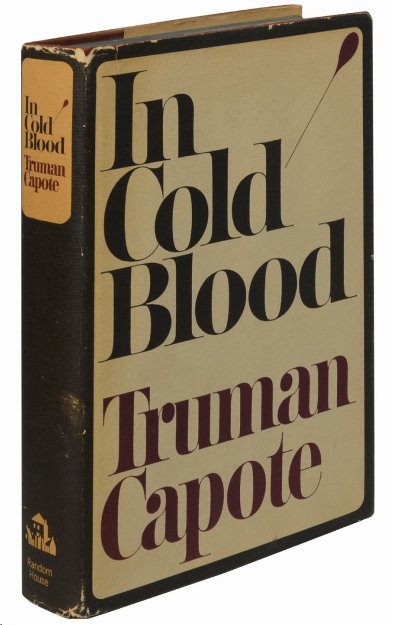

Truman Capote’s Tale of Murder: ‘In Cold Blood’ Fifty Years Later

The party is at Jean Stein`s in the spring of 1965. In a room full of literary and theatre people is British drama critic Ken Tynan, famous for ensuring the success of John Osborne`s Look Back in Anger, and Truman Capote, author of best-selling Breakfast at Tiffany`s. At the centre of the noise and gaiety, Capote, dressed immaculately as usual, is in especially high spirits. He has just heard that the final appeal has been lost - Smith and Hicock will be hanged for the murder of the Clutter family six years earlier. Tynan observes Capote jumping up and down with glee - `I`m besides myself! Besides myself! Besides myself with joy!`

Can this be right, he thinks - this celebration of two men`s forthcoming deaths, however terrible their crimes, just because it provides closure to the writer`s book. There is a quarrel but no reconciliation and a few months later Tynan writes his review of In Cold Blood, accusing Capote of a lack of moral responsibility - of failing to properly intervene in the legal process to save the accused from the rope. `No piece of prose, however deathless, is worth a human life.`

Almost from the moment of first publication in book form In Cold Blood - soon to be a best-seller and Book-of-the-Month Club selection - is surrounded by controversy. Has the author, by not doing enough to prevent the two culprits` executions, compounded the ruthless and chilling murders depicted in his book? After all, without them and their co-operation, there would be no book. In spite of Capote`s furious protests and in spite of such notable defenders of his cause as the notable cultural commentator, Diane Trilling, the phrase `in cold blood` begins to take on additional significance - to refer not only to the original killings portrayed, not only to the refusal of the Court to show mercy but also to the author`s own behavior.

If questions about the author`s relation to the ending of In Cold Blood provokes one set of moral issues, another set is suggested by the genre of the book. Determined to break out of the constraints of the conventional novel-form, Capote seeks to merge fiction and non-fiction - to record what had happened at Holcomb (an event he read about in a New York Times report) and its impact on the community by conducting a series of interviews with local residents and investigators. Relying on memory for 6,000 post-interview notes, using the novelist`s techniques of selection, scene arrangement, dramatic presentation and crafted language but at the same time claiming that his work `reflected ...the essence of reality`, Capote`s `nonfiction novel` unsurprisingly drew criticism from those concerned about the ethical implications of what he was doing.

In the same manner that such major American writers of the Sixties as Roth, Mailer and Vonnegut seek to grapple, in their different ways, with the problem of finding a form and language to convey the particular texture of the turbulent decade, Capote turns to the hybrid form of the nonfiction novel to capture the reality of the times. If there are a few inaccuracies or distortions, then this is the price that has to be paid for a work that does justice to a `truer truth.`

From the 1965 publication of In Cold Blood then, the line between fact and fiction and, arguably between truth and lies, becomes a lot less clear-cut.

Issues of moral responsibility are also involved in Capote`s choice and treatment of his subject matter. His decision to select one of the most brutal killings in American history as the centre of the book, after the light and delicate portrayal of upper-class New York society in Breakfast at Tiffany`s, is both brave and risky. Asking readers to watch and emotionally engage with the killing of a whole family in their home would obviously shock and horrify many. In Cold Blood is no detached report of a crime committed hundreds of miles away but rather the detailed and graphic representation of the invasion of a secure and affluent home by terrifying alien forces. Not only the Clutters are threatened and terrified but so also, at one remove, are all middle-class, Midwestern American families. In a society that is witnessing increasing violence, whether from political activism or social unrest, the implied and disturbing message of In Cold Blood is that no part of America is completely safe.

Capote`s depiction of some of the key participants in the crime - both victims and perpetrators - also has the potential to disturb. Whilst the Clutter family is depicted as eminently upstanding and respectable, we might wonder, as each member is briefly referenced in the book`s opening pages, as if in an inventory, whether there isn`t something a little cold and detached about the presentation?

Similarly, although husband and father, Herbert, is certainly a widely admired figure in the community -someone who looks after both his wife, who suffers from psychiatric problems, and his children, with admirable care, his self-assurance and dominance - he is referred to as `the master of River Valley Farm` and wants to break-up his daughter`s relationship with her steady boyfriend - do little to endear him to the reader. When Capote writes - `Always certain of what he wanted from the world, Mr Clutter had in large measure obtained it`, his style - the neatly balanced sentence, the use of the formal `Mr.` and the somewhat impersonal vocabulary seem to reinforce the idea that he lacks a certain amount of warmth. This lack, together with Herbert`s puritanical traits - `of course he did not drink` - and his caution - he has recently undergone a medical examination for a life- insurance policy - mean that we only occasionally - as when he is shown as a caring husband or a decent employer - sense his humanity.

Whilst Mr. Clutter may be shown limited sympathy - at least before his death - Perry Smith, one of his murderers, is shown a good deal. Capote, sent away as a child to live with distant relations after the break-up of his parents` marriage, seems emotionally drawn to Perry, whose dislocated and poverty-stricken life as the mixed-race child of itinerant circus-performers, speaks to his own insecure upbringing.

Instead of the distanced style used for Herbert, Capote renders the murderer`s thoughts and feelings from inside -`Still no sign of Dick. But he was sure to show up`. And throughout the narrative, in the references to his liking for adventure, to his playful experiments in front of the mirror and to his singing, there is a strong emphasis on the character`s inwardness and imagination. In spite of the terrible acts he commits, he possesses, unlike his partner, a sensitivity to others - he is careful, for example, not to cause the Clutters unnecessary pain before their deaths - and an intelligent self-awareness about the crimes he commits - `And just then it was like I was outside myself... It made me sick. I was just disgusted` - that subverts conventional responses.

Here again, In Cold Blood raises serious questions for the reader about the writer`s moral position. Shouldn`t our sympathies be focused on the victims of the crimes depicted rather than on their perpetrator - particularly as Capote describes the crimes in such dreadful, slow-motion, detail? The fact that the book prompts such concerns suggests its power to disrupt settled and taken-for-granted attitudes, reminding us that it is written and published at a time when a whole range of such attitudes - social and political as well as moral - are under attack.

The links between In Cold Blood and the wider shifting Sixties` culture is also apparent in the treatment of sexuality. Although heterosexual relationships are presented through the typically traditional adolescent courtship between Nancy Clutter and Bobby Rupp - a matter of dates and dances - and through Hicock`s crude and exploitative attitudes to girls and sex, Capote is also interested in something a bit more unconventional and subversive. There is the intense, if fraught, connection between the two murderers, there is Perry`s strong feelings towards the prison chaplain he encounters while serving time and there is the author`s own close bond with Perry, hinted at in the closing stages of the book but suggested by subsequent rumours and gossip. It is these male relationships that have an authenticity and intensity that are absent from the heterosexual relationships of the book.

Capote may have started his investigative project, with Harper Lee as his collaborator, as a literary experiment to record the impact of a crime on a community but he was increasingly affected by the emotional claims of the killers` lives. Never really on the wrong side of the law himself himself, his own identity as an openly gay celebrity means that he knows the meaning and implications of deviance from the inside - a knowledge that enables him to recognise the pain and fear of those on the margins of society - whether they be murderers or not.

By the end of In Cold Blood, readers have been asked to overlook the author`s own problematic relation to the fates of his characters, to ignore the traditional boundary between fact and fiction, to extend their sympathies towards the brutal killer of a whole family at the expense of his victims and to recognise that heterosexuality may be a less powerful force than homosexuality in Capote’s world. In addition, by questioning the capability of the US legal process to provide a fair trial for two young men whose lives have been stunted in different ways by the society in which they have grown up, Capote is also raising concerns about the morality of capital punishment.

If In Cold Blood is not be quite as directly critical of the system as some other 1960s` texts - for example, Catch 22 or One Flew Over the Cuckoo`s Nest - nevertheless it also belongs to that time, 50 years ago, when traditional certainties were coming under critical scrutiny and attack. Just as much as Heller or Kesey, Capote wants his readers to reflect on their preconceptions and to think and feel differently about the world around them.

Author Bio:

Mike Peters is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.