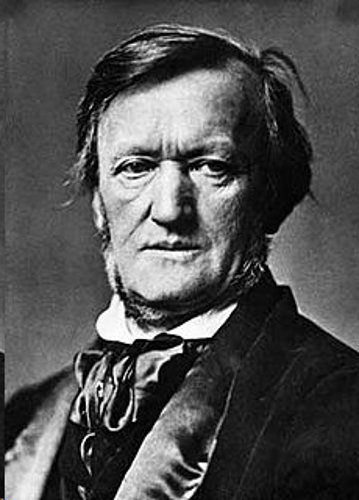

Reflecting on Controversial Composer Richard Wagner on His 200th Birthday

More people wrote about him than about any other person in history – with the exception of Jesus, Luther, Napoleon and Marx — they say. In 2013 the world is celebrating Richard Wagner’s birthday for the 200th time — his obit for the 130th.

Wagner’s work continues to cause great emotions, ranging from sheer enthusiasm to utmost rejection, and his recitals attract people to opera houses all over the world. The poet, director, conductor, writer and first and foremost composer, remains a mystery for many, and doesn’t cease to polarize even 130 years after his death. Some see in him the ingenious originator of the “Gesamtkunstwerk” (total work of art), while others discredit him because of his anti-Semitic writings. However, that he changed the face of opera remains unquestioned.

Despite all the controversy about his persona, one thing is certain: Wagner was a creator of greatn music and deemed himself the greatest. “Richard Wagner loved the superlative”, writes Christian Staas in DIE ZEIT Geschichte. “It had to be nothing less than the ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’, the ‘infinite melody’, the ‘music of the future’. [He] needed [his] own festival hall, and he didn’t just compose operas: in the end he created with Parsifal a ‘Bühnenweihfestspiel’ ("A Festival Play for the Consecration of the Stage"). Right from the beginning it was about more than just art for him.”

In life too, things couldn’t be exuberant enough. His many affairs, adulteries, and horrendous debts speak for themselves. “Whoever met him was startled by and surprised at how childishly he behaved; how ostentatiously and monomaniacal he entertained his company; how flagrantly he spoke of his role as a Messiah; how he wallowed in plush; how, with just a few chords on a piano, he engendered an unearthly poignancy; how he persuaded emperors and kings and behaved like an ill-bred child; how, in one moment, he could burst into crying fits and cut capers in another; how he unashamedly pestered the most noble-minded natures for money,” notes Wolfram Goertz in DIE ZEIT. His life was one big opera in itself.

He was born in the Jewish quarter of Leipzig on May 22nd 1813, “in a tenement that rubbed shoulders with the lodgings, shops and synagogues of the very people he was so catastrophically to anathematize” as the ninth child of Carl Friedrich Wagner, a munipical official and his wife Johanna Rosine, the daughter of a baker. Wagner not only survived his father who died of typhus only six months after his birth, but also The Battle of Nations at Leipzig.

Shortly after her husband’s demise, Johanna Rosine began a relationship with his friend Ludwig Geyer, an actor, playwright and painter who, until his death in 1921, brought up his stepson, Richard, as if he were his own. He might as well have been: until he was 14, Wagner carried the name Wilhelm Richard Geyer, as he believed Ludwig Geyer to be his biological father – in fact, the truth of Wagner’s paternity remains unknown to this day.

Geyer sparked Wagner’s love for the theatre, none other than the great composer Carl Maria von Weber and his opera Der Freischütz, his desire to become a composer. After listening to a recital of the 9th Symphony at the age of15, Wagner knew whom he had to measure up to: Beethoven became his idol, and until his death, Beethoven’s works were a main part of his repertoire as a conductor.

In 1831 Wagner began his music studies at the University of Leipzig and it was around that time that he began to compose his first opera, for which he also wrote the libretto — an unusual approach for an opera composer that Wagner maintained his entire life, for he believed that the revolution of opera had to occur on a broader level -- through its content, its form, its music and its language. To broaden the horizon of opera, Wagner sensed was his calling.

“Wagner wanted to do everything differently […] He wanted to cast a spell on people with a unique, extraordinary construct of text and music, a myth enchantment rich in symbols,” according to author Wolfram Goertz. Wagner’s great-granddaughter and the co-director of the Bayreuth Festival, Katharina Wagner, expressed this vision in a recent interview: “Wagner’s work is all about the basic elements of human existence and basic emotions such as jealousy, power, love, and hatred. Naturally these are things that will remain relevant as long as humans exist.” It is not without reason that Wagner wraps these elemental patterns of human and political conflict in mythical garments — Germanic myth in particular.

Wagner’s strive for reformation was not only limited to the realm of art. Like no other great artist of the 19th century, with the exception of Heinrich Heine, he sought interaction with the politically radical theorists of his time, most notably with the musician August Röckel and the Russian anarchist and revolutionary Michail Bakunin. Wagner’s political involvement, which was spurred by democratic and early Socialist thinking, and led him to the warpath during the May-Revolution in Dresden in 1849, was filled with resentment towards all the forces he believed to be the causes of social grievance: industrial modernism, capitalism, monarchism and, last but not least, Jewry.

“Wagner, like his meliorist brothers-in-arms, yearned for a new golden age, an idyllic world modeled on and illuminated by traditional German values,” Barry Millington states in his Wagner biography. In Wagner’s opinion, “German” art was the most effective weapon against modernity, and Jewry the biggest enemy of German art.

Anti-Semitism was a cultural code, as the Israeli historian Shulamit Volkov noted fittingly, a code that sourced from political passion and developed into a fundamental part of an entire culture. If one takes a closer look at the lives and works of the protagonists who played an integral role in shaping these codes, one will see how formative the years of the civil revolution of 1848 were for them, and how devastating its failure, which in Wagner’s case culminated in a multitude of art theoretical and political essays, of which Das Judentum in der Musik (Judaism in Music) from 1850 became his most famous. One of the central ideas of this detestable pamphlet was that the Jew is unable to produce original art work and therefore only capable of imitation. Artists like Heinrich Heine, Giacomo Meyerbeer and Felix Mendelssohn — whose great masterpieces paradoxically influenced Wagner — served him as a prime example.

It was no coincidence that the Wagners and Hitler crossed paths eventually. Richard’s daughter-in-law, Winifred Wagner, in particular, was a National Socialist of the first hour, who kept faith with her “Führer” even after 1945. Vice versa, Hitler developed a deep love and fascination for Wagner’s operas as an adolescent. He read every biography there was to read on the composer and knew Lohnegrin and Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg by heart. When he visited the Villa Wahnfried in Bayreuth for the first time (the famous residence of the Wagner family until its transformation into a museum in 1976), he was “very moved” at the sight of Wagner’s music room with the master’s grand piano, as Winifred recalled.

From that day on, the agitator and the Wagners developed a familial relationship and Hitler became a regular guest of honor at the annual Bayreuth Festival, which he put back on its feet financially. Over the years this alliance cooled off, not least because Winifred’s children didn’t want anything to do with the shame that not only haunts the green hills of Bayreuth until this day, but also the legacy of a brilliant composer.

“The reception of Wagner spawned plenty of monstrosities, no doubt about that, and who wants to remain angry will continue to speak of Wagner’s Hitler instead of Hitler’s Wagner,” writes Christine Lemke-Matwey on the occasion of Wagner’s sesquicentennial. That it is wrong to reduce Wagner’s legacy to his repugnant political beliefs was just recently proven by the visitors of the latest Tannhäuser staging at the Rheinoper in Düsseldorf. The director Burkhard Kosminski portrayed the eponymous hero as a Nazi, the Venus Mountain — for Wagner the place of hedonistic love — as the showplace of a brutal shooting scene. During the premiere in May the audience reacted with indignation and boos — some even left the hall. Düsseldorf’s Jewish Community criticized the show as tasteless.

“Wagner was without a doubt a glowing anti-Semite,” commented their director, Michael Szentei-Heise, “but it is not legitimate to throw that at the composer’s face in such a way […] Wagner had nothing to do with the Holocaust.” The vexing production was practically dropped shortly after. The opera will only be performed as a concert from now on, the Rheinoper announced.

Despite the controversies, we cannot separate Wagner into good and evil. Both are amalgamated in his persona as well as his work. Recognizing Wagner is therefore not a question of only like or dislike. He remains a powerhouse, albeit a controversial one, in the world of European classical music.

Author Bio:

Karolina Swasey is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.

Photos: Wikipedia Commons; Yngve Nielsen (Flickr); Brucke Osteuropa (Wikimedia, Creative Commons).