Can Music Survive Without the Teenybopper Fangirl?

It seems counterintuitive to call a Justin Bieber concert “Kafkaesque,” but that’s just the feeling I got walking around downtown Brooklyn when the boy wonder was scheduled to play Barclays Center last year. Throngs of preteen girls crushed the streets, the sidewalks, and the subways with imminent devotion in their eyes, shrill excitement in their squeals, with a very nearly propagandist smattering of Bieber’s cherubic face filling the fronts of T-shirts, homemade posters, and concert programs for blocks in every direction from the auditorium.

To an outsider, the gathering of Beliebers in such large proportions can be dizzying, if not downright menacing: strange words to ascribe mostly prepubescent girls in the awkward middle stages of growth spurts, hormonal changes, and corrective braces and eyewear. But the apparent strength of their allegiance to Justin – whose music and lyrics are mostly innocuous, if not downright dumb, to most grown adults or “serious” music fans – is what is most disorienting. The communal desires, the vast groupthink, and the worship of a (false?) idol smells of blind consumerism at best and fascism at worst.

Justin Bieber’s mindless, pandering puppy-love songs (and, more recently, his douchey antics and run-ins with the law) have made him an easy target for the butt of many jokes, especially within the music press. But is it really the music we all so love to hate, or is it the seemingly unflappable popularity of the man himself? Even after his DUI arrest in Miami Beach earlier this year, Twitter fan groups poured out a hashtag of love for the Biebs: “#wewillalwayssupportyoujustin”.

To say that the Belieber phenomenon is anything new or unusual would be a grave discredit to the generations of fangirls that have fueled popular music since the end of World War II. From Elvis to ‘N Sync and David Cassidy to New Kids on the Block, fervent fandom, especially from young girls intent to follow musical and fashion trends – “teenyboppers” – has been both encouraged by the music industry and largely disdained by the general public.

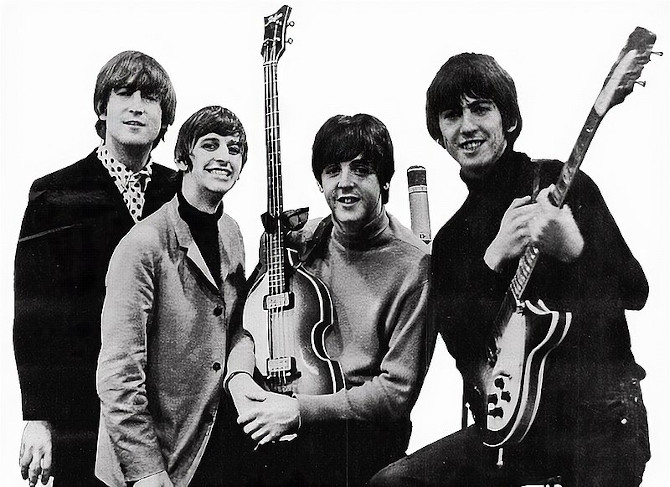

Nowhere was the fever pitch of teen pop star devotion more apparent, or maligned, than in the early stirrings of rock’n’roll with the mass hysterical outbreak of Beatlemania on both sides of the Atlantic. A 1964 piece from Britain’s New Statesman reads just as well about fans of the Fab Four then as it might apply to Directioners (fans of boyband One Direction) today: “While the music is performed, the cameras linger savagely over the faces of the audience,” future NS editor Paul Johnson wrote. “What a bottomless chasm of vacuity they reveal! The huge faces, bloated with cheap confectionery and smeared with chain-store makeup, the open, sagging mouths and glazed eyes, the broken stiletto heels: here is a generation enslaved by a commercial machine.”

There’s no questioning that the archetypal corporate executives in the music industry, the ones we imagine to be greedily counting their stacks of fortunes in high-rise corner offices like a well-groomed Scrooge McDuck, play a huge role in generating pop stars like One Direction, 5 Seconds of Summer, the Backstreet Boys, or the Monkees – perhaps the most direct precursor to modern boybands as one of the first completely industry-designed-and-fabricated groups. Acts like these are created precisely because, if the formula is right, they will sell, sell, sell – especially to that all-important demographic of 10-17 year old girls. Not just through album or single sales, not just through concert tickets, but especially through the commodity merchandise: posters, T-shirts, fanzines, documentary films, necklaces, headbands, perfumes (like the one called “Justin Bieber’s Girlfriend”). Anything put out with a heartthrob’s name attached, the girls – it is almost guaranteed – will gobble up.

This is what is disdained most about young fangirls: their apparent gullibility, their obsessive devotion, their compliance with the forces of consumerism – the “commercial machine” – that not only promotes conformity among the girls but aggressively sucks the pennies from their pockets. Teens and preteens, who are often granted disposable income for the first time through parental allowance or part-time jobs, feed their money directly into the already-obese wallets of the record company executives when they participate in the planned obsolescence of teenybopper trends. What’s hot one month is likely to be passé the next; staying cool and hip is a constant process of purchasing – which is exactly how the industry likes it.

But is this really the whole story? Are young girls merely unwittingly brainwashed by capitalism? Are they truly slaves to the corpocratic regime of “coolness”? Is this all there is to being a fangirl?

The most obvious and distinctive thing about fangirls is that they are, of course, girls. It is important that they are not boys. It may sound Eisenhowerian, but it still holds largely true that boys have more ways to become men than girls do to become women. Boys are offered a variety of expressions on the path to manhood: they can be athletes, brains, rockers, skaters, or any number of things. Girls, on the other hand, tend to have far fewer options. A girl is defined first by her sex: her path to womanhood hinges largely on her ability to become a girlfriend, wife, and eventually mother. Boys may define themselves, but girls are defined through their relationship to boys.

The teen boy idol is a safe, idealized space for girls to project their emerging fantasies of love. In many ways, this kind of daydream man-worship – as evidenced by the doodles in hearts of “Mrs. Bieber” scrawled across countless school notebooks – reinforces stereotypical gender norms. It encourages female subservience, heterosexuality, and dictates modes of desirable behavior to the girls themselves (like 1D’s “You don’t know you’re beautiful / But that’s what makes you beautiful”). On the surface, fangirldom is perhaps not the most revolutionary or empowering course of action for young women today.

But there are deeper levels at play. Fandom does not exist solely within a vacuum, especially in today’s Internet age. There are legions of sites, Facebook groups, and Twitter conversations that, while born out of fandom, often develop into meaningful bonding moments between girls. Belieber and Directioner forums combine threads of celebrity gossip with conversations about love, relationships, and understanding one’s own body in a communal space largely between and within other like-minded girls. By actively participating in an audience fan culture, teens can also find meaningful experiences outside the realm of the commercial machine.

Evident, again, is the way teen girl crowds gather at concerts. As much as the concert-going experience is about the love of the performer, it is also an opportunity for young girls to bond with each other in a public sphere, an all-too-rare occurrence in a society that prefers women to be confined to the home. Fandom allows girls an avenue through which to explore and discuss their emerging identities and attitudes with other girls, especially toward taboo (for girls) subjects such as sex and desire. There is a community-building aspect to fandom that has little to do with the politics of consumerism and everything to do with the politics of gender. In some ways, the commercial machine offers girls tools – however small – for resistance and change.

To what extent fangirls can or will use the master’s tools to dismantle the master’s house is debatable, perhaps even downright idealistic. But bonding over stars is simply the first step in bonding as humans. While the answers to self-actualization and empowerment might not be expressly found in the pages of the latest issue of Tiger Beat, the opportunities for interaction and communality between girls offers distinct spaces for the development and growth of the self, of what it means to transition from a girl to a woman. It is in these spaces that identities and meanings emerge, defined not by what the girls consume, but what they say and do with each other and for themselves.

Author Bio:

Sandra Canosa is Highbrow Magazine’s chief music critic.

Photo Credits: Depositphotos.com; Wikipedia.org (Creative Commons)