hair and sultry voice, Nico fit the bill.

More than introduce an attractive new member, the group’s access to Warhol’s inner circle – the “Factory,” as it was called – provided aesthetic and musical inspiration. “It was like heaven,” Reed said. “I watched Andy; I watched Andy watching everybody. I would hear people say the most astonishing things, the craziest things, the funniest things, the saddest things. I used to write it down.”

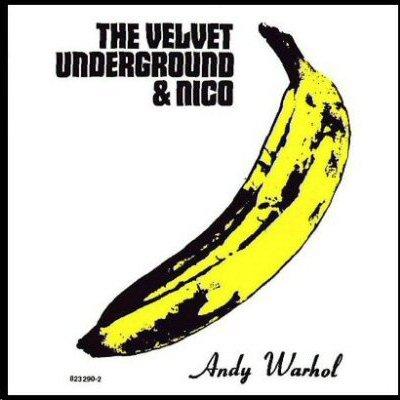

The relationship between Warhol and the Velvets seems obvious now, in retrospect; solidified in the popular imagination by that iconic peeling banana album cover. But what elements really brought the two together? What appeal did one have for the other? Who was influencing whom here? Warhol’s artistic “pop” sensibility seems antithetical to what the Velvets were trying to do – destroy pop. As rock critic Ellen Willis has described, the Velvet Underground was “too overtly intellectual, stylized, and distanced to be commercial;” their work was “anti-art made by anti-elite elitists.” The same might be said about Warhol’s most famous images: familiar objects like Campbell’s soup cans or Marilyn Monroe’s face made strange through repetition – made cold, somehow, and not like pop at all. “Andy and us were cut from somewhat the same cloth,” Reed said, “and we wanted to shake people up a little bit.”

What links the Velvet Underground with Andy Warhol is their common design to expose the structural elements of their genres. Warhol wanted to break down the highbrow world of art; the Velvets wanted to elevate the lowbrow world of rock. Warhol utilized the most crass of commercial goods to question the sanctity of the art-subject; the Velvets brought grit and urbanity into the naïve teenage daydreams of radio-rock. For both of them, as musicologist Simon Warner has put it, “Ugly was not the new beautiful, but it may have been… the new true.”

In their brief tenure together, the whole of which lasted less than two years, Warhol’s most important influence on the Velvet Underground may have been his ability to shield them from outside influence at all. In the studio for their first album, the band had initial difficulties working with producers or engineers who tried to mollify or commercialize their sound. Warhol didn’t know anything about music, but when he came into the sessions as “producer,” the dynamic quickly changed. “Andy was the producer and Andy was in fact behind the board gazing with rapt fascination… at all the blinking lights,” Reed explained much later. “He just made it possible for us to be ourselves and go right ahead with it because he was Andy Warhol. …We’d just walk in and set up and do what we always did and no one would stop it because Andy was the producer. Of course he didn’t know anything about record production – but he didn’t have to. He just sat there and said ‘Ooooh, that’s fantastic,’ and the engineer would say, ‘Oh yeah! Right! It is fantastic, isn’t it?’” In the end, “the record went out without anybody changing anything because Andy Warhol said it was okay. It’s hilarious. He made it so we could do anything we wanted.”

As both parties soon found out, however, managing and producing a rock band involves more than a wall of artistic protection. Financial mishandlings and managerial disputes caused The Velvet Underground & Nico’s release to be delayed for a full year after recording; when it finally hit shelves, it sold poorly, and Andy and the Velvets soon split ways. The long shadow of Warhol’s name – a name that featured prominently on the band’s album cover and spine, causing some confusion over who the actual players were – proved too much to overcome. “‘Produced by Andy Warhol,’” Reed once griped; “it was like being a soup can.” Still, without his help, it might have been a can that never got opened at all.

Author Bio:

Sandra Canosa is Highbrow Magazine’s chief music critic.

For Highbrow Magazine

Photo Credits: Wikipedia Commons (Creative Commons); Wikimedia Commons (Creative Commons)