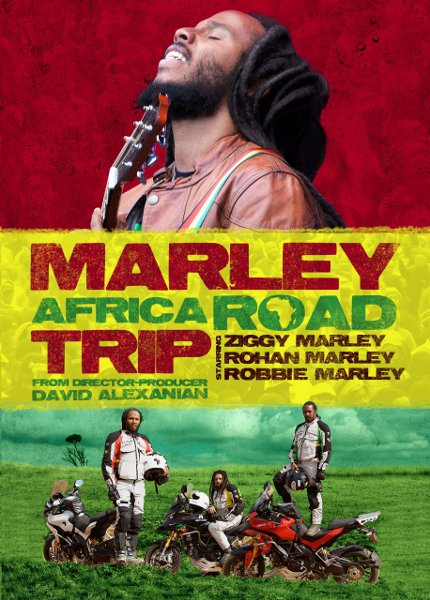

Documentary Follows Bob Marley’s Sons on an ‘Africa Road Trip’

Twenty years before Ziggy Marley began his “Africa road trip” and corresponding concert during the 2010 South African World Cup, his father, Bob Marley, performed in Zimbabwe to commemorate that country’s independence from British rule. The senior Marley played songs of freedom and African unity—intended for the people of Zimbabwe—to British royalty and Zimbabwe’s political dignitaries. The incongruence of that performance may have been impressed upon a young Ziggy Marley who was in attendance that night. Although the African political landscape has changed, the social dynamic of the continent is as confused now as it was in the years approaching the Zimbabwe concert. It may be for this reason that Ziggy Marley’s songs of freedom and African unity, like his father’s two decades prior, seemed to fall on deaf ears.

Bob Marley today is a product of pop culture bastardization. The impact of his music has been reduced to the two-dimensional, an image printed on T-shirts or plastered on dorm room walls. I may be generalizing. But anyone who has visited the campus of a California university is right to doubt whether those in the hacky-sack circle are true believers, genuine Rastafarians. “Imposter-farians” seems to be a more appropriate description. In the face of the proliferation of Bob Marley the image and product, a documentary following his sons’ experiences in Africa provides an opportunity to edify a generation still learning his music and dispel the prevailing cliché. Marley Africa Road Trip, directed by David Alexanian, begins with that very intention. The film, however, is ineffective.

Marley Africa Road Trip does not actually consist of a road trip. The Marleys’ excursions, which almost always find them returning to their luxury hotel by nightfall, fail to develop the organic sense of journey or adventure requisite for a road trip. They travel through the outskirts of Johannesburg on motorcycles provided to them by Ducati, presumably one of the film’s collaborators. Escorted by a camera crew, those bright and shiny motorcycles contrast the dirt roads which usher their arrival. They enter South African townships with engines revving, hardly a humble introduction to the people with whom they hope to connect. While following the Marleys’ travels through the outskirts of Johannesburg, the film often stresses South Africa’s tenuous infrastructure, poverty and need for social change. These concerns certainly exist. To itemize them, however, as the Marleys and Mr. Alexanian do throughout the film, simply repeats the maudlin narratives of Africa—which serves only those with a view from afar—and ignores the resiliency of its people.

The film is billed as documentary but plays much more like reality television. The DVD package is divided into five episodes. Fans of the Marleys solely as musicians can skip to the finale, which consists of live footage from the Ziggy Marley concert in Soweto in 2010. You’ll be spared much of the preceding footage which bears all the exasperating markers of reality television, the funhouse reflection of the human experience enacted by those fully aware that their lives are being recorded. The distortion is less obvious during Ziggy’s unguarded moments. We find the righteousness of his music drawn from what seems a genuine idealism, specifically an appetite for social justice. This was also his father’s cause and in moments of uncertainty, Ziggy confides in the senior Marley’s spirit. Despite Bob Marley’s passing decades ago, the relationship between son and father throughout the film appears much stronger than the relationship between the Marley brothers. It becomes obvious early on that fraternity is surpassed by their disparate pasts.

They may set out each morning together and end up at the same destination, but the distance between the three Marley brothers is evident. Robbie Marley says no more than a few lines throughout the film. They refer to him as “Ninja,” reference to his motorcycle stunt riding abilities. Other than a few unrelated introductory clips, we don’t see much of his trick riding ability. His role is further marginalized in the film by his reluctance to be depicted on camera

Rohan Marley is deemed the entrepreneur. He has utilized the Marley name in establishing a successful coffee company. During the shooting, he tours the grounds of a South African coffee grower to evaluate the potential for expansion of his business. Rohan frames his company as an inevitable result of his family’s relationship to the soil. His business dealings, however, seem to contrast the intentions of the film: Rohan considers the viability of expanding his operation into Africa while Ziggy endeavors to put on a free concert for the down and out in Soweto. The capitalist in Rohan reflects the bifurcation of his father’s legacy. The branch consisting of Bob Marley the product and image is steadily separating itself from the source, Bob Marley the revolutionary, poet and idealist.

Marley Africa Road Trip barely skims the surface of Africa. The concert in Soweto, despite a few initial setbacks, ultimately proceeds without complications. Ziggy plays his father’s music flawlessly. If not a performance to encourage social change, Ziggy provided at least an adequate tribute to his father’s concert in Zimbabwe two decades prior. But of the 299 minutes of total running time in this movie, that adequacy can be applied to only a half hour or so of concert footage. The DVD synopsis states that Marley Africa Road Trip is “sure to be considered one of the great soundtracks.” That’s quite a stretch, but it’s still closer to the truth than Marley Africa Road Trip being considered one of the great, or even tolerable, documentaries.

Author Bio:

Steven Chandler is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.