Mind Your Language: The Danger of Inaccurate Comparisons

Imagine this: It is October of 2010 and you and a few friends decide to take a weekend trip up to Montreal. You board the Amtrak train at Pennsylvania Station in New York City and take a trip north, admiring the reds, oranges and yellows of the changing foliage. You arrive in Montreal in the evening, check into your quaint bed and breakfast, and grab a quick bite, hoping that the earlier you get to sleep the sooner morning will come

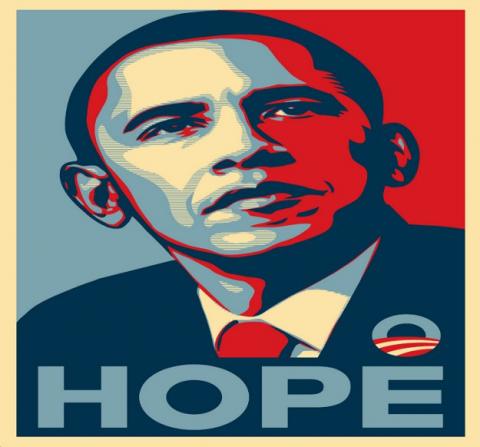

In the midst of Montreal’s cobblestone streets and colonial mansions is a small, wooden, fold-up table upon which sits the now iconic Shepard Fairey image of Barack Obama. It does not take long for you and your friends to realize there is something odd about this particular incarnation of the poster because there, just above President Barack Obama’s upper lip is a toothbrush mustache worn, most infamously, by Adolph Hitler. There you stand, all three of you American, two Jewish, staring blankly at an image of your president adorned with the facial hair of the orchestrator of arguably the largest genocide in recorded history. Of course, this could have happened anywhere that the Worldwide LaRouche Youth Movement is active considering its obsession with the Hitler/Obama mash-up. The image has turned up in New York City, Indiana, Virginia and beyond. Even still, the imagery is problematic and leaves a person wondering: Do these people even know what Hitler was responsible for? And to go one step further, does this misuse of images and, by extension, words take away from the real significance of them? Should the state have a role in controlling the trivialization of certain references?

One can only assume that those responsible for the distribution of this questionable image know exactly what Hitler is infamous for. They use this image as a way to stir up controversy, to prove a point. But what is the point, exactly? According to one LaRouchePac member named Ian Overton, “He has earned his mustache. It’s not a gas chamber but it’s an economic policy. It’s the same effect. If you’re dead, you’re dead.” The thing is that an economic policy does not have the same effect as the Holocaust. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum defines the Holocaust as “the systematic, state-sponsored persecution and murder of approximately six million Jews by the Nazi regime and its collaborators.” The Museum also remembers the millions of non-Jewish individuals who suffered and died under Nazi rule including, but not limited to, homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Poles, Roma and Sinti, persons with disabilities, Blacks, and Soviet prisoners of war. The Holocaust was a highly organized, highly centralized effort to rid the world of huge swaths of the population in order to create a “superior” Aryan race. It was, in fact, a genocide, a word coined by Raphael Lemkin in his study on the occupation of Europe by the Axis states.

This might seem an unnecessary history lesson but that is not the case. Images, and the words that oftentimes accompany them, have a tendency to take on lives of their own. The mustache sported so famously by Hitler represents many things. It represents fear, violence, extermination, destruction, hate. The very fact that someone would use an image as loaded as that of Hitler to make a statement about an economic policy is irresponsible. That being said, the policies born from economic theories have had huge impacts on the lives of millions upon millions of people. One need look no further than the former “banana republics” in Central America or the streets of American cities such as Detroit and New Orleans to see the results of economic policies gone wrong. Sadly, people have suffered and died as a result of such policies. But the purpose of the policies themselves was not to kill. That distinction, in this case, is important.

Although one can potentially make the argument that economic policies under recent American presidential administrations have inflicted adverse living conditions upon groups of people resulting in a perceived threat of physical destruction of that group, the purpose of the policy in and of itself was not to cause such harm. Are these policies immoral? Perhaps. But the real question is: Are they genocidal? The obvious answer is that they are not because they do not meet the criteria of genocide under accepted international legal norms.

Overton went even further than simply holding up the sign. He drew the comparison out further by making reference to gas chambers, one of the main methods of mass killing used during the Holocaust. As attention-grabbing as the comparison might be, a gas chamber and an economic policy are not the same thing. The creation of a transportation system designed solely to shuttle people to camps within which they were to be tortured, starved, gassed and worked to death is different from a set of economic policies that oftentimes have incredibly adverse effects on the people who are forced to live under them.

Ian Overton and the Worldwide LaRouche Youth Movement are not the only ones to make comparisons between President Barack Obama and Adolph Hitler. A Republican State Representative of Arizona, Brenda Barton, took to her Facebook page in October, 2013 and said “Someone is paying the National Park Service thugs overtime for their efforts to carry out the order of De Führer…” Try to ignore the obvious racial tones of this particular post. Although the literal translation of the word “führer” in German is leader, it is commonly associated with Adolph Hitler, a fact Rep. Barton was undoubtedly aware of when she made the comment. To invoke the reputation of Hitler when talking about the closing of national parks was callous and irresponsible. The irresponsible overuse of comparisons to Adolph Hitler, World War II and the Holocaust do not make a point more valid or effective, they simply have the effect of undermining the significance of the events themselves.

This was a point Israel tried to make when, this past January, members of the Parliament proposed a law banning non-educational use of the word Nazi, or any other slur or symbol associate with the Third Reich. The penalty for breaking this law was suggested as a fine of up to $29,000 and as many as six months in jail. The proposal was met with mixed reviews. The January 15, 2014 New York Times article on the subject quoted one of the backers of the law, Shimon Ohayon, as saying “We have to be the leader of this battle, of this struggle, in order to encourage other countries…We, in our land, can find enough words and expressions and idioms to express our opinions. What I’m asking is, please put away this special situation that has to do with our history.” On the other side of the debate are many people, including those with connections to the Holocaust, who say this is a clear infringement on the right to free speech and that enforcement of such a law would be simply impossible. A better approach, according to Avner Shalev, the director of the Holocaust museum and memorial Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, would be through an educational process and lively public debate which could help people realize the impacts of their use of such hurtful and loaded terms and images.

The idea of criminalizing certain allusions to Nazism, Holocaust denial, and the supposed promotion of genocide is not unheard of. Many countries, including Brazil and a handful in Europe, do not allow the use of Nazi symbols and flags. Taking it even further, Rwanda criminalizes anything the government believes to be akin to hate speech, which was one of the factors blamed for the Rwandan genocide of 1994 that resulted in the deaths of 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus within 100 days. Much like the proposed ban in Israel, this law makes sense in some ways. In the lead up to the Rwandan genocide, both public and private media outlets used violent language which, it has been argued by the United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), incited the 1994 genocide. As a result, the Rwandan government is leery of any language it thinks might cause the repetition of recent history but, according to the Amnesty International report “Safer to Stay Silent,” the ambiguity of the legislation has resulted in a fear of speaking out or criticizing authorities, which has led to what many consider to be a one-party state.

The difference here is that Israel, unlike Rwanda, is a democracy, meaning that the right to free speech is staunchly protected. And, unlike the European laws that work to outlaw anti-Semitism and neo-Nazism and the Rwandan laws that try to protect against more violence, the proposed Israeli legislation is to try and counteract the trivialization of terms associated with the Holocaust. People are understandably upset about the use by young people of the Hebrew word “shoah,” which means catastrophe but is normally used only to refer to the Holocaust, to describe common mishaps such as tripping on the sidewalk. The question still remains: Does the overuse of Holocaust imagery and comparisons take away from the meaning of the words? The answer, in short, is that much like our overuse of the word “war” it probably does. There is this idea that people should respect the sanctity of certain words because of their tie to specific events and that by cheapening the words you only succeed in cheapening the events themselves.

What members of the Israeli parliament are worried about is a similar erosion of the power of specific words and images that historically highlight persecution and death on a grand scale. The loss of this power could somehow make the experiences of those during the Holocaust, as well as the long history of persecution of Jewish people even in modern times, less meaningful to future generations. In terms of free speech and democracy it is likely not the smartest move, but a protection by the state of words that remind us all of the terrible results of the Nazi rise to power is understandable. It would be a shame if we let those terms and visuals lose their bite and significance.

Images and words are meaningful. No matter how much an individual dislikes Barack Obama, his policies, and his administration, there is really no grounds for a comparison between him and Hitler, or between his policies and gas chambers. Those comparisons do not strengthen a point, they undermine the pain and suffering of millions of people and the families they left behind. But perhaps those things need to be discussed and decided within the public sphere, rather than dictated by a state. As irresponsible as it is to soften the meaning of words and images associated with institutionalized violence, and as ill-advised it is to plaster a Hitler mustache on the face of the president of a democratic state, making it illegal seems like an invitation to stifle public participation and healthy debate.

Author Bio:

Rebekah Frank is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.